Navy's New Constellation Class Frigate Is A Mess

The U.S. Navy's future Constellation class frigates could see their top speeds cut back to help mitigate unexpected growth in their overall weight. The Navy and shipbuilder Fincantieri Marinette Marine otherwise continue to grapple with the impacts of major changes in the ship's configuration compared to its Franco-Italian Fregata Europea Multi-Missione (FREMM) parent design. The entire purpose of basing the Constellations on an existing in-production frigate was to help reduce costs, delivery times, and risk, but they have shaped up to be larger, heavier, and now years behind schedule.

New details about weight growth, design instability, and other issues with the Constellation class frigate came in a report the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), a Congressional watchdog, published yesterday. Just last week, the Navy awarded a new contract to Fincantieri Marinette Marine, valued at just over $1.04 billion, for another two of the frigates. The service now has six Constellations on order, the first of which is currently under construction.

At the same time, the Navy has already confirmed that it now the first Constellation class frigate may not be delivered until 2029, three years behind schedule. This would also be around nine years after Fincantieri Marinette Marine received its initial contract for the frigates and some seven years after the start of construction of the USS Constellation.

As another data point about the current state of the initial Constellation class ship, "the Navy reported that, as of September 2023, the shipbuilder had completed construction of only 3.6 percent of the lead ship as compared to the 35.5 percent it was scheduled to have completed by that point," GAO reported.

"A complicating factor in assessing new dates for frigate deliveries is the shipbuilder’s October 2023 reporting of unplanned weight growth in the frigate design – an increase of over 10 percent above the shipbuilder’s June 2020 weight estimate," according to GAO. "The Navy’s decision to approve construction with incomplete elements of the ship design – including information gaps related to structural, piping, ventilation, and other systems – and the underestimation of adapting a foreign design to meet Navy requirements have driven this weight growth."

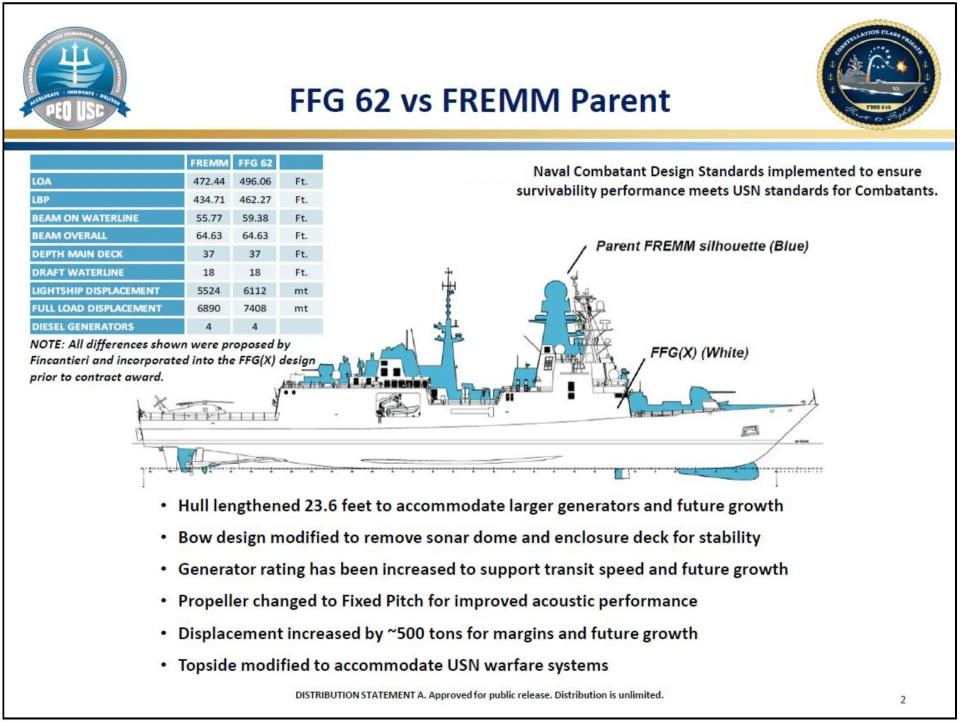

It's worth noting here that by 2021, it had already become clear that the Constellation class design would be 24 feet longer and just over three and a half feet wider along the waterline compared to its FREMM parent. In addition, the Navy said at that time that the Constellation's displacement had grown by around 500 tons "for margins and future growth."

Whether or not the unplanned weight growth GAO has now disclosed is within the Navy's previously stated increased weight margin is unclear and The War Zone has reached out to Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA) for more information.

Regardless, "resolving this weight growth adds another dimension to the shipbuilder’s ongoing design activities, further diminishing the predictability of these already schedule-challenged efforts," per GAO's report. "The Navy disclosed to us in April 2024 that it is considering a reduction in the frigate’s speed requirement as one potential way, among others, to resolve the weight growth affecting the ship’s design."

To date, the Navy does not appear to have disclosed its speed requirements for the Constellation class, but the ships are reportedly expected to be able to sustain a cruising speed of at least 26 knots. This is in line with the stated "max continuous speed" of the Italian Bergamini class subvariant of the FREMM design, which is in excess of 27 knots, according to Fincantieri. A speed of at least around 30 knots would be necessary for keeping up with Navy carrier strike groups.

The War Zone has also reached out to NAVSEA for more details on other options being considered to help resolve and/or mitigate the weight growth issues.

On top of all this, the construction of the USS Constellation had been proceeding, at least as of last year, without a finalized design.

"Design stability is achieved upon completion of a basic and functional design in a 3D model, using reliable vendor-furnished information incorporated to support an understanding of final system design, among other things," according to GAO. However, "the Navy began frigate construction in August 2022 with an incomplete functional design, counter to leading ship design practices."

As of August 2023, a year after work started, the Constellation's functional design and 3D model were assessed to be 92 and 84 percent complete, respectively, per GAO.

Overall, the design commonality between the Constellation and FREMM may now be as low as 15 percent, according to USNI News. GAO's new report says that this includes substantial changes to the combined diesel-electric and gas turbine propulsion system and associated machinery control systems, which has "increased cost and introduced integration risks, according to shipbuilder representatives."

In addition, "the Navy adapted the parent design to accommodate... [new U.S.-specific mission] systems and meet Navy habitability and survivability requirements," GAO's report notes. The War Zone did a deep dive into the Constellation class' expected capabilities, focused on questions surrounding the size of its Mk 41 Vertical Launch System (VLS) array, earlier this year, which you can find here.

Beyond all this, "unplanned weight growth during ship construction can compromise ship capabilities in the short term (i.e., upon delivery of the ship to the fleet) and in the long term, as the fleet seeks to alter and improve initial capabilities over the planned decades-long service life of the ship," GAO has warned.

Having extra margins for growth is critical. There has already been talk about integrating directed energy and other weapons, as well as other capabilities, on the Constellations down the road. Otherwise, it will be far more challenging economically to keep the ships operationally relevant over their service lives.

GAO also cited the Navy's previous experience with the Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) program. The construction of the initial examples of both LCS subclasses deliberately began without a firm design, a process commonly known as concurrency. This resulted in the first two examples of both the Independence and Freedom class designs being substantially different from the ships that followed. This, in turn, led to them quickly being relegated to training and test roles. The USS Freedom (LCS-1), the USS Independence (LCS-2), and the USS Coronado (LCS-4) have all now been decommissioned. The oldest of those ships, Freedom, had been in service for just 13 years. The Navy is now moving to retire even more LCSs from both subclasses in the coming years.

The Navy's decision to acquire the Constellation class frigates has been seen as a major rebuke of the LCS program and its persistent failure to live up to expectations. As already noted, using an established in-production parent design, a core requirement of what was originally known as the FFG(X) program, was supposed to help limit cost growth and other technical and schedule risks.

For its part, in the face of increasing criticism of the progress, or lack thereof, in the development and construction of the Constellation class frigates even before the release of the GAO's new report, the Navy has largely placed the blame on workforce issues at the shipbuilder. There has been talk about bringing in a second shipyard to help with the production of the Constellations.

"In the case of the [Constellation class] frigate, quite frankly, it's a... recruiting and retention problem in Wisconsin," Secretary of the Navy Carlos Del Toro told members of the Senate Armed Services Committee at a hearing earlier this month.

However, Mississippi Senator Roger Wicker, the ranking Republican on the Committee, had already disputed this in his opening remarks at that same hearing.

"The Constellation class frigate will be three years late and will take nearly 10 years to deliver the lead ship. This is largely because the Navy cannot keep its requirements steady. Almost 70 percent of the requirements have changed since the Navy signed a contract," Wicker said. "So the outcome that we see today is no surprise. This is not an example of the industry underperforming. This is senior officials unable to manage a program. This is acquisition malpractice and a terrible waste of time and resources."

Wicker's comments are well in line with what the GAO has now reported.

How and when the Navy, together with Fincantieri Marinette Marine, will be able to finally stabilize the Constellation class' weight and other design elements, and whether the ship's top speed takes a hit as a result, very much remains to be seen.

Contact the author: [email protected]