Meet AdVon, the AI-Powered Content Monster Infecting the Media Industry

A few years back, a writer in a developing country started doing contract work for a company called AdVon Commerce, getting a few pennies per word to write online product reviews.

But the writer — who like other AdVon sources interviewed for this story spoke on condition of anonymity — recalls that the gig's responsibilities soon shifted. Instead of writing, they were now tasked with polishing drafts generated using an AI system the company was developing, internally dubbed MEL.

"They started using AI for content generation," the former AdVon worker told us, "and paid even less than what they were paying before."

The former writer was asked to leave detailed notes on MEL's work — feedback they believe was used to fine-tune the AI which would eventually replace their role entirely.

The situation continued until MEL "got trained enough to write on its own," they said. "Soon after, we were released from our positions as writers."

"I suffered quite a lot," they added. "They were exploitative."

We first heard of AdVon last year, after staff at Gannett noticed product reviews getting published on the website of USA Today with bylines that didn't seem to correspond to real people. The articles were stilted and formulaic, leading the writers' union to accuse them of being "shoddy AI."

When Gannett blamed the strange articles on AdVon, we started digging. We soon found AdVon had been running a similar operation at the magazine Sports Illustrated, publishing product reviews using bylines of fake writers with fictional biographies and AI-generated profile pictures. The response was explosive: the magazine's union wrote that it was "horrified," while its publisher cut ties with AdVon and subsequently fired its CEO before losing the rights to Sports Illustrated entirely.

AdVon disputed neither that the bylines were fake nor that their profile pictures had been generated using AI. But it insisted, at both USA Today and Sports Illustrated, that the actual articles had been written by actual humans.

We wanted to learn more. What kind of a company creates fake authors for a famous newspaper or magazine and operates them like sock puppets? Did AdVon have other clients? And was it being truthful that the reviews had been created by humans rather than AI?

So we spent months investigating AdVon by interviewing its current and former workers, obtaining its internal documentation, and searching for more of its fake writers across the web.

What we found should alarm anyone who cares about a trustworthy and ethical media industry. Basically, AdVon engages in what Google calls "site reputation abuse": it strikes deals with publishers in which it provides huge numbers of extremely low-quality product reviews — often for surprisingly prominent publications — intended to pull in traffic from people Googling things like "best ab roller." The idea seems to be that these visitors will be fooled into thinking the recommendations were made by the publication's actual journalists and click one of the articles' affiliate links, kicking back a little money if they make a purchase.

It's a practice that blurs the line between journalism and advertising to the breaking point, makes the web worse for everybody, and renders basic questions like "is this writer a real person?" fuzzier and fuzzier.

And sources say yes, the content is frequently produced using AI.

"It's completely AI-generated at this point," a different AdVon insider told us, explaining that staff essentially "generate an AI-written article and polish it."

Behind the scenes, AdVon responded to our reporting with a fusillade of denials and legal threats. At one point, its attorneys gave us seven days to issue a retraction on our Sports Illustrated story to avoid "protracted litigation" — but after the deadline came and went, no legal action materialized.

"Advon [sic] is proud to use AI responsibly in combination with human writers and editors for partners who want increased productivity and accuracy in their commerce departments," the company wrote in a statement. "Sport Illustrated [sic] was not one of those AI partners. We always give explicit ethical control to our publishing partners to decide the level of AI tooling they want in the content creation process — including none if they so choose, which has been part of our business since founding."

It's possible this is true. Maybe AdVon used AI-generated headshots to create fictional writers and stopped there, only using the fake authors' bylines to publish content produced by flesh-and-blood humans.

But looking at the evidence, it's hard to believe.

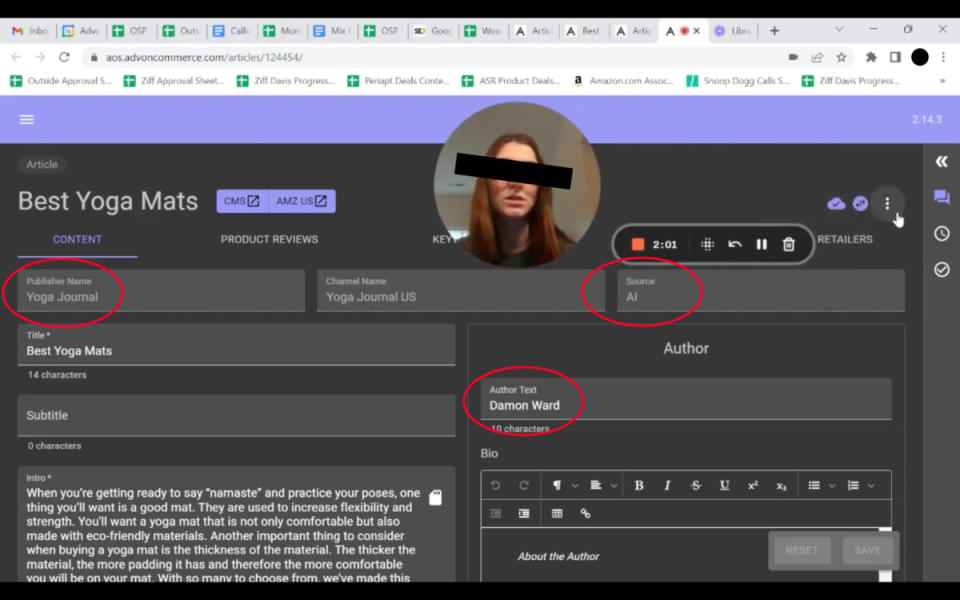

Consider a training video provided to us by an insider at the company. In it, an AdVon manager shares her screen, showing a content management system hosted on the company's website, AdVonCommerce.com. In the video, the manager uses the CMS to open and edit a list of product recommendations, titled "Best Yoga Mats" and bylined by one of the fake Sports Illustrated writers, Damon Ward.

The article's "source," according to a field in the CMS, is "AI."

Like the other fake writers at Sports Illustrated, we found Ward's profile picture listed for sale on a site that sells AI-generated headshots, where he's described as "joyful black young-adult male with short black hair and brown eyes."

Often, we found, AdVon would reuse a single fake writer across multiple publications. In the training video, for instance, the Damon Ward article the manager edits in the CMS wasn't for Sports Illustrated, but for another outlet, Yoga Journal.

A spokesperson for Yoga Journal owner Outside Inc — the portfolio of which also includes the acclaimed magazine Outside — confirmed to us that AdVon had previously published content for several of its titles including Yoga Journal, Backpacker, and Clean Eating. But it ended up terminating the relationship in 2023, the spokesperson told us, due to the poor quality of AdVon's work.

In spite of the article being labeled as "AI" in AdVon's CMS, the Outside Inc spokesperson said the company had no knowledge of the use of AI by AdVon — seemingly contradicting AdVon’s claim that automation was only used with publishers' knowledge.

When we asked AdVon about that discrepancy, it didn't respond.

***

As we traced AdVon's web of fake bylines like Damon Ward, it quickly became clear that the company had been publishing content well beyond Sports Illustrated and USA Today.

We found the company's phony authors and their work everywhere from celebrity gossip outlets like Hollywood Life and Us Weekly to venerable newspapers like the Los Angeles Times, the latter of which also told us that it had broken off its relationship with AdVon after finding its work unsatisfactory.

And after we sent detailed questions about this story to McClatchy, a large publisher of regional newspapers, it also ended its relationship with AdVon and deleted hundreds of its pieces — bylined by at least 14 fake authors — from more than 20 of its papers, ranging from the Miami Herald to the Sacramento Bee.

"As a result of our review we have begun removing Advon [sic] content from our sites," a McClatchy spokesperson told us in a statement, "and are in the process of terminating our business relationship."

[Do you know of other publications where AdVon content has appeared? Email us at [email protected] — we can keep you anonymous.]

AdVon's reach may be even larger. An earlier, archived version of its site bragged that its publishing clients included the Ziff Davis titles PC Magazine, Mashable and AskMen (Ziff Davis didn't respond to questions about this story) as well as Hearst's Good Housekeeping (Hearst didn't respond to questions either) and IAC's Dotdash Meredith publications People, Parents, Food & Wine, InStyle, Real Simple, Travel + Leisure, Better Homes & Gardens and Southern Living (IAC confirmed that Meredith had a relationship with AdVon prior to its 2021 acquisition by Dotdash, but said it'd since ended the partnership.)

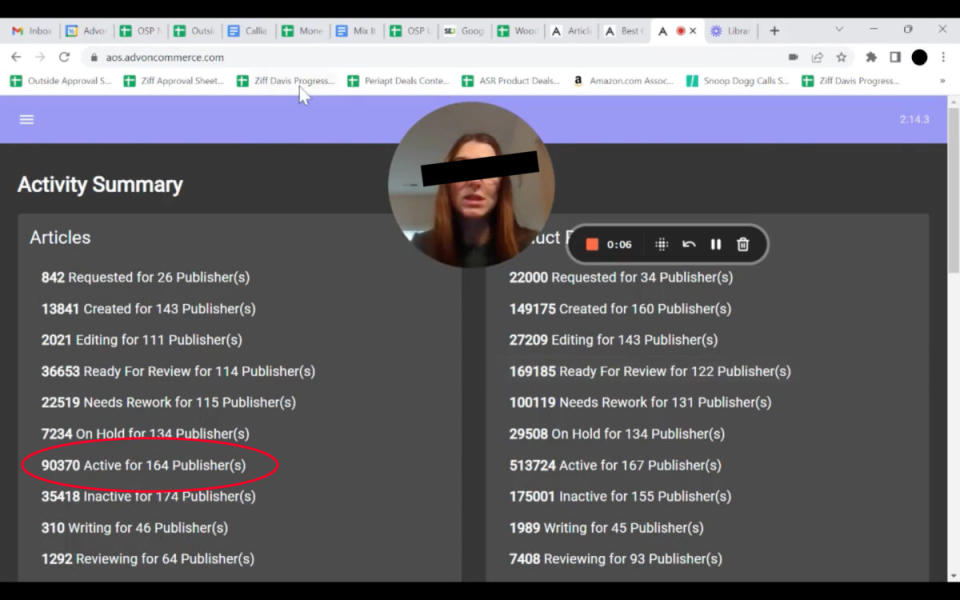

The archived version of AdVon's site — from which it removed the publisher list following the outcry over its fake writers — also claimed that it worked with "many more" clients. This may well be true: the video of AdVon's CMS in action appears to show that the company had produced tens of thousands of articles for more than 150 publishers.

In fact, we learned while reporting, AdVon even has business ties to Futurism's parent company, Recurrent Ventures — which you can read more about in the disclosure at the bottom of this piece — though it's never had any involvement with Futurism itself.

Despite those ties, we continued investigating AdVon, and experienced zero interference from anyone at Recurrent. That said, AdVon's cofounder responded to questions about this story by pointedly informing us of his business and personal connections with Recurrent's CEO and the executive chairman of Recurrent's board, in what felt like an effort to hamper our reporting by implying access to a corridor of power over our jobs. As you're about to read: didn't work.

***

Another AdVon training video we obtained shows how the AI sausage is made.

In it, the same manager demonstrates how to use the company's MEL AI software to generate an entire review. Strikingly, the only text the manager actually inputs herself is the headline — "Best Bicycles for Kids" — and a series of links to Amazon products.

Then the AI generates every single word of the article — "riding a bike is a right of passage that every child should experience," MEL advises, adding that biking teaches children important "life skills" like "how to balance and how to be responsible for their actions" — as the manager clicks buttons like "Generate Intro Paragraph" and "Generate Product Awards."

The result is that MEL's work is often stilted and vague. At one point in the video, the manager enters an Amazon link to a vacuum cleaner and clicks "Generate Product Pros." MEL spits out a list of bona fides that are true of any desirable vacuum, like "picks up a lot of dirt and debris" and "lightweight and maneuverable." But MEL also sometimes contradicts itself: moments later, when the manager clicks "Generate Product Cons," the bot suggests that the same "lightweight and maneuverable" vacuum is now "top heavy and can feel unwieldy at first."

If an output doesn't make sense, the manager explains in the video, workers should simply generate a new version.

"Just keep regenerating," she says, "until you’ve got something you can work with."

By the end of the video, the manager has produced an article identical in structure to the AdVon content we found at Sports Illustrated and other AdVon-affiliated publications: an intro, followed by a string of generically-described products with affiliate links to Amazon, a "buying guide" packed with SEO keywords, and finally an FAQ.

"Our goal is not for it to sound like a robot has written it," the manager instructs, "but that a writer, a human writer, has written it."

That's a tall order, AdVon insiders say, because the AI's outputs are frequently incomprehensible.

"I'm editing this stuff where there's no quality control," one former AdVon worker griped about the AI. "I'm just editing garbage."

The quality of AdVon's work is often so dismal that it's jarring to see it published by respected publications like USA Today, Sports Illustrated or McClatchy's many local newspapers. Its reviews are packed with filler and truisms, and sometimes include bizarre mistakes that make it difficult to believe a human ever seriously reviewed the draft before publication.

Take a piece AdVon published in Washington's Tacoma News Tribune. The review is for a weight lifting belt, which is a fitness device you strap on outside your clothes to offer back and core support when lifting weights at the gym. But when the author — who calls themselves a "belt expert" in the piece — arrives at the SEO-laden "buying guide" section, the review abruptly switches to talking about regular belts for clothing, advising that their "primary purpose is to hold up your trousers or jeans" and that they serve "as an important part of your overall outfit, adding style and a personal touch."

Even stranger is a separate AdVon review for lifting belts, by the same author and published in the same newspaper, that makes exactly the same weird mistake. At first, it says a lifting belt "provides the necessary back support to prevent injuries and enhance your lifting capabilities" — before again veering into the world of fashion with no explanation, musing that "Gucci, Hermes, and Salvatore Ferragamo are well-known for their high-quality belts."

Or consider an AdVon review of a microwave oven published in South Carolina's Rock Hill Herald, which made a similarly peculiar error. The first portion of the article is indeed about microwaves, but then inexplicably changes gears to conventional ovens, with no explanation for the shift.

In the FAQ — remember, the piece is titled "Amazon Basics Microwave Review" — it even assures readers that "yes, you can use aluminum foil in your oven."

If that wasn't bizarre enough, four other reviews of different microwaves — all for the same newspaper and credited to the same author — make exactly the same perplexing mistake: partway through, they each switch to discussing regular ovens with no explanation, as though a prompt to an AI had been insufficiently precise.

All five of the microwave reviews include an FAQ entry saying it's okay to put aluminum foil in your prospective new purchase.

***

Once they were done working on an article for AdVon, insiders say, it was time to slap the name of a fake writer onto it.

"Let's say if I was editing an article about a basketball product, that would have a different 'writer' than maybe like a yard games product," said one AdVon source. "They had all of those discrete bios written up already, and they had the pictures as well."

Because this person grew up reading Sports Illustrated, producing content for the publication in this way yielded mixed emotions.

"I'm not, like, editing for Sports Illustrated," the AdVon source said, "but like, editing for articles on Sports Illustrated. That's kinda cool." But, they added, "it was weird whenever I got to the bottom, and I would have to, you know, add in that [nonexistent writer's] fake description."

After the Gannett staff called out AdVon's work at USA Today — allegations that garnered scrutiny everywhere from the Washington Post to the New York Times — the fictional names on the company's reviews started disappearing. They were replaced with the names of people who did seem to be real — and who, we noticed, frequently had close personal ties to AdVon's CEO, a serial media entrepreneur named Ben Faw.

Take the byline of Julia Yoo. Yoo's name started to appear on articles — including the ones about microwave ovens and aluminum foil — that had previously been attributed to a seemingly fake writer named Breanna Miller, whose reviews had run at publications including California's Modesto Bee, Texas' Fort Worth Star-Telegram, and celebrity news site Hollywood Life. On some of the pieces, a strange correction appeared: "This article was updated to correct the author’s byline and contact information."

Compared to AdVon's other production workers, who are often either recent college graduates or contractors in the developing world, Yoo seems wildly overqualified. Her LinkedIn page boasts a business degree from MIT, a director position at Autodesk, and even a stint as an economic consultant to the White House during the Obama administration.

But there's something about Yoo's byline that rings hollow. According to a wedding registry and a Harvard donor web page, Ben Faw — the CEO of AdVon — is married to someone named Julia Yoo.

In an emailed message in response to questions, Yoo said she had used a "pen-name [sic] to protect my privacy" in her reviews. Asked if she was married to Ben Faw, she didn't reply.

Or consider Denise Faw, whose name started to appear on articles — including those that confused lifting belts with Gucci belts — that had previously been attributed to a seemingly fake writer named Gary Lecompte at California's Merced Sun-Star, Georgia's Ledger-Enquirer, and Missouri's Kansas City Star.

Denise Faw, you may notice, shares a last name with Ben Faw, the CEO of AdVon who's married to Julia Yoo. Denise didn't reply to a request for comment, but according to a 1993 article in the Greensboro News & Record, Ben Faw — then a third grader who garnered the coverage by earning a "God and Me" pin as a Cub Scout — has a mother whose first name is Denise. We also reviewed an online invite for Ben Faw's birthday party, to which a Denise Faw responded that she couldn’t make it, signing off on behalf of "Mom and Dad."

Given how Denise's and Julia's names suddenly appeared on articles by fake AdVon writers, it's hard not to wonder whether they actually wrote the pieces — or if AdVon simply started slapping their names onto AI-generated product reviews to deflect criticism after the outcry over its fake writers.

Asked about its relationship to Julia Yoo and Denise Faw, and whether they'd actually written the articles later attributed to them, AdVon didn't respond.

***

If AdVon is using AI to produce product reviews, it raises an interesting question: do its human employees actually try the products being recommended?

"No," laughed one AdVon source. "No. One hundred percent no."

"I didn't touch a single one," another recalled.

In fact, it seems that many products only appear in AdVon's reviews in the first place because their sellers paid AdVon for the publicity.

That's because the founding duo behind AdVon, CEO Ben Faw and president Eric Spurling, also quietly operate another company called SellerRocket, which charges the sellers of Amazon products for coverage in the same publications where AdVon publishes product reviews.

In a series of promotional YouTube videos, SellerRocket employees lay out how the scheme works in strikingly candid terms.

"We have what's called a curation fee, which is only charged when an article goes live — so SellerRocket advocates for your brands and if we can't get an article live, you would never pay a dime," said a former SellerRocket general manager named Eric Suddarth during one such video. "But if the articles do go live, you'd be charged a curation fee." After that, he said, clients are charged recurring fees every month.

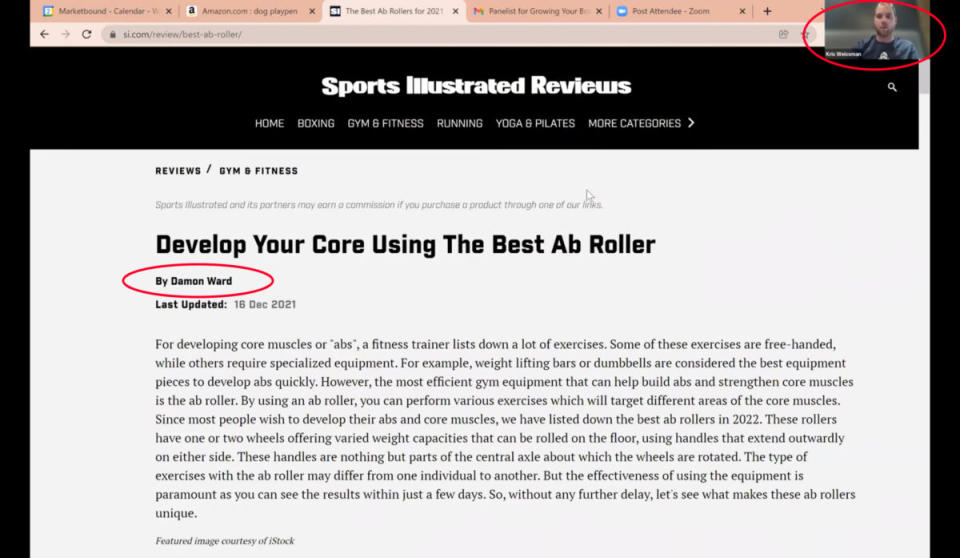

In another video, SellerRocket's general manager at the time Kris Weissman shares his screen to demonstrate how searching "best ab roller" on Google will lead to an article on "one of our publishers here, Sports Illustrated." He clicks the link on Google and it pulls up a Sports Illustrated product review by Damon Ward, the same fake writer whose Yoga Journal article the AdVon training video showed as being sourced via AI.

People searching Google to buy a product, Weissman explains, are easily swayed by reviews in authoritative publications.

"If they came across your product featured in the editorial, they know it's a third-party publisher that's validating the legitimacy of the product," he says, with Ward's ab roller recommendations on Sports Illustrated still visible on his screen, "and they're going to gravitate more towards that versus maybe a typical consumer."

Paying for this coverage can be invaluable for publicizing a new product, Weissman explains in another video featuring the same ab roller article.

"If you have a newer product that you're looking to launch, get those reviews," says Weissman, now a vice president at the company. "We usually recommend, have it out for at least a month or so, then you want to try to highlight it and get some traction to it, let us know. We can get you into one of these Google search articles as well."

In yet another video, a SellerRocket client gushes on behalf of the service.

"Oh my gosh, that Sports Illustrated article is just, man it's driving some conversions," she says.

AdVon and SellerRocket are so intertwined that AdVon's CMS includes a "cute little rocket icon" next to SellerRocket's clients' products, one former AdVon worker recalled, adding that SellerRocket clients "always took priority."

In fact, in the training video in which the AdVon manager pulls up the article bylined by the fake Sports Illustrated writer Damon Ward, you can see links that say "Seller Rocket [sic] Throughput" and "Seller Rocket [sic] Reports" in AdVon's CMS.

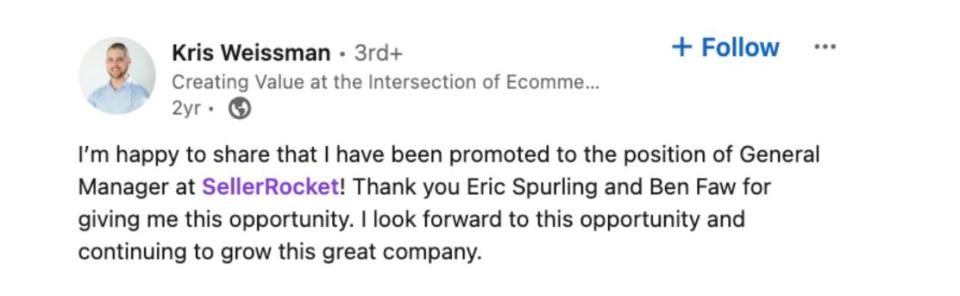

Neither Faw's nor Spurling's names appear anywhere on SellerRocket's website. But Weissman, in a LinkedIn post celebrating his promotion to general manager, thanked "Eric Spurling and Ben Faw for giving me this opportunity."

Asked about AdVon's relationship with SellerRocket — and whether it was ethical for the seller of a product to pay for placement in a "product guide" or "product review" sans disclosure — AdVon had no reply.

[Do you know more about AdVon's work with SellerRocket? Email us at [email protected]. We can keep you anonymous.]

***

Ben Faw — the CEO of AdVon whose mom and wife's names were added to so many of its articles — maintains a polished LinkedIn page describing an illustrious career: a stint in the US Army, degrees from West Point and Harvard Business School, and positions at companies ranging from Tesla to LinkedIn itself.

While still working at LinkedIn, Faw moved into the world of online product recommendations by starting a company called BestReviews in 2014. The business model at BestReviews was simple: publish large numbers of product reviews, each loaded with affiliate links that provide revenue when readers click through and buy stuff.

That's now a fairly standard way to make money in digital media. When done well — take the New York Times-owned Wirecutter or New York Magazine's The Strategist — it can be a win-win, providing valuable guidance to readers while funding media businesses producing quality editorial work.

A former colleague of Faw, however, recalled that he could be relentless in trying to squeeze more money out of lower-quality material. Though BestReviews' staff did the best job they could, the former coworker said, Faw pushed the site to be more of a "content farm" — one that ran large quantities of junky content by "terrible writers."

"He has total disdain for the consumer," the former colleague said, adding that Faw would seize on "any way he could do it fast and cheap to make himself more money. I mean, he just cared about revenue. That's all he cared about."

In 2018, Faw got a significant windfall when Tribune Publishing — then called Tronc, in a disastrous rebranding it later reversed, and also then the owner of the LA Times, where AdVon content was later published — acquired a majority stake in BestReviews for $66 million.

The next year, he left his executive position at BestReviews and founded AdVon.

When we first contacted Faw, he responded by repeatedly emphasizing personal and business connections to people high up at Futurism's parent company, writing in an email that he had "legal obligations with the predecessor entity to Recurrent Ventures" that "drastically reduce where all I [sic] or entities I am involved with can engage with Recurrent."

The next day, Faw followed up with another message that was even more blunt about his connections to the leadership at Futurism's parent company.

"Have a long-standing personal relationship with new [R]ecurrent [CEO] Andrew Perlman (realized / confirmed he became CEO today while catching up with [Recurrent Executive Chair] Mark Lieberman), and a financial arrangement with him as well," he cautioned us.

"Know the new Exec [C]hairman of [R]ecurrent (Mark Lieberman)," he added. "Have on-going [sic] financial ties with [R]ecurrent as both business actions and via related parties ownership of a stake in the company."

According to the former colleague of Faw, this isn't surprising behavior.

"He's a huge name-dropper," they said. "He will always try to pull that on you."

"Ben loved to brag about how he is 100 percent sure every journalist in the world is for sale, as long as you pay enough money," they added.

We checked in with Recurrent's leadership about what Faw told us. They acknowledged the business ties and provided the disclosure at the bottom of this story, but reaffirmed their commitment to editorial independence, and didn't interfere with our reporting in any way.

***

As our reporting progressed, AdVon's claims evolved.

When we first reached out to the company after the fake writers at Gannett emerged, its president Eric Spurling firmly denied that the company was using AI for any publisher clients.

"We use AI in a variety of retailer specific product offerings for our customers," he wrote. "That is a completely separate division from our publisher focused services, and an exciting / large part of our company that is and has been siloed apart," adding that "any editorial content efforts with publisher partners we have involved a staff of both full-time and non full-time writers and researchers who curate content and follow a strict policy that also involves using both counter plagiarism and counter-AI software on all content."

But after we alerted AdVon to the video we obtained of the manager using AI to generate an entire review guide, its story seemed to shift, acknowledging that AI was in the mix for at least some of its publishing clients.

"Advon [sic] has and continues to use AI responsibly in combination with human writers and editors for partners who want increased productivity and accuracy in their commerce departments," Spurling wrote in a "declaration" provided to us by one of the company's attorneys. "Sport Illustrated [sic] was never a publishing partner that requested or was provided content produced by Advon’s [sic] AI tools."

After this point, the only communications we received from AdVon were through a series of its attorneys. Though they didn't dispute that the Sports Illustrated authors were fake, nor that their profile pictures had been generated using AI, the lawyers pushed back strongly against the idea that the Sports Illustrated articles’ text had been produced using AI.

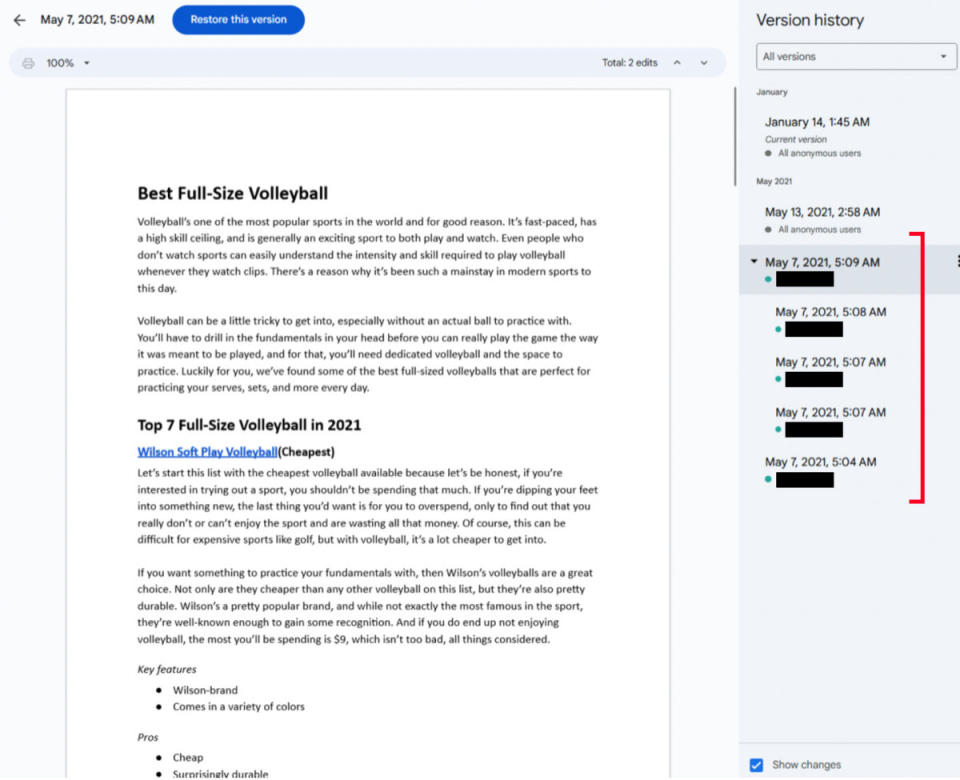

As evidence, one of AdVon's attorneys provided screenshots of what he said were the Google Docs edit histories of several AdVon articles.

In theory, these edit histories could be compelling evidence against the notion that the articles were generated using AI. If they showed drafts being typed out over a reasonable period of time, it'd make a strong case that a human writer had written them instead of pasting in an entire piece generated by AI.

But that's not what the screenshots show. For example, one of the edit histories is for a Sports Illustrated review of various volleyballs. The article is about 2,200 words long, but the edit history shows its author producing the whole draft in just five minutes, between 5:04 am and 5:09 am on the same morning.

Banging out 2,200 words in five minutes would require a typing speed of 440 words per minute, which is substantially faster than the current world record for speed typing, which stands at just 300 words per minute.

Another edit history provided by AdVon shows that the entire piece — "The Best Golf Mats to Help You Up Your Game" — was produced in just two minutes, between 7:16 am and 7:18 am on the same morning.

Asked how a human writer could have created the articles so quickly, AdVon's attorney proffered a new suggestion: they had been copied and pasted from somewhere else, writing that "its [sic] common practice for a writer to draft an article in a particular word processor (MS Word, WordPerfect) and import (cut and paste) the text into another word processor (such as Google Docs) or CMS."

Of course, it's also possible to generate an article using AI and then paste it into Google Docs.

Asked whether it could provide the edit histories to the original drafts of the articles, AdVon didn't reply.

***

The company also insisted that MEL wasn’t operational until 2023.

"More important, Advon [sic] stands by its statement that all of the articles provided to Sports Illustrated were authored and edited by human writers," AdVon's attorney wrote. "Advon's [sic] MEL AI tool was not used in content processes until 2023."

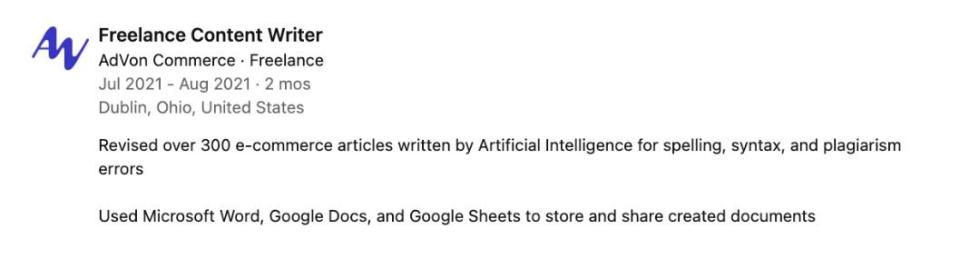

But it very much looks as though the company was using AI before then. For one thing, several of the company's current and former workers say on LinkedIn that they were working on AI content long before 2023.

One former AdVon freelancer recalled on LinkedIn that he "revised over 300 e-commerce articles written by Artificial Intelligence for spelling, syntax, and plagiarism errors" during a two-month period in 2021.

A former AdVon intern's LinkedIn profile recalls how she "edited AI-generated content to encourage machine learning and improve the automated product description writing process" the same year, in 2021.

And an AdVon machine learning engineer who started working for AdVon in 2021 also claims on LinkedIn to have "led the way in enhancing content with advanced AI like GPT-2, GPT-3, and GPT-4." (OpenAI released GPT-2 in 2019, GPT-3 in 2020 and GPT-4 in 2023.)

There's also the matter of that video where the AdVon employee opens an already-published article marked as "AI" in the company's CMS. The video was published in December 2022, before Spurling or AdVon's attorneys claimed the company had been using MEL.

Asked about the apparent discrepancies, AdVon had no reply.

***

When we asked AdVon whether it terminated any human writing staff as it made its AI shift, Spurling issued a vehement denial, declaring over email that "the basis" of our question was "not accurate."

"We work with and pay many freelance writers," he wrote.

Again, LinkedIn seems to dispute this claim. As of 2022, dozens of AdVon workers say on their profiles that they were writing for the company — but that figure declined to approximately 18 in 2023 and just five currently.

Asked to explain where the writers had gone, AdVon didn't reply.

AdVon insiders concur that the company let go of a large number of writers in its move to automate.

"They were like, alright, we're gonna roll out the AI writing," said another former AdVon worker, this one based in the United States. This source recalled that AdVon's instructions were "when you edit these, make sure you give really extensive feedback — be very detailed and in-depth about what the issues are so we can tweak it."

Like others, they said the work was frustrating due to the AI copy's incoherence. "The further you got down into the article, the blog, it just would not, like, make any sense at all," they continued, adding that the AI would repeat nonsensical phrases or SEO "buzzwords," or inexplicably launch into first-person anecdotes.

"The AI would use quote-unquote 'personal experience,'" they recalled, "and you're just like, 'where did they pull this from?'"

Watching vulnerable contractors in overseas countries get let go as the AI matured, the former worker said, was gutting.

"I remember when I was a kid, my dad got laid off," they said. "It was horrid — terrible. And I just think about that with [the AdVon writers] living overseas. I obviously don't know the rest of their situation, but that's scary no matter what your circumstances are. I just felt so bad."

***

It's hard to say where AdVon's prospects stand these days.

It seems to still have some clients. While publishers ranging from McClatchy to the LA Times told us they'd stopped working with AdVon altogether, others including USA Today, Hollywood Life and Us Weekly appear to still be publishing its work (neither Hollywood Life nor Us Weekly responded to requests for comment, while Gannett referred to the content as "arbitrage marketing efforts," saying they involved "buying search keywords and monetizing these clicks by preparing curated marketing landing pages to accommodate keyword buying campaigns.")

Lately, AdVon seems to be trying to rebrand as a creator of AI tech that generates product listings automatically for retailers. In a recent press release announcing the launch of an AI tool on Google Cloud, the company touted what it described as a "close working partnership" with Google (which didn't respond to questions about the relationship).

What is clear is that readers don't like AI-generated content published under fake bylines. Shortly after our initial Sports Illustrated story, 80 percent of respondents in a poll by the AI Policy Institute said that what the magazine had done should be illegal.

At the end of the day, journalism is an industry built on trust. But descending into AdVon's miasma of fake writers and legal threats, it quickly becomes hard to trust anything connected to the company, from its word salad reviews to basic questions about which writers are even real people and whether AI was used to produce the articles attributed to them.

That's a lesson learned the hard way by Sports Illustrated, which became an internet-wide punchline after its fake writers came to light last year. (Its publisher at the time, The Arena Group, is now in chaos after firing the magazine's staff, losing rights to the title entirely, and seeing its stock price lose about two-thirds of its value in the wake of the scandal.)

Whether the rest of the publishing industry will heed that warning is an open question.

Some outlets, including The New York Times and The Washington Post, have debuted new teams tasked with finding highbrow, honest uses for AI in journalism.

For the most part, though, AI experiments in the publishing world have been embarrassing debacles. CNET got lambasted for publishing dozens of AI-generated articles about personal finance before discovering they were riddled with errors and plagiarism. Gannett was forced to stop publishing nonsensical AI-spun sports summaries. And BuzzFeed used the tech to grind out widely-derided travel guides that repeated the same phrases ad nauseam.

At its worst, AI lets unscrupulous profiteers pollute the internet with low-quality work produced at unprecedented scale. It’s a phenomenon which — if platforms like Google and Facebook can't figure out how to separate the wheat from the chaff — threatens to flood the whole web in an unstoppable deluge of spam.

In other words, it's not surprising to see a company like AdVon turn to AI as a mechanism to churn out lousy content while cutting loose actual writers. But watching trusted publications help distribute that chum is a unique tragedy of the AI era.

Disclosure: Futurism's parent company, Recurrent Ventures, previously worked with AdVon in 2022 via its partnership to distribute select content on third-party e-commerce platforms. This content was written by Recurrent’s contributors. Presently, Recurrent maintains a business relationship with them to test Commerce content internationally for select brands (of which Futurism is not one). AdVon content has never been published on Futurism or any of Recurrent's websites.

More on AI: Microsoft Publishes Garbled AI Article Calling Tragically Deceased NBA Player "Useless"