Who's running this election anyway? High turnover and threats plague election offices

RENO, Nev. ? Deanna Spikula lasted five years but quit amid relentless harassment, baseless accusations of treason, and death threats.

Her replacement lasted just over 500 days- and quit a few weeks after someone sent fentanyl-laced envelopes to her colleagues.

Now it's Cari-Ann Burgess' turn in the crucible known as the Washoe County Registrar of Voters office, where every one of the 18 people who worked there during the 2020 election has since quit. Statewide, almost every election administrator has left in the past 3? years.

"You have to be somewhat crazy to do what we do," said Burgess, who in January began serving as the county's interim chief elections official. "The negative publicity, the harassment."

A similar pattern is playing out nationally, with tens of thousands of longtime elections workers harassed out of their jobs by a small cadre of self-appointed voting experts and critics who have hounded clerks to switch to paper ballots, demanded hand-counted results, and insisted they be allowed to participate in ways that are normally barred specifically because they can introduce errors.

"It's not that turnover is something new," said Tammy Patrick, CEO for programs at the National Association of Election Officials. "What's new is the scope of it, the depth of it, the scale of it. Those who have left the field, it's understandable. A person can only take so much."

The unprecedented turnover means elections today are being run by less-experienced workers at every level. One nonpartisan group concluded departing elections officials took with them a collective 1,800 years of experience from a system that until 2020 was widely considered the international gold standard.

Elections experts say the turnover naturally raises questions about whether elections now will be more secure and accurate than in the past. But they insist the nation's elections officials ? new or not ? are up to the challenge.

"There is an increase in trust in elections today," said Kansas Secretary of State Scott Schwab, a Republican. "It's just the folks who trust elections are not as loud as the people who don't."

Unprecedented scope and scale of harassment

Harassment of elections workers nationally has been pervasive, persistent, and in some cases illegal. Former President Donald Trump is facing criminal charges that he and several co-conspirators improperly pressured election workers to overturn results and award him a second term as president.

The threats have been most significant in presidential battleground states, particularly places where Trump improperly insisted the votes were rigged.

Republicans responding to criticism of Trump and his "Big Lie" criticism often point to Georgia gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams, a Democrat, who in 2018 refused to concede her loss to Republican Gov. Brian Kemp.

But Abrams has repeatedly acknowledged Kemp won the election. Instead, she said she refused to concede in principle because she felt voter turnout had been suppressed, and she specifically said it was wrong for politicians to try to claim victory through fraud.

While Trump's criminal prosecution has drawn most of the attention ? which he uses to raise more money for his 2024 presidential campaign ? local elections officials have suffered a slew of threats.

The harassment is ongoing, as are prosecutions, including one arrest announced Thursday of a California man who allegedly left life-threatening messages on the personal cellphone of an Arizona election official.

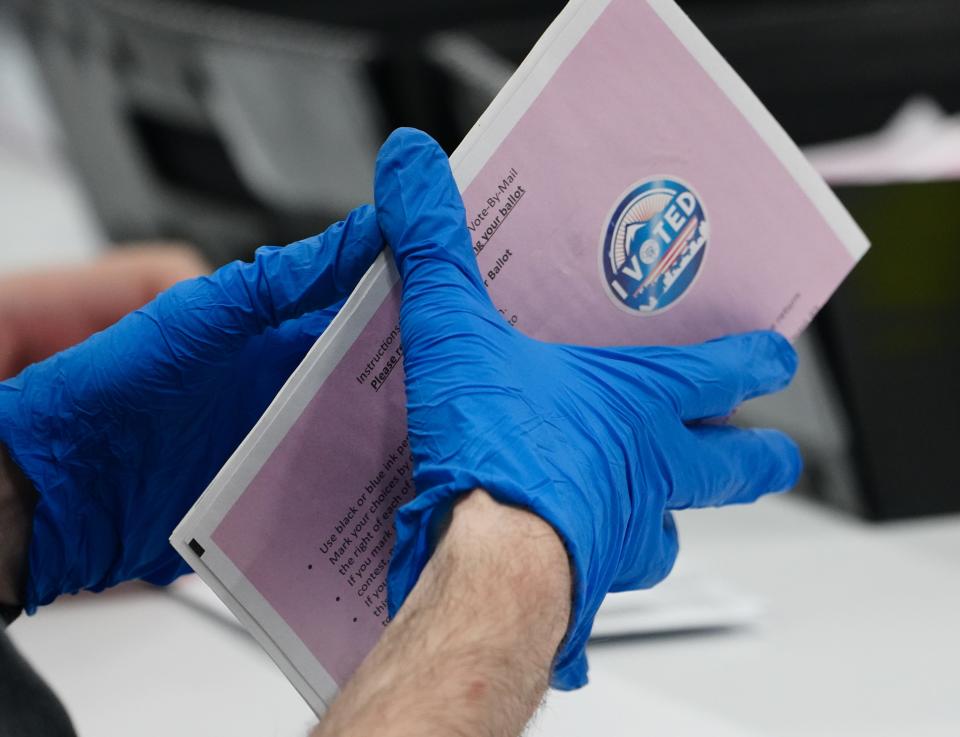

In November, someone sent at least four fentanyl-laced envelopes to elections offices in five states, delaying the counting of ballots in California, Georgia, Oregon, Nevada and Washington. Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, a Republican, said his office was distributing Narcan, an antidote to fentanyl, and called the mailings "domestic terrorism" that needed to be condemned by anyone who holds or seeks to hold elected office.

In 2022, a losing Republican candidate in New Mexico pleaded guilty to hiring two men who shot at election officials after they refused to overturn election results.

In 2023, a Texas man was sentenced to two years in federal prison for posting a Craigslist message calling on "patriots" to murder election officials in Georgia: "One good loyal Patriot deer hunter in camo and a rifle can send a very clear message," the man wrote, according to prosecutors.

In 2023, an Ohio man pleaded guilty to leaving threatening voicemail messages at the Arizona secretary of state's office, warning "you will pay with your life" for not producing the election results he wanted.

An Iowa man was sentenced to more than two years in prison for threatening Arizona elections officials, telling them they were going to be hanged for not producing the election results he wanted.

An Indiana man called a local Michigan elections worker and threatened that "ten million patriots" would surround and kill him in 2020.

A Massachusetts man pleaded guilty in 2023 to sending a bomb threat to an Arizona election worker, demanding she resign.

A New Hampshire woman pleaded guilty in 2023 to sending multiple threatening communications to a Michigan election official, including graphic photographs of a bloody, mutilated woman's body, along with photos of the official's child.

Turnover has consequences

A recent study found that at least half of all Americans in 11 Western states live in counties where the top election official has quit since the 2020 presidential election.

Experts say the loss of those experienced workers could cause problems like having ballots printed on paper that's too short, or pens that bleed through the ballots and potentially mess up computerized counts, which could slow results.

Who is left in elections offices? In many cases, less-experienced deputies and newcomers trying to fill the void. Adding to the concern: Some of those willing to take the jobs are 2020 election deniers with a specific agenda.

Patrick, who used to serve as the federal compliance officer for the Maricopa County Elections Department in Arizona, said the internal checks and balances that have always helped make American elections safe and reliable would generally prevent any bad actors from significantly altering results.

But she also acknowledged the systems were primarily designed to prevent honest mistakes, not stop criminal behavior. Still, she said, she expects the 2024 elections to be the most secure ever, precisely because election officials are now more on guard than ever.

“We can't put the genie back in the bottle,’’ said Amore, the Rhode Island secretary of state. “Elections officials have to do a good job. We have to be transparent in every single way so that people can see what the process looks like and can scrutinize that process, not that we're not in the most scrutinized election environment in history. We are.”

Nevada Secretary of State Francisco Aguilar, a Democrat, said he's confident elections will be run well, even with so many new administrators.

During the Feb. 6 Nevada presidential primary election, it took his office until almost two hours after the polls closed to post the first set of results ? and the first ones filed came from Burgess' office in Washoe County.

Aguilar said it's a mistake to think widespread turnover is entirely bad, because new leaders and staff bring new perspectives and approaches to tradition-bound elections offices.

He said that high-tech industries, banks and financial firms have developed secure systems that might be applicable to elections and that it's always worth asking if there's a better way to do things.

But Aguilar's office knows firsthand how little room there is for error. A few weeks after Nevada's presidential preference primary, voters became alarmed when the state's database erroneously showed many people had voted, even though they hadn't.

One Nevada lawmaker suggested the erroneous results demonstrated fraud, but Aguilar's office said it was something far simpler: a miscommunication between clerk's offices and the state's computer system about how the files were compiled. Aguilar's top deputies cited staffing and turnover as a key failure point.

"Given the many demands on the clerk/registrar’s time, short-staffing, turnover in county offices, etc. it was perhaps unrealistic to expect that the 'clean up' step would happen on a regular basis without communication from the Secretary of State’s office," they wrote.

Ultimately, most of the problems were resolved after the longtime clerk of tiny Lincoln County, pop. 4,500, shared screenshots of her computer showing the necessary steps. Most of her fellow clerks are new to the job since the last presidential election.

"I just happened to be the one who remembered that one little weird thing," said clerk Lisa Lloyd, who took office almost 20 years ago.

Becoming even more transparent

Like other experts, Aguilar said the vast majority of election deniers who seek to work in elections end up understanding that they are consistently fair and accurate. But there are some who will never be persuaded.

In an effort to increase both security and transparency, the Washoe registrar's office has set up a 24-hour webcam so people can observe every step of the counting process, increased security to prevent trespassing, and installed a glass-fronted penalty box so people can watch but not harass or throw things at election workers counting ballots.

On a recent visit to the Washoe registrar's office, Aguilar and Burgess were confronted by a handful of voters who have repeatedly attacked the county's election system. They complained the new glass-fronted booth makes it hard for them to see the entire vote-counting process in person and repeatedly interrupted when Aguilar and Burgess tried to address their concerns.

"We run some of the most secure and safest elections in the country – and they're accessible," Aguilar told the group. "So I think Nevada does a really good job of managing its elections across the state."

"Lie!" someone shouted back.

Experts say they're frustrated that nothing seems to quiet election critics, despite a myriad of courtroom losses and rejections by judges who have thrown out their complaints. Most recently, Texas-based group True the Vote told a Georgia judge on Feb. 14 that it couldn't provide any evidence to back up its claims ? echoed by Trump ? that Democratic activists illegally stuffed ballot boxes during the the 2020 election.

A spokesman for Raffensberger, the Georgia secretary of state, said the proceedings once again demonstrated that the group's oft-repeated claims were no more than "fairy-tale allegations." A few days earlier, someone had called in a fake bomb threat to his office.

Patrick from the NAEO said the problem is those who criticize or ask bad-faith questions perpetuate the myth there's something wrong. She said the constant questioning only fosters more distrust even though there's no substantive evidence showing those concerns are warranted.

"All too often what we've seen since 2020 is this attitude is 'what does it hurt' if we hand-count all our ballots, or continue to talk about the election being rigged or stolen," she said. "It undermines confidence in the system."

Burgess, the new Washoe County elections official, said she understands a significant part of her job is building back confidence, both with the public and her all-new staff. After needing nightly police escorts home during the 2020 election, she briefly left the field to help run an ice cream shop. She returned to the work, she said, through a sense of duty to what's right about America.

Despite the threats, despite the harassment, despite the constant questioning from a small number of her neighbors, she still believes elections are the cornerstone of democracy.

"This is what I signed up for when I took the job," said Burgess, who has a U.S. Constitution, the Bill of Rights and an American flag displayed in her office. "I know there are people who might want to cause me harm. But I know this is my civic duty because I love this country."

Contributing: Deborah Barfield Berry, USA TODAY; Mark Robison, Reno Gazette-Journal/USA TODAY NETWORK

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Ahead of 2024 election, threats rock elections offices nationwide