When was the last hurricane to hit California? Never. Hilary could change that

Rapidly intensifying Hurricane Hilary is heading toward the Pacific coast and could bring flooding rain to southern California later this week.

Although Hilary is forecast to make landfall over Mexico's Baja California peninsula over the weekend, a bobble to the west could mean a potential landfall in California, either as the first tropical storm in more than 80 years, or the first hurricane in recorded history.

While rain from hurricanes and tropical storms regularly hits the state, the hurricanes themselves do not. A 1939 hurricane, El Cordonazo, came close, but lost strength and became a tropical storm just before landfall near Los Angeles, historical records show. No tropical storm has made landfall since, according to federal weather officials.

Hurricanes need two things to stay energized: warm water and favorable winds. The California coast typically benefits from cooler water that flows southward along the coast and winds that tend to either shear the tops off hurricanes or push them westward away from the coast.

What does the National Hurricane Center say about the Hurricane Hilary forecast?

In the Southwestern United States, rainfall amounts of 2-4 inches, with isolated amounts in excess of 8 inches, are possible in southern California and southern Nevada, peaking on Sunday and Monday. Rainfall also is possible in western Arizona.

It's too soon to determine the location and magnitude of wind impacts.

Hilary could bring significant impacts, even after it dissipates.

How hurricane seasons differ

When the Atlantic hurricane season arrives on June 1 each year, a familiar sense of dread rolls over millions from Texas to New England who face the frequent threat of hurricanes and tropical storms that wipe out communities, flood homes and knock out power for days.

Massive coastal cities up and down the West Coast barely blinked when the Eastern Pacific hurricane season started on May 15. Although plagued with wildfires and earthquake risk, the West Coast mainland enjoys seemingly tranquil seas.

Mexico regularly gets hit with hurricanes and other parts of the Pacific, including Hawaii, face elevated hurricane risk this year.

So why don't residents from San Diego to Seattle also fear hurricanes? And could that change in a world where climate change is disrupting nearly every weather pattern?

It turns out sea surface temperatures nearshore and trade winds along the Equator matter, a lot. Calm winds and a cooler water current along California's coast act together to protect the West Coast.

READ MORE: Latest climate change news from USA TODAY

How does climate change affect you?: Subscribe to the weekly Climate Point newsletter

That's a striking feature of the West Coast, especially because tropical storms and hurricanes routinely make landfall south of San Diego in the Baja California Peninsula. There, much warmer water supplies more fuel for storms.

Has a hurricane ever hit the West Coast?

It depends on your definition.

Historic records show at least two hurricanes came very close. A hurricane with estimated 75 mph winds affected San Diego on Oct. 2, 1858, passing just west offshore, but not making landfall, according to a 2004 analysis by two hurricane researchers, Michael Chenoweth and Christopher Landsea, published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society.

HURRICANE FORECASTS: National Hurricane Center used to give 2-day outlooks. In 2023, it will forecast 7 days out.

INFOGRAPHIC: An inside look at the birth and power of hurricanes

The pair found a report in the Daily Alta California from a San Diego correspondent who reported "one of the most terrific and violent hurricanes that has ever been noticed by the inhabitants of our quiet city."

"Roofs of houses, trees, fences, ... filled the air in all directions, doing a large amount of damage, in and about the city, and its immediate vicinity," the account stated. "The streets, alleys, and roads, from a distance as far as yet heard from, were swept as clean as if a thousand brooms had been laboriously employed for months."

A hurricane named "El Cordonazo" approached Los Angeles on Sept. 24, 1939, but lost hurricane strength shortly before moving ashore. It set records for the most rainfall in September, dropping 5.42 inches in LA and 11.6 inches at Mount Wilson, according to records from the National Weather Service office in San Diego.

No direct landfalling hurricanes are shown in California in records kept by federal weather officials, although landfalls routinely take place farther to the south along Mexico's Baja California Peninsula.

However, at least 50 tropical storms or hurricane remnants have either affected or moved over California and Arizona, including storms that fell apart offshore and remnants of storms that moved north after making landfall somewhere to the south along the Peninsula.

In 1978, Norman moved over California as a Tropical Depression, tossing ships around and causing more than $300 million in damages. Its remnants later moved over into Arizona.

In 2005, Hurricane Emily's remnants arrived in California from the east, after it made landfall near the Texas/Mexico border and kept moving westward.

In 2022, Hurricane Kay was downgraded from a hurricane more than 300 miles to the south and had dissipated around 100 miles to the south, but tropical moisture associated with its remnants dropped up to 5.85 inches of rain at Mount Laguna, California, and 4.6 near Green Valley, Arizona.

Arizona also sees rain from tropical systems, said Isaac Smith, a meteorologist with the Phoenix weather service office. Storms and their remnants arrive every few years and can come from the Gulf of California and the Baja Peninsula and even the Gulf of Mexico. In October 2018, Smith said, remnants of two systems dropped 5 inches of rain, making it the wettest October on record in Phoenix.

Hurricane outlook for 2023: NOAA announces prediction for how many hurricanes will form

Why doesn't California get hurricanes?

Given its history, a hurricane landfall in California is not impossible, but highly unlikely for two reasons: Cold ocean water and upper-level winds.

The south-flowing cool-water California Current along the U.S. West Coast and northern Baja California ensures the water never gets warm enough to fuel a hurricane, according to NASA.

Along the East Coast, the Gulf Stream provides a source of warm (> 80°F) waters to help maintain the hurricane, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said. Ocean temperatures rarely get above the 70s along the West Coast, too cool to help sustain a hurricane’s strength.

So for the occasional eastern Pacific hurricane that does track toward the U.S. West Coast, the cooler waters can quickly reduce the strength of the storm. The remnants of such storms can move over the Southwest, bringing heavy rainfall.

In addition, winds in the region tend to shear off the tops of hurricanes, push storms to the west and northwest away from the coast and push away warmer surface waters, creating an upwelling of colder water.

Hurricanes tend to move toward the west-northwest after they form in the tropical and subtropical latitudes, according to NOAA. In the Atlantic, that often brings hurricane activity toward the U.S. East and Gulf coasts but it takes hurricanes and tropical storms away from the U.S. West Coast.

When is hurricane season?: Here's when hurricane season starts and what to expect in 2023

How might climate change impact eastern Pacific hurricanes?

Scientists aren't yet sure how human-caused climate change might specifically affect the frequency or intensity of hurricanes that form in the eastern Pacific basin, due to competing weather factors that affect the development of the storms.

"Sea surface temperatures are generally rising as the climate warms, which could provide more "fuel" for any hurricanes that do form," said Kim Wood, an associate professor in the Department of Geosciences at Mississippi State University.

"However, global warming also impacts large-scale atmospheric flow patterns like the North Pacific High," Wood added. "For example, if that high becomes stronger, then hurricane activity is likely to decrease, whereas that high becoming weaker could support increased hurricane activity. We need more years of data to fully evaluate current trends and thus better evaluate how climate change could impact eastern Pacific hurricanes affecting the U.S.," Wood said.

Hurricane season is here: Here's the list of names for the 2023 Atlantic hurricane season.

What's the hurricane forecast for the Atlantic region?

Because of the predicted hurricane-dampening El Ni?o, many forecasts for 2023 say a near- to below-average season is likely. However, unusually warm water in the Atlantic, in the regions where hurricanes typically form, could counteract the impact of El Ni?o.

NOAA said there’s a 40% chance of a near-normal season, a 30% chance of an above-average season (more storms than usual) and a 30% chance of a below-normal season. NOAA predicts that 12 to 17 named storms will form, of which five to nine will become hurricanes.

Top forecasters from Colorado State University predict that 13 tropical storms will form in the Atlantic, of which six will become hurricanes.

An average season sees 14 named storms, with seven becoming hurricanes.

But don't become complacent because this year's hurricane season might be "average." Even a below-average hurricane season can be deadly. So whether it's hurricanes, floods or wildfires, preparation is essential.

Hurricane wind scale: What is the Saffir-Simpson hurricane wind speed scale? Breaking down the hurricane category scale

What's the forecast for the eastern Pacific? And how does El Ni?o affect eastern Pacific hurricanes?

In the eastern Pacific Basin, 14 to 20 named storms are expected, NOAA said. Of those storms, seven to 11 are expected to be hurricanes. An average eastern Pacific hurricane season produces 15 named storms. The active season is due to the expected development of El Ni?o by late summer.

When an El Ni?o occurs, the Pacific is warmer than normal off the coast of South America, Central America, and along the equator.

Warmer ocean water provides more energy for the development and strengthening of tropical storms and hurricanes, Wood said.

"In addition to warmer water, there tends to be more rising air over the eastern Pacific basin during El Ni?o, which also supports storm formation," Wood said. "Finally, changes in atmospheric flow during El Ni?o results in lower wind shear in this region. Wind shear, which is a change in wind direction and/or speed with height, tends to prevent storms from developing or getting strong if they do develop, so lower wind shear can help increase hurricane activity."

Since 1950, more than half the times southern California was directly or indirectly affected by a tropical storm or hurricane or its remnants were during an El Ni?o, rather than during a La Ni?a or neutral conditions, according to weather service records.

What happened during last year's hurricane seasons?

In the Atlantic:

Fourteen named storms occurred in 2022, including eight hurricanes.

Two became major hurricanes: Fiona and Ian.

It was the seventh season in a row to produce a deadly landfalling hurricane on the U.S. mainland.

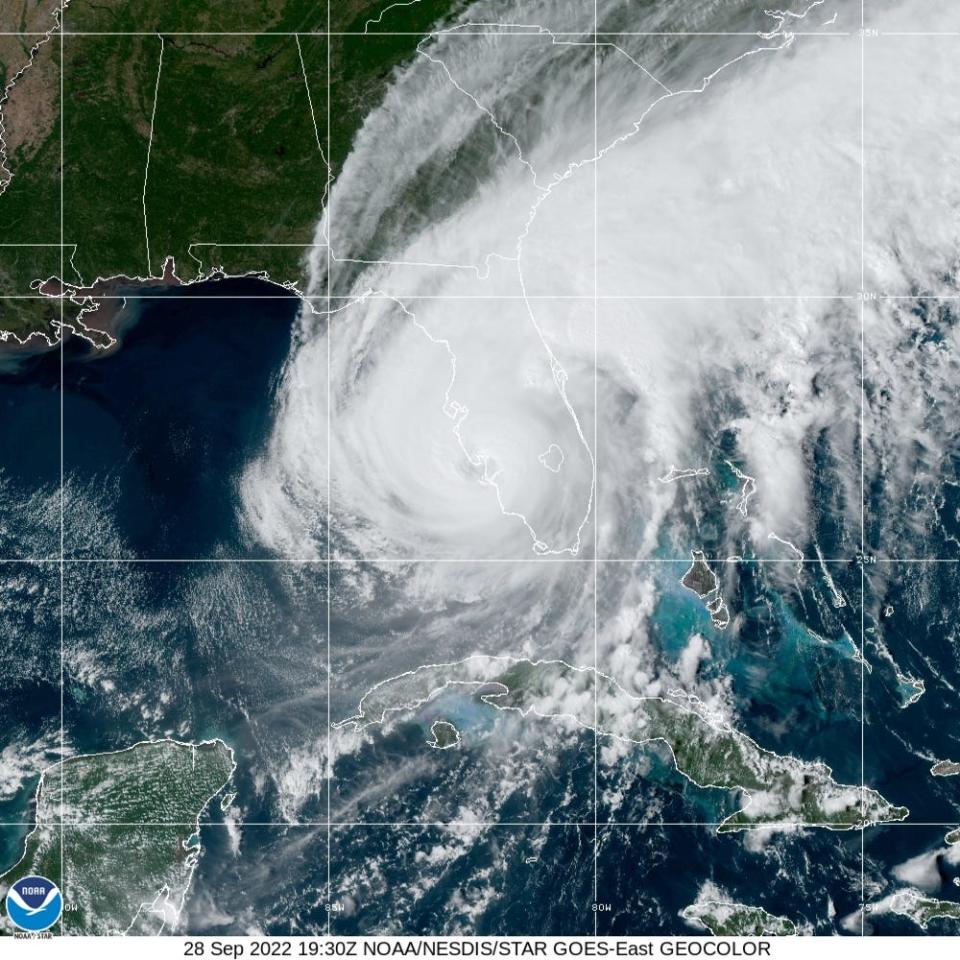

Hurricane Ian, officially classified as a Category 5 storm in a post-season analysis, claimed at least 156 lives.

In the Eastern Pacific:

An above-average 17 named storms, including 10 hurricanes

Four storms became major hurricanes, the average for the basin.

Dig Deeper

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Hurricane Hilary may hit California where tropical storm landfall rare