Un-Borkable: Kavanaugh heads into confirmation hearings on cruise control

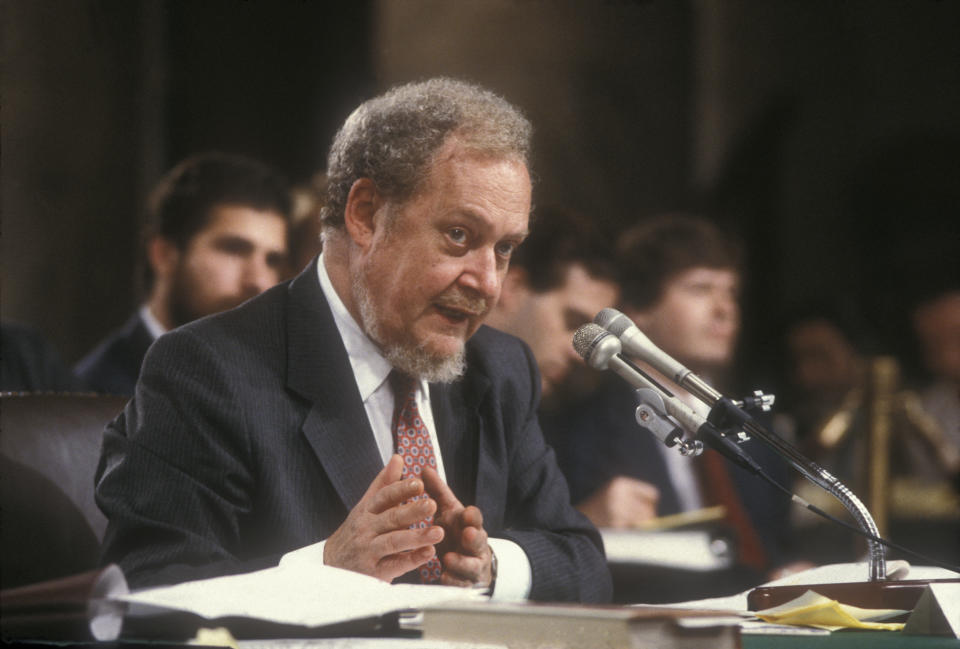

More than 30 years ago, Robert Bork’s nomination to the Supreme Court produced attention-grabbing hearings that took a toll on his already lackluster popularity with the viewing public.

“Bork came across on television as coldhearted and condescending,” the Washington Post’s Tom Shales wrote at the time. “He looked and talked like a man who would throw the book at you — and maybe like a man who would throw the book at the whole country.”

Bork’s nomination failed on the Senate floor by a vote of 42 to 58.

Yet when Circuit Judge Brett Kavanaugh takes his seat before the Senate Judiciary Committee at his Supreme Court confirmation hearings this week, he’ll face Republicans who are confident of collecting what may be the last significant reward of one-party rule before the midterm elections. Democrats have no clear path to stopping the installation of a justice who may solidify the court’s conservative majority for a generation.

On paper, Kavanaugh’s own personal unpopularity, his low-support positions on hot-button issues, the suspicions raised over withheld documents and the plague of scandal surrounding the president who appointed him may seem like the right combination of factors to produce a repeat of the Bork phenomenon. However, few in Washington expect anything so dramatic.

The nominees have changed their behavior, and so has the Senate.

“I think that the Bork hearing, being as impactful as it was back then, is a relic of a bygone era, because ever since nominees have sought to not answer questions,” said Brian Fallon, the executive director of Demand Justice, an organization opposing Kavanaugh’s nomination, and a former top aide to Hillary Clinton’s campaign.

Kavanaugh is less of an ideological cipher than the typical nominee to the high court. Through his rulings, his dissents, his outside writing and his public speeches, Kavanaugh has been unusually forthright about his judicial philosophy and aligned himself closely with former Chief Justice William Rehnquist and former Justice Antonin Scalia, who are both known as stalwart conservatives.

Republicans and Democrats alike describe Kavanaugh as a “known quantity,” even before the hearings begin. In that respect, Kavanaugh bears more than a passing resemblance to Bork. The similarities do not end there.

Like Bork, Kavanaugh arrives at his confirmation hearings as a sitting judge on the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, known only half-jokingly in Washington as “the second highest court in the land.” At the time of his nomination, Bork had served for five years on the D.C. Circuit; Kavanaugh has served for 12 years. And like Bork, Kavanaugh worked in the office of the U.S. solicitor general, although unlike Bork, he never held the top job.

There are other similarities: Both were nominated to replace the court’s most prominent swing voter, Anthony Kennedy in Kavanaugh’s case and Lewis Powell in Bork’s.

Similar to Bork, Kavanaugh’s vote is not expected to swing should he be confirmed.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, a cloud of legal jeopardy hangs over the president. For Kavanaugh, it’s the Russia investigation, while Bork’s nomination came hard on the heels of the Iran-Contra scandal.

Republicans, of course, view Kavanaugh’s well-documented conservative orthodoxy as a plus. “There have been nominees in the past who weren’t well known, and that gives people a little bit of anxiety. But with Judge Kavanaugh, we have 12 years to know who he is, how he acts and how he handles the law,” said Don Stewart, a spokesperson for Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell. Republicans, Stewart added, “have been very impressed with [Kavanaugh] for a long time.”

Kavanaugh’s opponents agree that he’s a known quantity. “You might usually enter these hearings with a strategy of trying to shake loose some glimpse of the nominee’s views on any of these issues that you’re trying to spotlight,” Fallon said. “In this case,” he added, “we have already, entering the hearings, a pretty good window into [Kavanaugh’s] views on the issues. There’s ample basis already for Democrats to mostly be united in opposition to him.”

As hearings begin, however, Democrats opposed to Kavanaugh are still pushing to unify their ranks in the Senate. The website of the coalition Fallon leads, www.whipthevote.org, counts only 26 senators who are firmly opposed to confirming Kavanaugh, with another 18 leaning that way; all are Democrats. The site describes the remaining five Democratic senators, along with Republican Sens. Susan Collins and Lisa Murkowski, as neutral.

“This will come down to a small handful of votes in the Senate,” Sen. Cory Booker said. “I will work hard in my official duties to try to bring to light the issues that should give senators pause.”

Democrats are focusing on Kavanaugh’s positions casting doubt on the constitutionality of the Affordable Care Act, opposing access to abortion and taking an expansive view of the power of the president. Sen. Dianne Feinstein’s office last week released the list of Democratic witnesses who will appear at the hearings, including experts on health care, reproductive rights, executive power and investigations of the president, as well as firearms, labor and environmental issues.

Kavanaugh is expected to make his first appearance before the Judiciary Committee on Wednesday this week, after a day of witness testimony.

On health care, Democrats can be expected to prompt Kavanaugh to expand on what they perceive as his opposition to the Affordable Care Act, the Obama administration’s signature health care law. Fallon has urged senators to ask the nominee about Trump’s argument that the law’s individual mandate is unconstitutional — a position administration lawyers are set to argue in a District Court in Texas this week, nearly simultaneously with the Kavanaugh hearings.

The administration’s position in that case, backing the complaints of a number of Republican state attorneys general, has been heavily criticized by legal scholars; however, past challenges to the health care law that faced similarly unequivocal criticisms from the academic community have nevertheless reached the Supreme Court and put the law in mortal danger. Kavanaugh has previously dissented from decisions upholding the constitutionality of the Affordable Care Act. The case in Texas could reach the Supreme Court relatively rapidly, and both Stewart and Fallon agree it is unlikely that Kavanaugh will weigh in on the substance of the case during the hearing.

On abortion, progressive activists have several lines of evidence they expect Democrats to pursue with the nominee. “Kavanaugh clearly is not somebody who believes fundamentally that the Constitution protects the right to access abortion in this country,” said Erica Sackin, a spokesperson for Planned Parenthood. She cited Kavanaugh’s rulings on the D.C. Circuit “to limit access to birth control and abortion,” Trump’s campaign pledge to appoint justices who would “automatically’ overturn Roe v. Wade and Kavanaugh’s appearance on the lists produced by the Heritage Foundation and Federalist Society, from which Trump picks his nominees.

Those conservative movement organizations are opposed to judicial recognition of reproductive rights. Sackin pointed out that a dozen cases concerning abortion rights are currently pending or have recently been decided by the circuit courts and could be soon appealed to the Supreme Court, where Kavanaugh could soon be the fifth vote for a decision restricting reproductive rights. In addition, a former Supreme Court advocate at the ACLU Legal Defense Fund pointed to a speech Kavanaugh made just last year to the American Enterprise Institute praising the late Chief Justice Rehnquist’s dissent in Roe as direct evidence of both Kavanaugh’s position on abortion and his broader skepticism of the panoply of unenumerated rights the Supreme Court recognized over the course of the 20th century.

One of the key issues will be Kavanaugh’s view on executive powers, which could have important repercussions for the ongoing investigation by Robert Mueller. Both Democrats and legal experts have noticed that Kavanaugh has espoused an usually broad view of executive power. Steve Vladeck, a law professor at the University of Texas at Austin, pointed out that Kavanaugh’s decisions show a special deference to the president that does not necessarily extend to executive branch agencies. Kavanaugh is “skeptical about Chevron,” Vladeck noted, referring to a 1984 Supreme Court case that calls on courts to defer to federal agencies’ interpretation of federal law. “He doesn’t think agencies should have that much power to interpret things on their own.” However, Vladeck added, Kavanaugh is “willing to give the executive branch in general the benefit of the doubt where national security is concerned, whereas he wouldn’t in other contexts.”

Kavanaugh served on the Ken Starr investigation, where documents show he was one of the most zealous prosecutors in pursuing the minute details of the president’s affair with Monica Lewinsky. After he moved into the Bush White House, Kavanaugh publicly changed his mind and declared that investigations like Starr’s intruded too much on the president’s prerogatives.

Democrats have raised concerns that Kavanaugh’s deference to the president could interfere with or endanger the Mueller investigation and other inquiries, including the Manhattan U.S. Attorney’s parallel investigation into associates of the president.

“I have serious concerns about a president being able to pick their own judge,” Sen. Booker said, adding that Trump is “credibly accused of being an unindicted co-conspirator” because of the recent guilty plea in New York by Trump’s former personal attorney Michael Cohen, which implicated Trump. “The fact that I can even say that should shock people,” Booker continued. “This is not normal, and [Kavanaugh] should recuse himself.”

The demand that Kavanaugh pledge to recuse himself from any cases involving Trump’s personal legal jeopardy is expected to emerge as a point of controversy during the hearings. Kavanaugh reportedly has no plans to make such a pledge.

However well Democrats understand Kavanaugh’s judicial predispositions, they insist that they are not satisfied that they’ve seen enough of his public service record. Republicans scheduled the Kavanaugh hearings for this week even though senators do not expect to receive some requested documents Kavanaugh authored during his time in the Bush White House until next month. These requests themselves were limited to far less than Democrats wanted by Chuck Grassley, the Republican chairman of the Judiciary Committee.

Stewart, McConnell’s aide, observed that any controversy over Bush-era documents amounted to “Democrats self-incriminating that they weren’t paying attention 12 years ago” during Kavanaugh’s confirmation to the D.C. Circuit, when they could have made the same requests.

The document production process this time around is equal parts restrictive and byzantine. William Burck, a private attorney (and former Kavanaugh deputy) has been prescreening taxpayer-owned records on behalf of former President Bush before they are produced to the Senate. Last Friday, he sent a letter informing senators that his team is withholding, at the direction of the Trump White House, over 100,000 pages of documents based on the assertion of “constitutional privilege.”

The volume of missing documents raises an uncomfortable analogy to Circuit Judge Jay Bybee’s confirmation in 2003. At the time, the fact that Bybee had signed a series of secret and legally unsound memos for the Bush administration was still classified. These secret memos authorized the torture of prisoners and the CIA’s rendition, detention and interrogation program, with its archipelago of secret prisons around the world.

Bybee faced essentially no critical questions from the Judiciary Committee at his hearings in early February 2003 and sailed through his confirmation by a vote of 74-19. Only later, after the photos of abuses at Abu Ghraib were disclosed, did a firestorm erupt about the illegal practices Bybee’s memos authorized, leading some senators who voted for him to demand his resignation.

Today, Bybee still holds a lifetime seat on the Ninth Circuit.

Hunter Walker contributed reporting from Washington, D.C.

_____

More Yahoo News stories on the Supreme Court: