Two decades later, 2004 is remembered as the 'mean season' as hurricanes shredded Florida

It’s been 20 years since a mutinous atmosphere rose up against Florida, besieging it on all sides with a succession of furious hurricanes, a pageant of perdition, a caravan of despair.

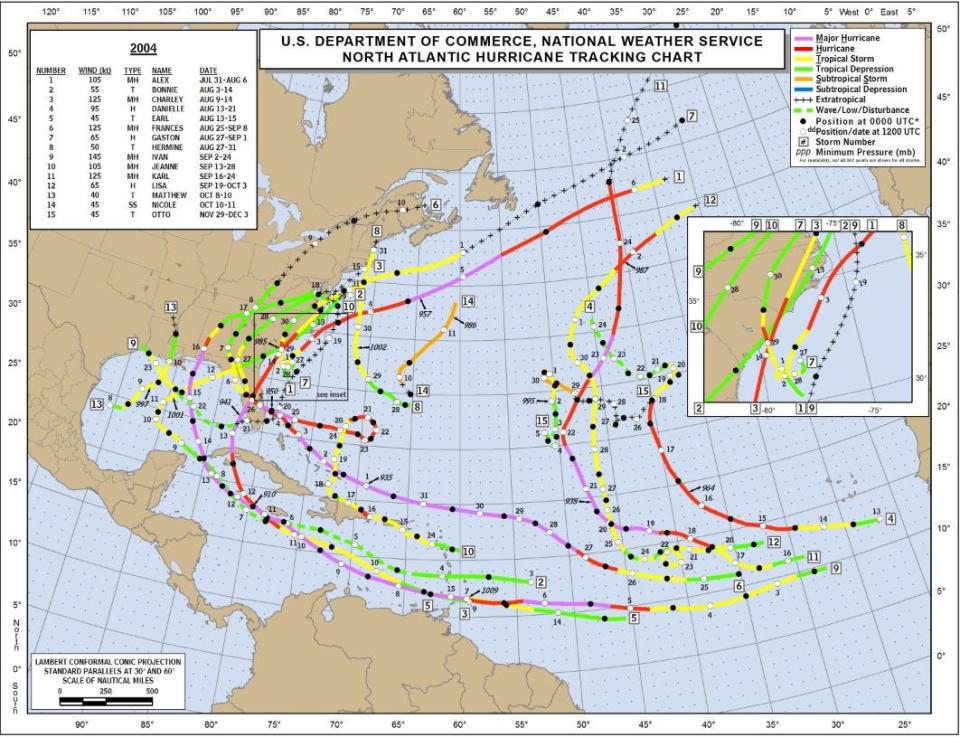

Charley, Frances, Ivan and Jeanne.

In a stretch of time just longer than it takes the moon to ripen and be reborn, three of the storms made landfall on Sunshine State beaches during the late summer and early fall of 2004. Ivan, nicknamed “the terrible” for its brutality, hit just into Alabama where its tropical wrath chopped the Interstate 10 bridge into pieces and turned Pensacola Beach homes to pulpy ruin.

Frances, a lumbering Category 2 at landfall, and Jeanne a more efficient Cat 3, inexplicably hit the same spot on Hutchinson Island in Martin County. Charley shocked southwest Florida with a rapid intensification to a Cat 4 and a subtle shift to the right that saved Tampa but pummeled Punta Gorda.

All told, the storms were directly or partly blamed for 145 deaths in the United States and tallied up just over $50 billion in damages.

In the two decades since, worse storms have come and gone, threatened and blustered, bullied and bulldozed, but in 2004 many Floridians were still hurricane ingenues. Andrew (1992) seemed ancient history, 1999’s Floyd terrified thousands into a ragged evacuation, then veered north.

After years of unrequited scares, thunderstruck Floridians lost their hurricane innocence in groaning homes and storm-darkened bathrooms with no smart phones or radar apps or growling generators for comfort.

“There is nobody who can move to Florida today and not know we have hurricanes, but back then it was different,” said Fox Weather hurricane specialist Bryan Norcross. “Andrew felt like a freak. There was Floyd, and there had been scares before Andrew, but there was this idea that the storms always turned north.”

Three hurricane landfalls in Florida in one year a rare catastrophe

In the annals of climatology, only a handful of years have seen three hurricane landfalls in Florida dating back to the late 1800s. Those were 1871, 1886, 1964, 2004, and 2005, according to Colorado State University senior research scientist and hurricane expert Phil Klotzbach.

After 2005, another hurricane wouldn’t breach Florida until 2016’s Hermine.

In 2004, hurricane forecasting was rapidly improving, said Max Mayfield, the director of the National Hurricane Center from 2000-07. Meteorologists had gained enough confidence to increase forecasts from three to five days in 2003 and predicting size — the extent of tropical storm and hurricane force winds from a storm’s center — started in 2004.

Still, the number of storms that would crisscross Florida was a surprise to even the most seasoned meteorologists.

Appetite for destruction: Palm Beach County hurricanes through the years

“I don’t remember anyone saying it would be a hyperactive season,” Mayfield said. “I surely don’t remember anyone on the face of the Earth saying Florida was going to get hit by four strong hurricanes.”

The atmosphere that year was giving scant clues as to its intention.

Klotzbach, the lead author of the seasonal hurricane forecast for CSU, said the large-scale environment wasn’t a classic setup for a busy hurricane season.

There was a weak El Ni?o, whose reputation is to quash storms with shredding wind shear. The sea surface temperatures in the main runway between Africa and the Caribbean were not uniformly above average, and slightly cool in the eastern Atlantic.

CSU and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration called for slightly more activity than normal. Both undersold the number of major hurricanes that would take advantage of a slip in wind shear during the height of the season, Klotzbach said.

Although the 15 named storms that formed in 2004 were three higher than the average at the time (the average is up to 14 now), the accumulated cyclone energy, or ACE, they produced was 227. That's more than double what was experienced during an average year.

Even in 2020, when there were a whopping 30 named storms, the ACE was just 180.

Also at play in 2004 was a steering flow from a strong Bermuda-Azores high. The yawning clockwise swirl of winds in the Atlantic fired hurricanes at Florida like baseballs from a pitching machine giving them no chance to curve around its western flank and out to sea.

“There’s nothing like being tested by fire to see how you’re going to respond,” said Bob Weisman, who was administrator of Palm Beach County in 2004. “We hadn’t been hit hardly by anything before then. People don’t appreciate the potential impacts until they actually happen.”

2004's hurricanes challenged forecasters with their eccentricities

Norcross said the storms of 2004 were all very different.

Tiny Charley exploded from a Cat 2 to a Cat 4 in just five hours. Frances ballooned, dawdled, stalled then shambled ashore at 7 mph. Ivan lived for 22 days as a classic Cabo Verde storm — the scariest kind. Jeanne did a loop southeast of Florida then punched the gas toward the Treasure Coast.

But Charley was first. It crossed Cuba in only 90 minutes, reaching Cayo Costa in Lee County on Friday, Aug. 13 with 150-mph winds. It was the strongest hurricane to hit Florida since Cat 5 Andrew’s 165 mph landfall in 1992.

It left a fretful impression, tossing a manatee from Estero Bay onto Fort Myers Beach, trashing mobile homes along the Peace River and causing the iconic Shell Factory's sign in North Fort Myers to lose its S so that it aptly read "Hell Factory.”

“It’s a day I’ll never forget,” said Dan Brown, branch chief of the Hurricane Specialist Unit at NHC.

Brown worked in the Tropical Analysis and Forecast Branch at the NHC in 2004 and was supporting the lead forecaster during Charley. His parents were in Bonita Beach.

“My parents were in harm’s way. It was making a right turn and rapidly strengthening,” Brown said.

But Charley’s damage was mitigated by its speedy 20 mph tear through the state and hurricane winds that reached just 5 to 6 miles from center. Brown’s parents lost electricity but had little to no damage.

Palm Beach County's hurricane drought : Why hasn’t Palm Beach County been hit by a massive storm lately? Well, it ain’t science

Charley’s track is still a sore spot for some. Although its landfall was within the cone of uncertainty, just 12 hours ahead of landfall the center of the forecast path was still taking it toward the west-central coast of the state closer to Tampa.

Just a small deviation aimed it farther south instead.

“Most of the emergency managers understand that even with satellites and radars and computer models, the atmosphere is so complex, we are never going to have a perfect forecast,” Mayfield said. “A lot of us understand that, but a lot of people in the public do not.”

Mayfield said a FEMA official called him after Charley and asked if that was it for the season.

It was just the beginning.

Frances was a long-lived Cabo Verde storm that formed as a depression on Aug. 24. It proceeded as expected until its steering winds went slack, it slowed, and grew corpulent with hurricane-force winds extending up to 85 miles from its center. When it reached Hutchinson Island at 1 a.m. Sept. 5 as a Category 2 storm, NHC specialists wrote “finally” in their forecast.

It was still crawling, however, and some areas spent more than 24 hours buffeted by dangerous winds. Power outages affected up to 6 million people. Ice was like gold, all intersections became four-way stops with no traffic lights working, roofs were peeled back, the Lake Worth Pier was in pieces and curfews were enacted.

“Decision-making in a time like this is incredible,” said Weisman, who was not a fan of curfews. “I felt a very high level of responsibility to make the right calls.”

Ivan was another classic Cabo Verde hurricane fortified by at least three bouts of rapid intensification on its journey into the Gulf of Mexico. Ahead of landfall, hurricane-force winds extended approximately 105 miles from its center with tropical storm-force winds reaching 295 miles. It crashed into Alabama in the inky darkness of 2 a.m. on Sept. 16 as a Category 3 hurricane.

Ivan’s storm surge reached 10 to 15 feet from Destin, Florida to Mobile Bay. Perdido Key was leveled.

But it wasn’t enough to harry just the Gulf Coast. It produced an outbreak of about 115 tornadoes over three days and through nine states. Torrential rainfall of 3 to 7 inches spread from Alabama to New England.

More: Remembering the hurricanes of 2004's 'Mean Season'

“This isn’t what we normally see,” said John Cangialosi, a senior hurricane specialist with the NHC, about the widespread impacts of Ivan.

Then there was Jeanne. Despite forming near the Leeward Islands on Sept. 14, Jeanne teased Floridians for more than 10 days as it meandered in the Atlantic, crossing its own track before reaching Hutchinson Island Sept. 26 as a Category 3 hurricane.

“It wasn’t clear at all where Jeanne was going to go until it finally started to move and it was like ‘Oh my God, can you believe it went into the same place!’” Norcross said.

At one point, Weisman exhaled, thinking Jeanne was no longer a threat as it pirouetted off the coast. But it was a double bruising for Palm Beach County and devastating for Martin County just three weeks after Frances.

“It was insult to injury,” said David Sharp, meteorologist in charge at the National Weather Service office in Melbourne.

People were living under blue tarps, had used up their hurricane supplies, and there was still debris everywhere from Frances, which provided more ammunition for Jeanne.

“It was starting to damage the psyche of the people,” Sharp said. “Jeanne was about the people, and perseverance.”

From destruction to opportunity

There was some good that came out of the 2004 hurricane season, and subsequent havoc of 2005, Mayfield said.

When then-President George W. Bush visited the NHC, Mayfield passed along a wish list of equipment and personnel the NHC needed.

Added to the NHC’s budget was money for four more hurricane specialists and additional equipment, such as Step Frequency Microwave Radiometers for Hurricane Hunter airplanes. The radiometer can measure the surface wind speeds over water by analyzing the amount of sea foam stirred up.

Before the radiometers, forecasters estimated wind speeds based on what the airplanes could measure at 10,000 feet.

“It wasn’t a terribly busy season in terms of total numbers,” Norcross said about 2004. “But these were all extremely different storms and they came one after another. It was nonstop.”

Early forecasts for the 2024 hurricane season are predicting another over-achieving year for tropical cyclones as the storm abetting La Ni?a teams up with ocean water that is 3 to 7 degrees warmer than normal. It's enough of a concern that Florida Division of Emergency Management Director Kevin Guthrie said the state is preparing for a year similar to 2004.

The "mean season" in 2004 proved costly in lives and damage

Charley: 10 direct deaths, 25 indirect deaths, damages $15.1 billion

Frances: 5 direct deaths, 42 indirect deaths, damages $9.50 billion

Ivan: 25 direct deaths, 32 indirect deaths, damages $18.02 billion

Jeanne: 6 direct deaths, no indirect deaths included is storm report, $7.66 billion

*More than 3,000 people in Haiti died in Jeanne.

Source: National Hurricane Center post-storm reports with damages updated in 2011

Kimberly Miller is a veteran journalist for The Palm Beach Post, part of the USA Today Network of Florida. She covers real estate and how growth affects South Florida's environment. She chased storms from the Keys to Pensacola Beach during the 2004 and 2005 hurricane seasons, including covering Hurricane Charley from Fort Myers Beach. Subscribe to The Dirt for a weekly real estate roundup. If you have news tips, please send them to [email protected]. Help support our local journalism, subscribe today.

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: Hurricanes Charley, Frances, Ivan, Jeanne hit Florida in 2004 mean season