Trump may be indicted in Georgia. But 2020 still casts a shadow over its elections

ATLANTA – Sitting in his office in Georgia’s gold-domed Capitol, Brad Raffensperger said he was proud his state “protected the vote.”

Raffensperger was on the receiving end of the phone call after the 2020 election in which then-President Donald Trump pressured him over and over to change the outcome in Georgia, saying, “I just want to find 11,780 votes.”

To the soft-spoken engineer turned secretary of state, that’s all past now. His office was decorated with a patriotic eagle painting, given to him after he stood up to Trump’s pressure. His state, he contended, emerged with elections that are even more secure and accessible.

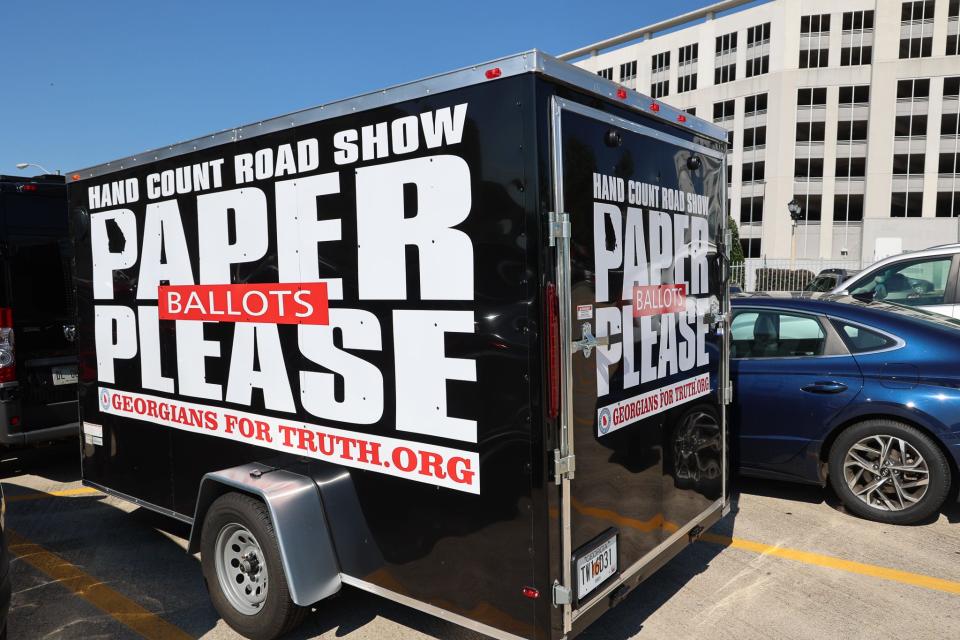

As Raffensperger spoke, though, just one floor above him speakers had filled the state elections board meeting to overcapacity. Suspicious of the Dominion-made voting machines, they lined up to demand paper ballots. “Until we can get rid of these machines,” attendee Jeff Jolly said outside, ”our winners are handpicked by a small group here in this building.”

About a mile from the Capitol is ground zero for some of the claims of election fraud: State Farm Arena, where election staff working around the clock at a vote tabulation center were then falsely accused of being “election scammers.” Their defamation lawsuit against Trump attorney Rudy Giuliani is still in court.

And just outside Raffensperger’s windows, almost visible, were the orange traffic barricades and police cars ringing the Fulton County Courthouse. There, a grand jury indictment in the investigation of efforts to overturn the 2020 vote was expected any day – an indictment that could come as early as Tuesday and may well include Trump himself.

To some Georgians, a Trump indictment would be a step toward justice; to others, a sign of just how broken the system is. But no matter the indictment, or any trial, or the desire many people here have to move on, there’s no outcome that seems likely to lift the shadow of 2020.

Voting rights advocates say the election and its aftermath left an enduring imprint on access, election politics and simple trust in Georgia, one of America’s most pivotal swing states.

They point chiefly to the state’s sweeping overhaul of elections in 2021. Republican legislators said the changes brought election security. Voter advocates and civil rights leaders say it built lasting barriers to voting access – an attempt, they believe, to undercut the growing clout of Democrats and Black voters.

The state also allowed unlimited citizen challenges to other people’s voter registrations – and right-wing activists filed so many, they swamped some election offices. Election offices were banned from seeking outside funding, which opponents viewed as unfairly helping Democratic counties. After years of threats and intimidation, election and poll workers are scarce.

For some voters – left to make sense of nearly three years of conflicting messages and investigations, of allegations and legislation – all this makes them push a little harder. They know the state that was under fire for voter access issues even before 2020. The year’s fallout fuels their determination to vote.

That’s not true for others, though, who have become convinced the outcome is decided by forces beyond the ballot box.

“A lot of this really goes back to the big lie – the idea that something was wrong with our election and our electoral system, and it has to change. And of course, we all know that's not true," said Anthony Michael Kreis, a Georgia State University election law professor. “Yet major pieces of public policy have been shifted in response to that lie.”

A land of surveillance video, allegations and threats

Outside an Atlanta coffee shop in early August, Richard Barron recalled the night he got a text from a reporter asking him how he felt.

Barron had no idea what she was talking about, but he soon would understand.

Donald Trump, then the outgoing president, had held a rally in Valdosta, Georgia, to support the Republican in the hotly contested runoff election for the state’s Senate seat. He had fired off false conspiracy theories about stolen elections and voter fraud, and had flashed Barron’s picture on the big screen.

Next came a flood of new threats. One message warned Barron he’d be “served lead.”

“That’s when I really started getting harassment,” he recalled. “I finally got a police officer to stay outside the house when I would sleep at night.”

It’s not as if Barron, Fulton County’s elections director, had never been embattled. Long before, he had faced problems with lines at polling places, administrative snafus and other issues.

He led the department during 2018’s bitter governor’s race, when Stacey Abrams narrowly lost to then-Secretary of State Brian Kemp. Officials rejected hundreds of absentee ballots. Democrats claimed voter suppression. Lawsuits continued for years.

The following year, Georgia purchased a new voting system made by a company that would soon be a household name: Dominion Voting Systems. The year after that, the COVID-19 pandemic put mail-in ballots into broad use.

Meanwhile, the stakes of elections in Georgia were mounting. The once reliably red state became a swing state that put 16 electoral votes up for grabs.

When Biden narrowly won Georgia in November ? the first Democrat to win the state since 1992 – Trump alleged fraud. Among his targets were Fulton County, the state’s most populous county.

After Trump demanded a hand recount, a statewide hand recount and a subsequent recount found Biden had won by about 12,000 votes.

But Trump’s claims continued. There were allegations of manipulated ballots. Fraud. Supposedly breached election equipment. Soon, Trump allies like Giuliani and then-White House chief of staff Mark Meadows were visiting Georgia.

In the months after the election, Barron’s staff faced pressure like never before.

Meeting with Georgia lawmakers that December, Giuliani played surveillance footage that included two of Barron’s employees – Ruby Freeman and her daughter, Wandrea “Shaye” Moss – at State Farm Arena.

Giuliani said the footage showed the women “surreptitiously passing around USB ports as if they are vials of heroin or cocaine,” the Associated Press reported.

What they were actually passing, as Moss would later explain to the Jan. 6 congressional committee, was a ginger mint. But the threats against them exploded.

Trump, in his infamous phone call to Georgia, would falsely call Freeman an “election scammer” at least 18 times.

They were forced to leave their home for two months at the urging of the FBI.

Moss, who is Black, said she received messages “wishing death upon me. Telling me that I’ll be in jail with my mother. And saying things like ‘Be glad it’s 2020 and not 1920.’”

“There is nowhere I feel safe,” Freeman told the congressional committee.

This June, a Georgia investigation of the allegations of fraud at the State Farm Arena ballot processing center cleared the two women of any wrongdoing.

Biden’s inauguration didn’t end the pressure. Barron said he continued to take criticism from state elections officials and some local politicians. Fulton County, at the behest of Republican legislators, became the first county in Georgia to undergo a new performance review. Barron’s office faced a possible state takeover.

Finally, in late 2021, he resigned.

Barron, nearly two years later, got through an entire coffee drink on a coffee shop patio near Atlanta’s Ponce City Market as he recounted the years of tumult.

The partisan acrimony took a toll. He struggled to find work in Atlanta, he said. For a while, he drove for Uber. He’s not sure if he can ever work in elections again.

“I started losing faith in the whole ... everything,” he said.

But his leaving office was just one chapter in the fallout from 2020. By then, another battle over elections in Georgia was well under way.

Canceled registrations, new restrictions and voter backlash

At the dining room table of his home east of Atlanta, a red-sided ranch tucked in a quiet neighborhood of neat lawns and leafy trees, Donel Peterman held his phone, typing his name into an app that shows whether a person is still registered to vote.

It’s something the 70-year-old former public transit supervisor regularly shows to people at his church, ever since the time his name ended up falling off the list.

In 2017, he found himself among more than a half-million people whose registrations were canceled under the state’s "use it or lose it” law. State officials defended the policy as voter-role maintenance and denied any nefarious intent, but critics said the system had a high error rate and disproportionately impacted Black voters.

Georgia declares registrations “inactive” after five years in which those voters do not participate in elections, contact or respond to elections officials or update their registrations – often because they moved. Those voters’ registrations are then dropped from the rolls if they don’t participate in the next two general elections.

Except Peterman says he had not moved – or missed multiple elections.

“This is totally ridiculous,” he recalled thinking at the time. He had to re-register to vote.

Then came 2020. And Peterman saw what he viewed as new hurdles to the vote.

In 2021, after Democrats had won two Senate runoff elections, a Republican-led legislature passed a sweeping election law.

Supporters said it was aimed at restoring voters’ confidence and making elections more secure in the wake of 2020. Gov. Kemp said it would make it "easy to vote, and hard to cheat." Critics said that was a pretext, and that the law would disproportionately suppress Democratic votes.

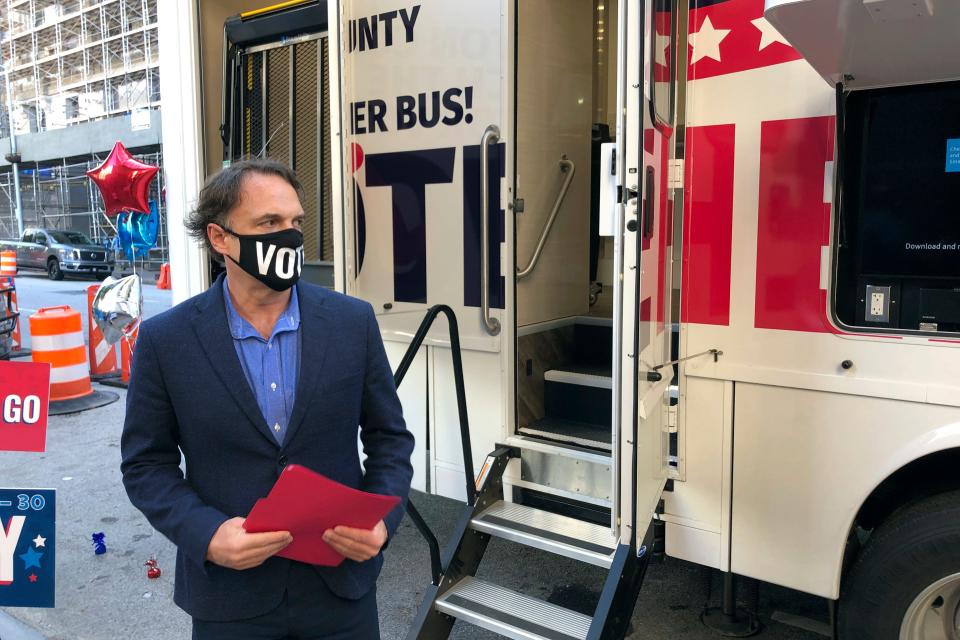

Known as SB 202, the law drew criticism on a number of provisions. It limited the number of polling places, added voter identification requirements to get absentee ballots, shortened the time to request them, and limited ballot drop boxes. That caused the number in Fulton County, for example, to drop from more than three dozen to 7. The county’s mobile-voting buses were banned.

The law also shortened the time between an election and a run-off election, shortening the time for voters to receive and return absentee ballots. It limited who could distribute absentee ballots or assist someone with an absentee ballot, a change advocates say impacts voters with disabilities.

And it gave the legislature more control over county election offices. All that came on top of 2021 redistricting, which the ACLU has argued diluted the power of Black voters.

Critics said SB 202 made it harder to vote. They said it would disproportionately affect people of color. Biden called the law “un-American” and the Department of Justice challenged provisions in court. Major League Baseball moved its All-Star game out of Atlanta in protest.

Georgia wasn’t the only place taking aim at elections laws, either. Fourteen states passed 22 restrictive laws in 2021. More did so this year, according to the Brennan Center for Justice, a nonpartisan policy group. At the same time, other states expanded voting rights to make ballot access safer and easier.

In Georgia, voter access groups responded by redoubling the get-out-the-vote efforts that had powered the Democratic wins in 2020.

Bishop Reginald Jackson, who leads more than 500 African Methodist Episcopal churches in Georgia, helped create the group Faith Works, a network of churches that conducted canvassing and registration drives, and encouraged early voting.

Helen Butler, head of the voting access group the People’s Agenda, said they too provided more rides to the polls than they had in the past.

Despite the worries, overall turnout during the general election was strong, drawing 56.9% of registered voters, according to the Secretary of State’s Office.

According to the Brookings Institution, Georgia saw gains between 2018 and 2022 in white voters but a turnout decline among nonwhite voters. Still, its 2022 nonwhite turnout rate still ranks fourth among all states.

Raffersperger says the strong turnout showed that voter suppression was a myth and concerns about SB 202 overblown. A University of Georgia study found more than 90% of voters had said it was easy to cast a ballot.

Jackson and other voting rights leaders credited turnout efforts and people’s determination to vote in spite of the law, and said surveying those who voted left out people who weren’t able to vote.

Andra Gillespie, a political science professor at Emory University, said the impact of SB 202 has yet to be determined.

In July, U.S. House Republicans introduced a new federal elections bill modeled after Georgia’s law.

At home east of Atlanta, Peterman is retired. His wife recently retired, too. They keep a neat home and have a pet bird named Jingle.

Retirement is good. It means more time to volunteer at a political action ministry at his church, helping educate others about the vote. Some people there believe it just doesn’t matter, he said, that the outcomes will be manipulated anyway.

Peterman – a Democrat, who says he sometimes votes Republican, depending on the candidate – doesn’t think that. He said his own experience – having his record temporarily purged, watching new laws come down and new district lines go up – has only made him more determined to vote.

He votes during the state's early voting window to make sure his vote is counted. Give Gov. Kemp credit for standing up for Trump, he said. But he isn’t happy he signed off on voting bills that concern him.

Still, he thinks efforts viewed as tilting the scales in favor of a particular party have backfired and hopes that will deter those strategies in the future.

“What they’re doing is pissing people off,” he said. “People are going to come and grow the vote.”

Peterman walked from his dining room through the garage, past Jingle’s cage into the leafy green light of a late Georgia summer. He’s watching, like everyone else in Georgia, for the indictments. Maybe, he says, they will stanch the most blatant attempts to sway elections and underscore something that to him seems basic.

“Elections need to be fair and square,” he said.

But what that means in Georgia can, at times, depend on who you ask.

A world of election information and disinformation

Jeff Jolly had made it as far as the Georgia Board of Elections meeting, but he couldn’t get inside. The room had reached capacity.

Jolly stood outside as some walked across the street to watch it on a TV feed.

Inside, people were demanding the state use paper ballots that could be hand-counted for better election security. Jolly agreed.

Some had arrived in a passenger van that towed a trailer pasted with the slogan “Paper Please.” “We call it the war wagon,” Jolly said.

The semi-retired pecan businessman wore a T-shirt with the logo “Georgians for Truth,” a group that supports the ballot change.

While opponents of changes like SB 202 think Georgia’s election procedures are too restrictive, Jolly – who chairs the local Republican Party in Grady County, way down near the Florida line – thinks they aren’t strict enough.

Jolly said he believes Fulton County’s anticipated prosecution of Trump is a “joke” and that the so-called fake electors who sought to certify Georgia for Trump were legitimate. But 2020, he said, “it’s over. We’ve got to move forward. To make sure we have a true election next year.”

Garland Favorito, a founder of the group VoterGA, wants to, too. He contends that fraud, errors and irregularities meant the 2020 election never should have been certified. He blamed courts for stymying their efforts to prove it thus far.

While there have been some improvements in election security since 2020, Favorito says, there haven’t been enough to “secure the 2024 elections.”

Lingering doubts about elections security led rural Spalding County to require automatic hand recounts for elections earlier this year, which followed a move to cancel Sunday voting, a change protested by Black voters, according to The Guardian.

SB 202 also allowed residents to make unlimited voter challenges against anyone in their county. Rahul Garabadu, senior voting rights attorney for the ACLU of Georgia, said such challenges were once an arcane part of election law, meant for family members or neighbors to alert officials that someone had moved or died.

Last month, a ProPublica investigation found that the vast majority of the challenges since SB 202 became law ? about 89,000 of 100,000 ? were submitted by six right-wing activists.

Of those challenges, roughly 11,100 were successful ? at least 2,350 voters were removed from the rolls and at least 8,700 were placed in a “challenged” status. However, the investigation found that many would have been eventually corrected by routine voter-roll maintenance.

One resident who was challenged is Carry Smith, 41, who lives in Savannah and works with a voting rights group. After moving there a handful of years ago, she said, she used a mailbox business as her address while she looked for a place to live. She thought she later updated her voter registration but found she was still registered at the business. Luckily, she noticed the piece of mail about it and was able to change her address to remain on the rolls.

“I think if I didn’t check my mail, I wouldn’t have known,” she said.

In Gwinnett County, which stretches across the increasingly Democratic northern Atlanta suburbs, those challenges created a month’s worth of work in fall 2022, said county elections supervisor Zach Manifold, as he walked among of boxes that included election materials from 2020 that must be retained because of ongoing lawsuits.

In filing them, activists compared change-of-address and other databases with the county’s voter rolls, the AP reported. Manifold said that of the roughly 12,000 voter challenges they went through, all were dismissed for various reasons.

He’s not sure if that will continue. But one thing that may continue is his struggle to hire enough workers. With the history of threats, the long hours, plus a competitive job market, election-season temps are hard to find.

“We’d order 25 employees to start on Monday. They’d come up with 12. Six of them would show up. And then by 5 p.m. on the first day, you had two,” Manifold said.

He started his own job two years ago. Today he says he’s the most senior of any elections leader in any of the four major Atlanta-area counties.

In May, Georgia expanded to all local governments a 2021 measure that made it illegal for election officials to accept outside funding such as grants. It came after Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg donated more than $400 million to election officials nationwide, which Republicans said could favor Democratic counties.

Manifold said these days, he does a lot of voter education. While voting systems are more reliable than ever, he said, “There’s just a lot of misinformation, and not understanding election processes. That’s probably the biggest concern.”

A state votes in a test of faith

At a job fair in a Baptist Church in Tucker, just east of Atlanta, Diona Holman 27, and Linda Watson, 73, walked past rows of tables. Jobs at the state prisons. Jobs at Waffle House. Jobs at local non-profits. The pair had clipboards in hand. They weren’t looking for employees, just voters.

They were canvassing for the Georgia Coalition for the People’s Agenda, which advocates for voting rights – asking people if their voter registrations were updated.

Most people they spoke to said they were registered. One woman said she didn’t vote. She didn’t explain why, but the look on her face said the reason ought to be obvious.

Merri Nance, a 63-year-old real estate agent, realized she needed to get her address updated after she moved. She said all the lawsuits, legislation and investigations have had an impact.

“In the last election, I was reminding people – don’t forget to vote. And people were so discouraged, they’re like, 'I’m not going to vote.' … They felt like it wasn’t going to make a difference.”

In July – 2? years after the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol and its fallout – a national USA TODAY/Suffolk University poll found that 7 out of 10 Americans agreed U.S. democracy is “imperiled.”

But Raffensperger believes those views are in the minority amid a Georgia system he says has strong security, voter confidence and accessibility. It’s never been easier to vote, he says.

A January AJC poll found that confidence was rebounding, with 73% of voters saying they thought elections were fair and accurate, compared with 56% of voters about a year earlier.

There was also a partisan gap. About 87% who identified themselves as liberals said they were confident, compared with 61% of conservatives.

Raffensperger said Trump’s efforts to sow doubts about election results likely diminished the number of Republicans voting for president in Georgia in 2020, which is why he believes that tactic will eventually wane.

“It may be a great way to raise money and run your hustle on people. But at the end of the day, it’s not a winning campaign strategy,” he said.

Political observers and scholars say what role Trump’s indictments play – whether they act as a turning point to a tumultuous era in Georgia elections, or deepen divides and the politicization of voting ? remains to be seen.

“There’s a chance it will make polarization worse,” Kreis said. “On the other hand, if people are forced to listen to the evidence and to contemplate what prosecutors are presenting, perhaps that will sway a considerable number of people.”

Yet the pressure and scrutiny on elections will continue in Georgia as long as it’s a swing state. That could mean more turnout or more disinformation. Or both.

In his office in the Capitol, where armed Trump supporters protested the former president’s election loss in 2020, Raffensperger says some people won’t ever change their minds.

“Some people today still have not and will not face and maybe cannot face the brutal truth of what happened in 2020. And that is, in Georgia, President Trump lost by about 12,000 votes,” he said.

He said he’s hopeful that political candidates with positive messages will emerge and leave behind “all this elections nonsense” and stop “looking at the referees and blaming them for all their shortcomings.”

“Honestly, I think most Georgians, most Americans have moved on. They’re tired of all the chattering class back there talking about what happened three years ago,” he said.

Outside his office, 2020 wasn’t going anywhere just yet.

Two days after Raffensperger spoke, Trump arrived back in Washington, D.C. – to appear as a defendant in federal court. That indictment, on charges of trying to overturn the election, was built in part around the phone call he made to Raffensperger.

Now, in the light of a late Georgia summer, in the eighth month of 2023, the year 2020 feels as present as ever. Witnesses in Fulton County said they had been summoned to testify Tuesday. Indictments could come as soon as immediately after.

And just down the street from Raffensperger’s office, the barricades and police wait, along with the rest of the state, for what comes next.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Trump indictment in Georgia: How 2020 forever changed its elections