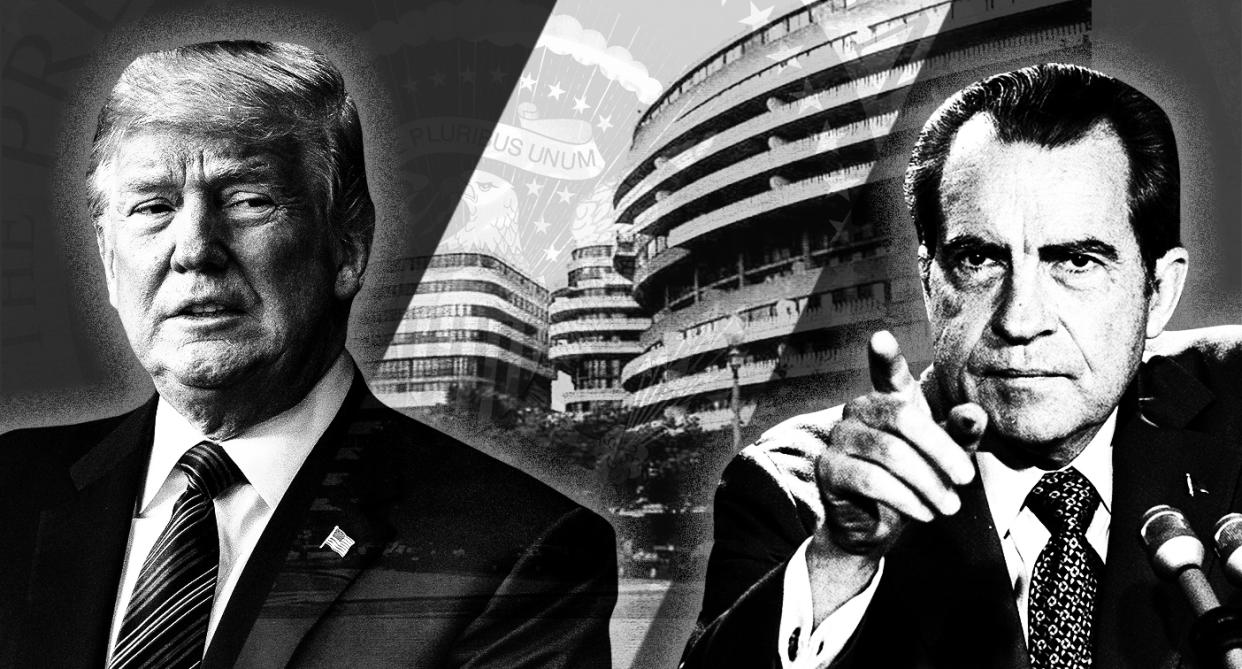

This time, it really is like Watergate — and Trump is making the same mistakes

So now the president’s campaign manager and his longtime henchman are likely going away for a while, with maybe a stop at the special counsel’s office first, and his White House lawyer has apparently spent hours with Robert Mueller’s prosecutors, detailing what it’s like to work for a boss who calls to rage at you through pieces of cheeseburger while lounging in bed like some cable-watching Caligula.

In terms of comic absurdity, we haven’t quite reached the point yet of Richard Nixon’s secretary contorting herself for the cameras, with admirable athleticism, to demonstrate how she managed to erase a critical White House tape by stepping on a pedal for 18? minutes without realizing it. But we’re definitely trending in that direction.

For almost a half century now, wannabe Woodwards and Bernsteins in my industry have been gleefully comparing every unflattering revelation to Watergate, without a shred of perspective. We went through Travelgate and Monicagate and Plamegate and a bunch of other gates I can’t remember now, all of which left entire generations of younger Americans confounded as to what we were even talking about.

The joke’s on us, though. Because now that there’s a growing crisis in the White House that really does eerily echo, in profound ways, the cataclysmic events of Nixon’s reelection campaign and his aborted second term, we don’t really have a way to do it justice.

As John A. Farrell, the author of a fair-minded and absolutely brilliant Richard Nixon biography published last year, put it to me this week: “By an exponential factor, this is the gate that really deserves to be a gate.”

It’s easy enough — and others have done it ably — to highlight the superficial similarities between this White House scandal and Watergate. The most glaring, perhaps, is that both were triggered by burglaries of the Democratic National Committee — one a classic black-bag job, the other digital.

Then, of course, you have the president firing top law enforcement officials, calling the investigation a “witch hunt” and criticizing its scope. You have presidential lawyers — John Dean then, Michael Cohen now — cutting deals with prosecutors and threatening to turn on their former clients.

Just to make things more surreal, Trump this week derided Dean, a frequent critic of his, as a “RAT,” making Trump the first American president to take the position that White House aides paid by the public are bound by the blood oath of La Cosa Nostra.

But like I said, that’s all just surface stuff. The more remarkable and consequential parallel lies several levels deeper, I think, in a dark seam of self-delusion.

As Farrell points out in his book, Nixon had several opportunities, at least, to save his presidency by facing up to his own culpability and excising what came to be known — thanks to Dean’s talent for imagery — as the cancer on his presidency.

Right from the start, after the bungled break-in, he could have cut loose the perpetrators and cast himself as criminally out of touch, rather than the actual criminal he became. G. Gordon Liddy, the addled leader of the gang, volunteered to take the fall.

Other sordid details of illegal operations would likely have come to light soon enough, and Nixon would have had some more explaining to do. But a feigned combination of contrition and cluelessness, of which Nixon had proved more than capable in his career, would have spared him the worst.

There were other junctures along the way where Nixon could have taken responsibility and possibly saved his presidency, though the political costs of doing so kept going up. “Even if he’d lost the 1972 election,” Farrell told me, “he would have gone down as a reasonably great president with a flawed and controversial ending.”

Why couldn’t Nixon, legendary as a strategist, see the only way out? Because he was blindingly paranoid and resentful. A poor kid without much social grace or a topflight education, he’d spent a lifetime feeling belittled by the Ivy League types who were now trying to take him down.

Nixon felt at war with the media, the intelligence agencies, the urban liberals — to the point where he couldn’t find any fault of his own that he didn’t think his enemies had manufactured or magnified in order to kill him. Every new revelation of his own moral failure drove Nixon deeper into the bunker of his aggrievement, where ultimately he became trapped.

Late in his life, Farrell writes, Nixon would acknowledge that he took ill-advised risks in his career because it was how he had learned to beat competitors who had all the advantages he didn’t. As he explained it to an aide, “You continue to walk on the edge of the precipice because over the years you have become fascinated by how close to the edge you can walk without losing your balance.”

And then, of course, he fell.

Trump isn’t the son of a failed lemon farmer — far from it. Nor is he anything like the statesman that Nixon willed himself to become.

But Trump’s own formative experience — as a small-time, outer-borough developer trying to break into the haughty world of upper-crust Manhattan, as a showman and self-promoter shunned by the big banks and respectable media titans whose approval he craved — has left a Nixonian crater in his psyche.

He too is an addictive risk taker who seems always to be testing gravity, because only on that precipice of ruin can he feel stronger and more deserving than the critics who sneer at him.

Trump, like Nixon, could have turned this whole thing around right at the outset. He could have marched out and condemned the Russians for interfering in our politics, as he should have. He could have lambasted Paul Manafort and Michael Flynn and their whole B-movie gang for acting as agents for a foreign regime.

Sure, there would have been some uncomfortable revelations, like the meeting Don Jr. took to see if the Russians had anything worth committing treason for. (They didn’t, so it’s all good.) Chances are, though, had Trump shaken his head sadly and claimed to have been out of touch and vowed to cooperate with investigators, the worst peril would have passed.

But Trump is at war with the many-tentacled establishment. He was never going to give us the satisfaction of seeing him express remorse. He was never going to aid us in questioning the legitimacy of his election.

He’s going to bluster his way out. He’s going to bully and rage and lie.

As I’ve said before, and I may well be wrong, I doubt we’ll ever see evidence that Trump himself covertly colluded with the Russians. They knew enough about Trump to know that his winning would be a coup for them; nobody at the Kremlin needed any incentivizing there. And if Trump felt the need for a backchannel to the Russians, he wouldn’t have publicly begged for their help.

But that’s not Trump’s problem now. Rather, it’s the ammunition he’s given his adversaries by trying to influence the investigation, the impetus he’s given his own aides to save themselves. With every new revelation, he grows more defiant and inches ever closer to the breach.

Maybe Trump believes, as some of his critics do, that today’s Republicans are too feckless to hold him accountable. But as my colleague Jonathan Darman reminded us in this piece a few months back, Republicans stood by Nixon right up until the final stage of his politically fatal illness in 1974.

It was only when the evidence surfaced in the form of tapes, when the incontrovertible proof of Nixon’s petty criminality was there for all to hear, that his own party left him for dead. It was only then that he became an unbearable political liability, as opposed to a moral one.

“I don’t think he should ever be forgiven,” no less a Republican than Barry Goldwater said of Nixon, shortly after the fall. “He came as close to destroying America as any man in that office has ever done.”

By the time all this is over, that’s a statement Goldwater’s successors may want to revisit.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: