The Last 100 Days: How much does saying ‘radical Islamic terrorism’ matter?

Ever since the administration of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, presidents have been judged on the successes they notch during their first 100 days. Now, as Barack Obama prepares to end his historic turn on the political stage, Yahoo News is running The Last 100 Days, a look at what Obama achieved during his consequential presidency, how he navigates the struggles of his last months in office and what lies ahead for him after eight years filled with firsts. We will also look at how the country bids farewell to its first African-American president.

It’s not a literal 100 days — Obama leaves office in late January 2017.

And it won’t all be about policy. As Obama himself is fond of noting, he also spent his two terms as father to daughters Malia and Sasha and husband to first lady Michelle Obama. And even without much input from the White House, the cultural landscape shifted dramatically over his two terms on issues such as gay rights.

And then there’s the way the president sees the presidency — not just his tumultuous years at 1600 Pennsylvania Ave., but also the institution and its relationships (for better or worse) with other branches of government and with the news media.

In this 13th installment, we look at Obama’s war on terrorism rhetoric and his refusal to say that the enemy is “radical Islamic terrorism.”

_____

President Obama does not talk about “radical Islamic terrorists” when discussing the war on the so-called Islamic State. He generally avoids the expression “war on terrorism.” And earlier this year, he went on something of an epic rant against Republicans who charge that those rhetorical choices show him to be na?ve or politically correct.

“There has not been a moment in my 7 1/2 years as president where we have not been able to pursue a strategy because we didn’t use the label ‘radical Islam,’” he said in June after a national security meeting at the White House. “Not once has an adviser of mine said, ‘Man, if we really use that phrase, we’re going to turn this whole thing around.’ Not once.”

The president continued, “Calling a threat by a different name does not make it go away. This is a political distraction.”

Every schoolchild knows the mantra that “actions speak louder than words.” But the debate over how presidents frame the motives, means and goals of post-9/11 campaigns against extremists is not a sterile, inside-the-Beltway argument, or merely a fight for an edge in the political arena.

How the president talks about terrorism is literally a matter of life and death.

The Republican-led Congress has refused for nearly two years to debate and vote on Obama’s “Authorization for Use of Military Force” (AUMF) against the so-called Islamic State. The president’s draft AUMF would retroactively bless his undeclared but escalating war on the group as well as loosely defined “associated forces.” How Obama’s successor will describe those forces — by name, geography, allegiances, tactics or goals — and define victory will determine how, when and where American troops next plunge into battle.

Obama was responding directly to Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump, but many of his GOP critics have accused the Democratic president of being rhetorically soft on terrorism.

In the aftermath of the Brussels attacks in March, Trump had suggested on NBC’s “Today” that his own rhetoric on terrorism, including his call for a halt to Muslim immigration and tourism to the United States, was “why I’m probably No. 1 in the polls.”

He may not have been wrong about the link to his Republican primary success. A February 2016 poll by the nonpartisan Pew Research Center found that 65 percent of Republicans and independents who lean toward the GOP wanted the next president to “speak bluntly even if critical of Islam as a whole.” For Democrats and independents who lean left, it was just 22 percent.

Another Pew poll from September 2014 found that 50 percent of Americans say Islam is more likely than other religions to encourage violence by its followers, the highest level since 2002. That was up from 43 percent in July and 38 percent in February, roughly tracking with the Islamic State’s military gains and its use of graphically violent videos, including some showing the beheading of Americans.

“Whether you call it radical jihadism or radical Islamism, I’m happy to say either. I think they mean the same thing,” Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton said on CNN June 14. “It mattered we got (Osama) bin Laden, not what name we called him.”

Some Republicans dismiss the debate as a shallow substitute for serious discussion. “Are [some Republican critics] under the impression that an American missile kills you differently if the president has called you an ‘Islamist terrorist’?” one former senior national security aide to George W. Bush told Yahoo News in early 2015. The official, who requested anonymity to speak frankly, complained that the media doesn’t give enough attention to substantive criticisms about how Obama has handled world affairs. “Instead of talking about chaos in Libya, you’re copy editing your way through foreign policy.”

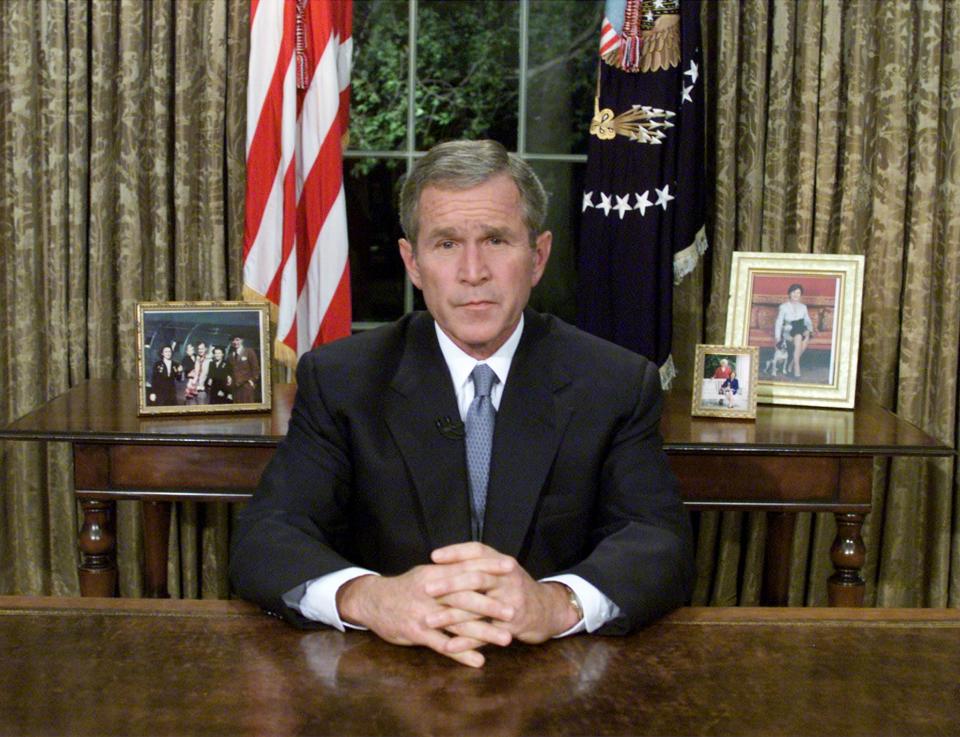

But the president’s critics pointedly contrast what they consider Obama’s overly careful parsing with George W. Bush’s blunter language. The night of the 9/11 attacks, Bush declared a “war against terrorism.” Two weeks later, he promised Americans that “our cause is just and our ultimate victory is assured.” He announced that he wanted Osama bin Laden “dead or alive” and declared victory in Iraq aboard an aircraft carrier, in front of a giant “Mission Accomplished” banner. He twice characterized the global conflict against terrorists as a “crusade,” a bland term in the West that remains loaded for Middle Eastern Muslims. Some of his rhetoric felt drawn from the Bible’s moral universe, pitting America against “evildoers.” And there were no shades of gray, he warned repeatedly: “Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists.”

Bush later expressed regret for much of that blustery talk. Aides said first lady Laura Bush rebuked him for his “dead or alive” comment almost immediately after he made it, and they described him as annoyed with himself for not thinking through the ramifications of using “crusade” to describe the conflict.

“Some of my rhetoric has been a mistake, “ Bush said in a January 2009 press conference that doubled as an exit interview of sorts.

Bush supporters and critics who recall his rhetoric as an uncompromising war on nuance get it wrong. He made no mention of Islam when he declared “war against terrorism” on 9/11. Less than one week later, he made a high-profile visit to the Islamic Center in Washington to state categorically that al-Qaida did not represent Islam — a message aimed at nervous Muslim allies overseas and a domestic audience that, his aides worried, might include some misguided souls looking for payback at home.

“The terrorists are traitors to their own faith, trying, in effect, to hijack Islam itself,” Bush said. “The enemy of America is not our many Muslim friends; it is not our many Arab friends. Our enemy is a radical network of terrorists and every government that supports them.”

Those words launched a yearslong effort to separate al-Qaida from Islam in the public consciousness.

For a brief stretch in 2006, Bush started to refer publicly to “Islamic radicals” or “Islamic fascists.” While the term was broadly popular at the time among a segment of the conservative commentariat, it appears to have originated in a 1979 article in the Washington Post. In that piece, an anonymous State Department official in the Carter administration wondered whether the Iranian Revolution was sweeping an “Islamist fascist” to power.

Bush’s new message was poorly received in the Middle East. Saudi Arabia’s cabinet declared one week later that the expression was wrong because “terrorism has no religion or nationality.” The “Islamic fascist” comments dwindled to a trickle.

And there were times when Bush was accused of the kind of political correctness that Trump accuses Obama of today. It happened in August 2004, for example, when he suggested that his administration had misnamed the “war on terror.”

“It ought to be ‘the struggle against ideological extremists who do not believe in free societies and who happen to use terror as a weapon to try to shake the conscience of the free world,’” he said in a speech. He was mocked, notably in the news media. He went back to “war on terrorism.”

There were other rhetorical adjustments. The war in Afghanistan briefly carried the name “Operation Infinite Justice,” which was quickly scrapped because many Muslims believe only God can dispense “infinite justice.” And “Operation Iraq Liberation” lasted only a moment before officials realized that they did not want a war for OIL. Perhaps still angry with himself over the “crusade” controversy, Bush in June 2004 trimmed Dwight D. Eisenhower’s famous D-Day message to leave out a reference to “the great crusade” of defeating Nazi Germany.

Even more interesting was a moment of politically ill-advised candor and nuance from Bush at the height of his reelection fight. In August 2004, on NBC’s “Today Show,” Bush was asked whether the United States could ever win the global war on terrorism.

“I don’t think you can win it,” he replied. “I think you can create conditions so that those who use terror as a tool are less acceptable in parts of the world.”

Democrats quickly seized the political opening, and Bush quickly retreated.

The same drama played out, but in reverse, a couple of months later. Democratic nominee (and future Obama secretary of state) John Kerry told the New York Times that victory in the war on terrorism meant reaching a point “where terrorists are not the focus of our lives, but they’re a nuisance.”

“I know we’re never going to end prostitution. We’re never going to end illegal gambling,” the former prosecutor told the Times. “But we’re going to reduce it, organized crime, to a level where it isn’t on the rise. It isn’t threatening people’s lives every day, and fundamentally, it’s something that you continue to fight, but it’s not threatening the fabric of your life.”

Cue Republican onslaught, and candidate retreat.

Ten years later, it was Obama’s turn to serve gray to an audience hungry for black and white. At a Sept. 3, 2014, press conference with Estonia’s president, Obama said a U.S-coalition could reduce the Islamic State “to the point where it is a manageable problem.”

He had previously promised to “degrade and destroy” the rampaging death cult, which is also known as ISIS. Republicans accused him of sending a mixed message.

One of Obama’s fiercest Republican critics, Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas, has channeled Bush’s blunter side and demanded that the president lead America to “victory over evil” and that ISIS to be “utterly destroyed.”

Obama aides express frustration at the notion that the United States can wipe out every last ISIS adherent. They are also mindful that yesterday’s boast can come back to haunt them, the way Obama’s confident reelection campaign message that “al-Qaida is on the run” did after extremists assaulted U.S. facilities in Benghazi in September 2012, killing four Americans.

While Obama had used the phrased “war on terrorism” during his history-making 2008 campaign, he played down the phrase once in office, arguing that you can’t win a war against a tactic. In March of 2009, the the Washington Post reported that the White House’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB) had directed other agencies to abandon the term in favor of the bureaucrat-speak “overseas contingency operations.” The Pentagon quickly denied the report. So did the OMG director. An OMB spokesman blamed the proposal on an “overexuberant” midlevel bureaucrat.

“We always tried to define the enemy as organizations,” Deputy National Security Adviser Ben Rhodes told Yahoo News in a telephone interview. “We made sure to say ‘al-Qaida,’ “al-Shabaab,’ rather than an ideology or a tactic.”

But at the 2015 National Prayer Breakfast, Obama touched off controversy by invoking ties between Christianity and the Crusades, the Inquisition, slavery and Jim Crow — saying that no one religion has a monopoly on violence. He added a layer of controversy by saying the Jews killed at the kosher supermarket in Paris were “randomly” slain. Aides initially stuck to their guns, then recanted.

Conservatives denounced Obama’s reference to the Crusades as outdated and an inappropriate moral equivalence. The intensity of the response surprised the White House.

“There’s a set of words, it’s almost as if they’re given a card — a do-not-speak card,” Ted Cruz once said at the conservative Center for Security Policy think thank. “The words ‘radical Islamic terrorism’ do not come out of the president’s mouth. The word ‘jihad’ does not come out of the president’s mouth. And that is dangerous.”

Obama has, at times, taken aim at “radical Islam.”

In a July 2010 interview with the South African Broadcasting Corp., Obama was asked whether it was to blame for instability.

“What you have seen in terms of radical Islam is an approach that says that any efforts to modernize, any efforts to provide basic human rights, any efforts to democratize are somehow anti-Islam,” Obama responded. “And I think that is absolutely wrong.”

And in a January 2016 press conference with British Prime Minister David Cameron, Obama tied home-grown terrorist attacks directly back to domestic Muslim populations.

“The United States has one big advantage in this whole process,” Obama said in little-noticed remarks. America’s approach to immigration and assimilation means U.S. Muslims “feel themselves to be Americans” while the same is not true in Europe.

“That’s probably the greatest danger that Europe faces,” the president said. Europe is too quick to fall back on “a hammer and law enforcement and military approaches,” he said. “There also has to be a recognition that the stronger the ties of a North African, or a Frenchman of North African descent to French values, French Republic, a sense of opportunity — that’s going to be as important, if not more important, over time in solving this problem.”

Obama will hand his successor “this problem” — terrorist groups with global reach — as surely as the next president will inherit the campaign against ISIS and the war in Afghanistan. No matter what they’re called.

Obama has had other awkward moments when discussing terrorism. There was the January 2014 interview in which he dismissed ISIS as “a JV team.” Fact-checkers have knocked down White House aides’ claims that he was not talking about the Islamic State. There was the November 2015 press conference where a CNN reporter channeled American fears of ISIS and asked, “Why can’t we take out these bastards?” — a question some Obama aides and allies mock to this day, while others see a lesson about the president not being in tune with the popular mood.

Asked whether Obama regretted any of his rhetoric about terrorism, Rhodes demurred. But the aide warned the next commander in chief to be cautious with words. “If you define the enemy in existential terms, people are going to expect you to resource your approach accordingly,” Rhodes said. “It they (ISIS) were an existential threat, really, we would have tens of thousands of troops going towards Raqqa,” the group’s self-styled capital.

Rhodes cautioned the next president not to get swept up by “intense pressure” to fuel the national mood, and “overpromise” what can be done about a given threat. “You’re on the hook for whatever you say,” he said.

“We always felt it was better to be criticized for not being strident,” Rhodes told Yahoo News. “Better that than promise something you’re not going to deliver.”