The Supreme Court just ruled on Native American adoptions: Why it's a big deal

In big news for families, the U.S. Supreme Court has upheld the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA), letting tribal families keep their preference in adoption cases involving Native American children.

A white couple challenged the law. Jennifer and Chad Brackeen, adoptive parents of a young citizen of the Navajo Nation, claimed that ICWA is “racially discriminatory.”

The Court upheld the 1978 law, ruling against the Brackeens, in a 7-2 vote on June 15.

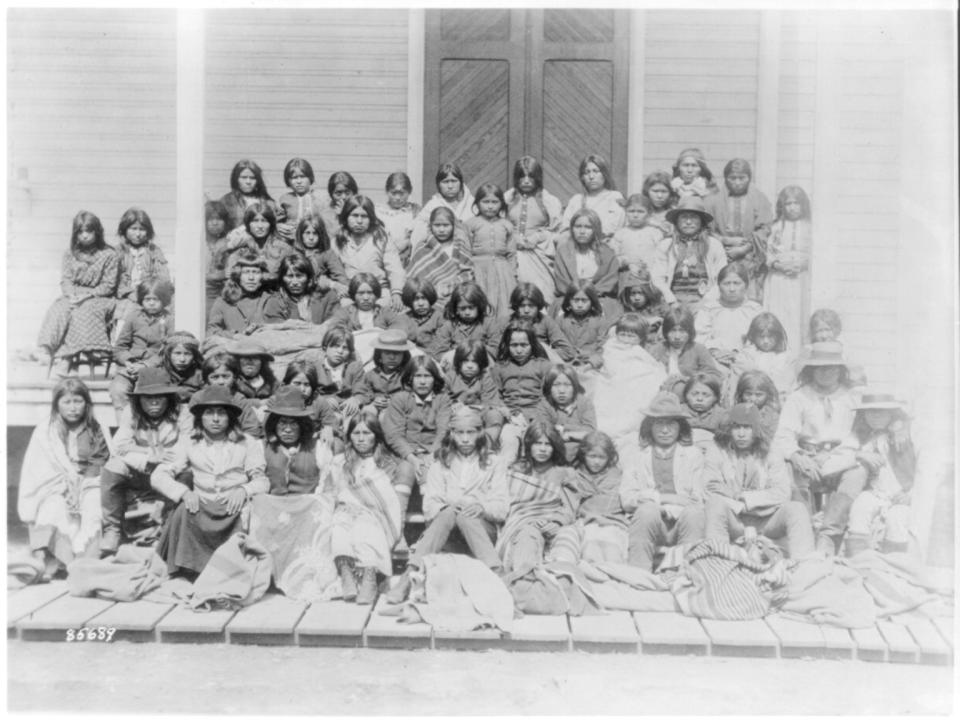

The 1978 law ended a government-mandated tradition of taking Indigenous children from their homes and placing them in non-Indian families and boarding schools.

"Our Nation’s painful history looms large over today’s decision," President Joe Biden said in a statement published by the White House. "In the not-so-distant past, Native children were stolen from the arms of the people who loved them. They were sent to boarding schools or to be raised by non-Indian families — all with the aim of erasing who they are as Native people and tribal citizens. These were acts of unspeakable cruelty that affected generations of Native children and threatened the very survival of Tribal Nations. The Indian Child Welfare Act was our Nation’s promise: never again."

Jasmine Grika, 32, is one of the children who grew up under ICWA's protection.

“I’d like to think it was a win ... but I can only wonder if we can ever take off our armor and truly feel and be protected under the law,” she tells TODAY.com.

As a citizen of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe who is Tribally Affiliated with Red Lake Nation, she was placed with two foster families before being adopted by a White Earth Ojibwe mother and a Jewish father at age 10.

"It's a momentous and celebratory moment, and after digesting it, I sat there holding the tension and questioning why it had to happen in the first place," says Grika, now a nonprofit associate in Minneapolis. "So much energy, effort, time and resources went into this case to fight and prove that tribes retain inherent sovereignty over their children, families, and communities."

The Brackeen family, who are at the heart of the Supreme Court case, have been trying to adopt the younger half-sister of the Native American son they already adopted.

Matthew D. McGill, an attorney for the Brackeens, tells TODAY.com in an email, “Our main concern is what today’s decision means for the little girl, Y.R.J. — now 5 years old — who has been a part of the Brackeen family for nearly her whole life. The Court did not address our core claim that ICWA impermissibly discriminates against Native American children and families that wish to adopt them, saying it must be brought in state court .... we will ask the state court to address it in the Brackeens’ upcoming trial to adopt Y.R.J.”

The child who was adopted out of her culture

Leslee Lovato-Romero, who was adopted as a newborn in 1971 by a couple in Colorado, always wanted to meet her mom.

Her new family was open about her adoption story and supported a potential future relationship with her birth parents. However, Lovato-Romero barely knew anything about her background — she learned eventually that her birth mother is Northern Arapaho and her birth father is Sicangu Lakota.

"My parents said my biological mother was alone at the time of my birth and they knew very little about my father," Lovato-Romero, 51, told TODAY.com.

Later, at the University of Colorado at Boulder, a law school clinic helped locate her birth certificate and the Catholic social services agency involved in her adoption.

"A caseworker told me my mother died in 1977," she said. "It was traumatic — my mother was a living, breathing person in my mind who I was going to meet someday. Now, I would never do it."

Lovato-Romero was one of the lucky ones. She grew up in a loving family. But like generations of Native American children placed for adoption or stripped from their birth parents, she also grew up without any understanding of her cultural heritage and traditions.

When she was 24, Lovato-Romero found her biological father on the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota. She called him and delivered a long-rehearsed speech: "I know you didn’t know I existed ... I don’t want anything from you but if you want to know me, I’m open to that.”

Her father — who hadn’t known about the adoption or the pregnancy — agreed. "I know you're my daughter," he said. "I have always felt something was missing and now I found it."

The Supreme Court gets involved

The Supreme Court case focused on a provision in the law that gives tribal members preference in adoption proceedings. At issue is this question: Is such preference based on race or a tribe’s political status?

ICWA (pronounced ICK-wa) was passed in 1978 to keep Native American children with their own families when possible, ending a longstanding government practice of removing them and placing them in boarding schools or in the homes of white Christian families. For decades before 1978, Indian families were often discriminated against for living in small, multi-generational homes without plumbing or electricity. Even now, Native American families are four times more likely to have their kids removed and placed in foster care than white families, according to the National Indian Child Welfare Association, a non-profit organization that supports Native American children.

“Ironically, tribes that were forced onto reservations at gunpoint are now being told that they live in a place unfit for raising their own children,” the Indian Family Defense, a bulletin of the Association on American Indian Affairs, stated in 1974.

“Being white or Christian was the standard of good parenting and poverty was somehow equated to bad parenting,” Kimberly Cluff, the legal director for the California Tribal Families Coalition, told TODAY.com.

The white couple who adopted a Navajo child

In a 2019 interview with Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton that was published on his official state YouTube channel, the Brackeens, who have two biological children, explained that three years prior they fostered an infant named Zachary.

“We fell in love with him right away,” said Jennifer.

When Zachary’s parents’ rights were terminated, the Brackeens still couldn’t adopt him. They said they faced this roadblock because ICWA gives a child’s extended family, other tribal members or other Indian families preference when considering foster and adoptive placement.

According to a 2019 petition, placement with a Navajo family in New Mexico “ultimately failed to materialize” and in 2018, the Brackeens successfully petitioned to adopt Zachary. The Brackeens now want to adopt Zachary’s younger half-sister.

Meanwhile, the defendants in the Supreme Court case — the Cherokee Nation, Morongo Band of Mission Indians, Oneida Nation and Quinault Indian Nation — argued that ICWA is based on a tribe’s political status as a sovereign nation, not on race. The Biden administration also is defending the law in court.

Dan Lewerenz, an assistant professor at the University of North Dakota School of Law and an attorney with the Native American Rights Fund, said the law does not prohibit white parents from adopting Indian kids; instead, the law ensures that Indian parents and families get a chance.

“Placing an Indian child with (extended) family isn’t a mandate,” said Lewerenz, a member of the Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska. “It’s preference in the absence of good cause to the contrary. Judges are supposed to take the child’s best interest into consideration, which is an individualized determination.”

A dark history

ICWA arose from a painful history.

For centuries in the United States and Canada, Indigenous children were taken from their parents and forced into government or church-run boarding schools “in the pursuit of a policy of cultural assimilation that coincided with Indian territorial dispossession,” according to a 2022 report from the U.S. Department of Indian Affairs. Indigenous parents were also forced to give their children to government officials, who placed them in the child welfare system, usually for adoption by non-Indigenous families, according to a 1977 Senate hearing on ICWA.

Students’ names were changed to sound English, their hair was cut and they were banned from speaking their languages and practicing cultural traditions, according to the 2022 report. Children performed manual labor and were punished with starvation, beatings, whipping and solitary confinement, the report says; living in overcrowded conditions, sometimes with three children sleeping in one bed, kids were sexually abused and denied health care and basic necessities like soap.

Some students who died under these conditions were placed in burial sites — sometimes unmarked — on school grounds, the 2022 report said.

While introducing the Indian Child Welfare Act in 1977, Sen. James Abourezk cited research by the Association of American Indian Affairs showing that “a minimum of 25 percent of all Indian children are either in foster homes, adoptive homes, and/or boarding schools, against the best interest of families and Indian communities.”

“ICWA isn’t saying that white people shouldn’t adopt,” Cluff said. “But rather, children generally do better in their communities.”

An adopted child who grew up with her culture

Jasmine Grika agrees.

“My (adoptive) mom immersed me in every cultural activity,” said Grika of the White Earth Ojibwe woman who adopted her at age 10.

“Outside of being welcomed back to the circle with my Jingle Dress dance (a healing dance performed at powwows), I attended sweat lodges, which for me, is a deep cleanse to connect with myself, the creator and Mother Earth to find clarity and centering,” said Grika, Grika, a citizen of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe who is Tribally Affiliated with Red Lake Nation. “I also learned about the four sacred medicines (sage, sweetgrass, tobacco and cedar) and the significance behind them.”

Grika’s mom also taught her to sew. “She inspired me with her creativity when it came to textiles and ribbon skirts,” she recalled. “Her designs often carry a story.”

“I live these values every day and they influence how I show up as a human,” said Grika. “I am really grateful.”

Forging a bond with a long-lost father

Lovato-Romero, who never did get to meet her birth mother, had a legal right to her birth records and was able to find her birth father thanks to ICWA. Although she only knew him for seven years before his 2005 death, they built important memories together.

Two weeks after talking to her biological father on the phone, Lovato-Romero, her then-2-year-old daughter and her adoptive mother drove from Colorado to South Dakota to spend the weekend with him.

“He was about my height with jet-black long hair that he wore in a ponytail,” recalled Lovato-Romero. “We had the same hands. ...

“He said, ‘Had I known about you, you would have lived with me.’ The Lakota side of the family strongly believes that children are a culture’s most precious asset.”

The father grew closer to his daughter and two grandchildren, giving Lovato-Romero her official Indian name, she said: “woman who looks for her people, or Oyate Okele Win.”

“Knowing who you are and where you come from is centering,” she said. “It’s been an immensely important part of my life, and my children were able to grow up knowing their family, culture and traditions.”

This article was originally published on TODAY.com