Students are increasingly refusing to go to school. It’s becoming a mental health crisis.

The police were in her driveway. They wanted her son.

Jayne Demsky’s teenage son was not a criminal. He never stole, used illegal substances, or physically hurt anyone. He just didn’t go to school.

It started in the middle of 6th grade when he began staying home from school on days his anxiety was too difficult to manage. Those days became more frequent, turning into weeks and months, until he stopped going altogether. Now an officer was at her house, waiting to take her son to school.

“I would describe it as hell,” said the mother from Mahwah, New Jersey, who recalled feeling hopeless and constantly "on the verge of an emotional breakdown."

Demsky sought help from educators, doctors and counselors, trying to understand what was stopping her son from going to school for nearly a year. Finally, a psychiatrist told Demsky about a condition that affects a growing number of students with severe anxiety: school avoidance.

“It was almost like a revelation,” she told USA TODAY.

School avoidant behavior, also called school refusal, is when a school-age child refuses to attend school or has difficulty being in school for the entire day. Several mental health experts told USA TODAY it has become a crisis that has gotten worse since the COVID-19 pandemic.

"There's no book on this, it's not spoken about," said Demsky, whose son declined to be interviewed by USA TODAY but gave his mother permission to share their story. "It's very scary and parents feel a sense of helplessness."

The two continued to struggle with school avoidance for four years with little guidance. In 2014, she created a website to offer families the help and support she couldn't find. The site eventually turned into the School Avoidance Alliance, which spreads awareness and educates learning facilities and families of school avoidant children.

School avoidance is not a concrete diagnosis and looks different in every child. Some students consistently miss a couple of days a week, while others may leave during the day or escape to the nurse or counselor’s office. In some extreme cases, students don't step foot in a school for months or years at a time.

Half a dozen family members and students told USA TODAY that school avoidance has affected not only their mental health, often leading to anxiety and depression, but also their family dynamics, relationships with fellow students, and grades. It has threatened their prospects of graduation and a thriving future.

School avoidance is a complicated condition that neither parents nor school systems are fully equipped to handle. Some experts say school systems and national organizations are beginning to come up with strategies to get kids back to school, while others wonder if there's a better answer.

"Our waiting list is like 180 families right now," said Jonathan Dalton, a licensed psychologist who runs the Center for Anxiety and Behavioral Change in Maryland and Virginia, which offers treatment to those affected by anxiety and other related disorders, including school avoidance. "The mental health infrastructure was never designed for this level of need."

‘Anxiety and avoidance are teammates’

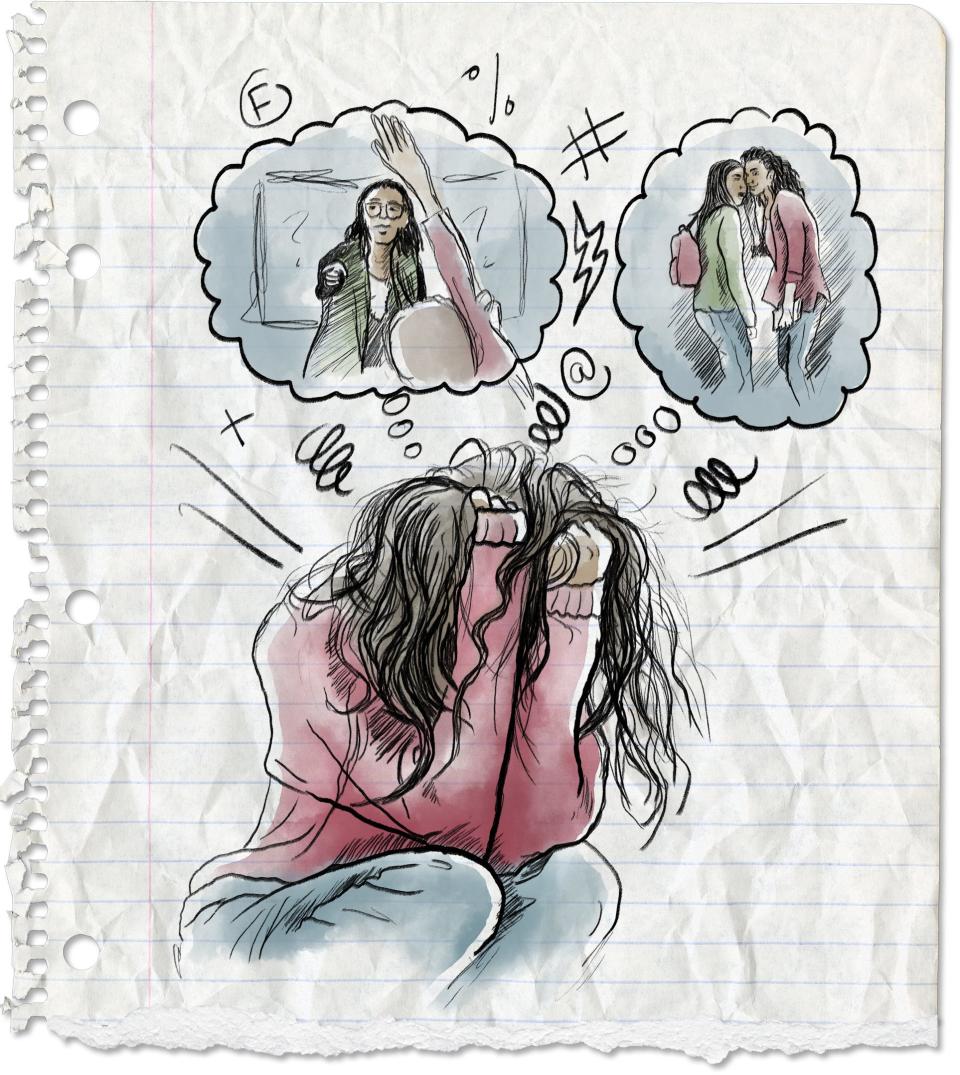

In the passenger seat of her mother’s car, Anna saw the school slowly peek above the horizon. Her heart began racing, her body shaking. Her breathing grew shallow and fast. And then, the unmistakable sign of her panic attacks: her hand smacking her leg.

“It’s scary because it’s not voluntary at all. It’s just kind of happening to you,” said Anna, a Virginia college student who spoke on the condition that she not be fully named because of mental health stigma. “I’ll sit in the car and tell myself to go in, but my body won’t carry me inside.”

Anna, who was school-avoidant in 10th grade, said her school avoidance began spiraling after she recovered from a medical condition. Despite getting better, she hadn't been to school in a month, and the mere thought of returning generated anxiety.

For most students, mental health experts say, school avoidance is typically a symptom of a bigger problem: anxiety.

“Anxiety and avoidance are teammates because they work on the same function,” Dalton said. “Kids feel very uncomfortable when they go to school or think about going to school, so they do what evolution teaches them to do and avoid something that makes them scared.”

Anxiety may be a common thread, but the basis of that fear varies with each student, said R. Meredith Elkins, program co-director of the McLean Anxiety Mastery Program at McLean Hospital in Massachusetts.

School avoidant behaviors most often occur in the transition between elementary, middle school and high school, she said.

“In younger children, we’re more likely to see school avoidance motivated by separation anxiety,” Elkins said. “As kids get older and their social environment changes, the way they interact with peers becomes important, and we see social anxiety as a more frequent contributor.”

School avoidance also tends to be a gradual process – starting with missing a day or two, then missing a week until the student becomes school avoidant altogether. The longer a student is away from school, the harder it is to get them back into school, and it can affect other aspects of their life, like relationships and work opportunities, Dalton said.

“We don’t call it work refusal, we call it unemployment,” he said. “If (students avoid school) and gain short-term relief, they’ll become a master of avoidance, and that doesn’t play well for the future.”

‘This is a crisis,’ and COVID made school avoidance worse

Some research suggests as few as 1% of students are school avoidant, while organizations like the School Avoidance Alliance estimate 5% to 28% of students in the country exhibit school avoidant behaviors at some point in their lives.

“How (school avoidance) is defined is nebulous,” Dalton said. “Different organizations use different language and criteria to describe it.”

Though it’s unclear how many students are affected, mental health experts agree the problem has gotten significantly worse since the COVID-19 pandemic. As schools began reintegrating in-person learning, many students didn’t return to the classroom.

In some cases, the pandemic halted the progress of many school avoidant students who were making a slow reentry. In other cases, experts said, the pandemic accelerated school refusal.

“We saw a larger shift in kids who were on the cusp before and then after COVID started refusing completely,” said Krystina Dawson, a school psychologist and mental health supervisor in Fairfield County, Connecticut. “Once the pandemic hit and we introduced remote learning, kids got comfortable in their homes.”

School refusal cases may have also grown as students report experiencing anxiety at record levels. A Kaiser Family Foundation analysis found adolescents experiencing anxiety or depression increased by one-third from 2016 to 2020. The same report also found access to mental health services worsened during the pandemic.

“A lot of school refusers, when March 2020 happened, they were like, ‘Welcome to my world,’” Dalton said. “This was these kids’ lives.”

Experts say it has been more difficult to get students to return to school as they become accustomed to learning and socializing virtually. Some parents are more likely to be home throughout the day working remotely, which makes it easier for school avoidant children to stay home.

“The family dynamics have changed,” Dawson said. “Sometimes now there is one parent staying at home, which can be enticing for a child.”

‘Unless you've been through it, you don’t understand’

Katherine and her son Peter started nearly every morning crying together in the school parking lot. The tears were hot and flowing.

They always drove to the building with hopes he would make inside. But eventually the pair headed home, longing the next day would be better.

His school avoidance peaked in 2021 during seventh grade. Katherine, who who lives just outside Boston, spoke on the condition that she not be fully identified because of the stigma associated with mental health.

Katherine identified her son’s affliction after a Google search led her to the School Avoidance Alliance, where she educated herself and found solidarity in the organization's Facebook group. But she still found little empathy or understanding among friends, family and peers, she said.

Her son would say, "‘I just want to be normal.’ It was heartbreaking,” she told USA TODAY. “As a parent, it is so isolating. It is so lonely because unless you’ve been through it, you don’t understand.”

The family struggled for years to find the origin of Peter’s anxiety until he was finally diagnosed with pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome, or PANS, which is a sudden onset of neuropsychiatric symptoms typically linked to an infection, according to Nemours Children’s Health.

With the help of treatment and counseling, Peter is now a freshman in high school and goes to school most days. Katherine was able to secure an individualized education plan for her son, but others are not so lucky.

“There’s shame, blame, and parents also don’t know how to deal with the schools,” Demsky said. “It’s a huge maze.”

Some educators don't take school avoidance seriously, families told USA TODAY. Schools sometimes threaten students' graduation or take students to family court.

The students who spoke to USA TODAY said that while they know some educators may view them as truant or misbehaving, they understand they’re missing educational milestones and experiences, and they want to return to school. But many of the schools’ solutions seem to only fuel their depression and anxiety.

"We had the resources, and it was still incredibly difficult" to treat Peter's school avoidance, Katherine said. "That's just not OK."

‘Avoidance ruins lives’

Educators and psychologists say the goal for every case of school avoidance is to get the child back into class.

It’s important for students to stop using avoidance as a coping strategy before it becomes their primary way of dealing with problems for the rest for their lives, Dalton said.

“I don’t treat anxiety. I don’t have to treat anxiety because anxiety is temporary and harmless,” Dalton said. “What I treat is avoidance, and avoidance ruin lives.”

Others also argue returning to in-person class is important for social development.

“You’re increasing the diversity of exposure to social interactions that is difficult to replicate at home because there are some things that are uncontrolled at school that benefits your social development,” said Na’im Madyun, a school psychologist at Prince George County Public Schools in Maryland. “You’re more informed about how to navigate those nuances when you develop.”

But there’s no standard guidance how how to get kids back in the classroom, which leaves school officials to come up with their own solutions.

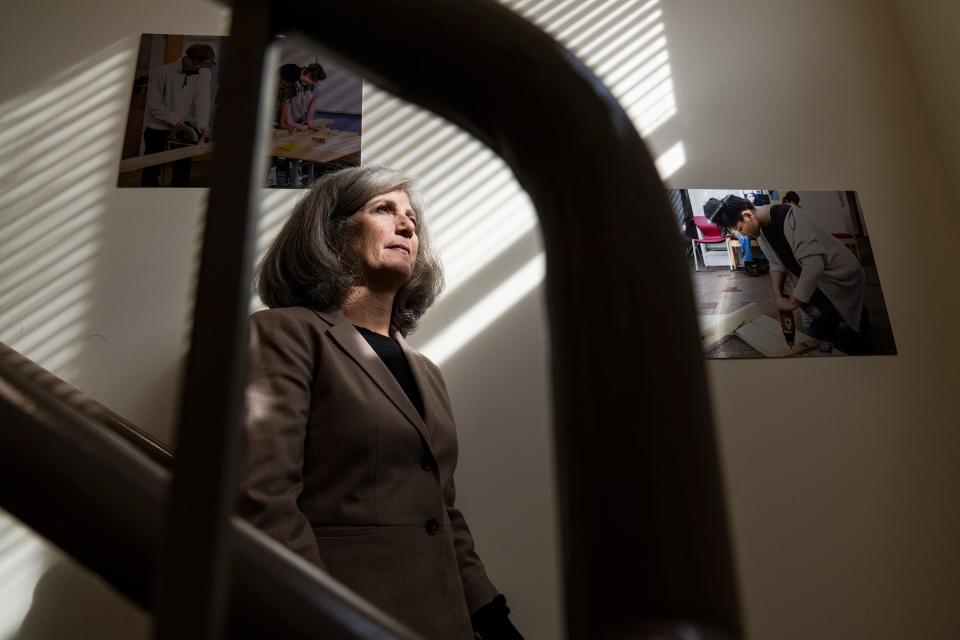

“It really takes a team approach,” said Mara Nicastro, head of Nora School, a small college preparatory school in Silver Spring, Maryland. “We work in conjunction with the family and the therapist ... and talk about what is it that can help make this transition smooth because the student is ready and knows it’s time to find a space to move forward.”

Before making that leap, Dalton said most school avoidant students undergo a combination of cognitive behavioral therapy and exposure therapy to understand what exactly the student is avoiding and gradually build their tolerance to that source of anxiety. This may look like staying in the car at the school parking lot or walking into the guidance counselor’s office and leaving.

Parents with anxiety have difficulty guiding their children in uncomfortable situations, Dalton said, as they reckon with their own traumas related to school. But it's important to seek help.

Schools need to work with parents and therapists to make the appropriate accommodations, Nicastro added.

“We recognize that our students are learning how to move through their discomfort, their anxiety, and give them opportunities to use those coping strategies.”

Looking forward: What’s being done to help students?

Experts say not all schools – especially large districts – have the resources to operate like the Nora School, which limits enrollment to 70 students.

Many schools don’t reach the American School Counselor Association recommended counselor-to-student ratio of 1 to 250. The average ratio across all schools is 1 to 464, according to the association, and nearly 3 million of those students don’t have access to other school support staff, like a school psychologist or social worker.

But experts say things are slowly changing. For example, the Biden administration announced Monday nearly $100 million will be awarded across 35 states to increase access to school-based mental health services through the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, which was signed into law June 2022.

Meanwhile, school systems and professional organizations are engaged in a national conversation about school avoidance and related protocols, said Duncan Young, CEO of Effective School Solutions, a mental health services provider for K-12 school districts.

Some protocols have been implemented and include a social-emotional curriculum, mental health counseling and personalized care for students whose mental health challenges impede their ability to operate in a traditional school setting.

“We’re seeing this transition right now,” Young said. Instead of viewing school avoidance as a behavioral problem, “school districts are building their mental health literacy and understanding the linkage between school avoidance and mental health.”

Meanwhile, some families question the rigid structure of a traditional school system.

Katie, a mother of three who lives in the St. Louis area in Illinois, said her high-school-age son was school-avoidant, but his mental health has significantly improved after transitioning full time to remote learning.

“He’s much healthier,” Katie said, who is on the school board and spoke on the condition that she not be fully identified. “He’s participating in schoolwork, he’s socializing, he’s attending family dinners again, his depression is so much better, anxiety is so much better.” He's also working and visiting colleges with plans to continue his education.

Experts urge families to seek professional help through a doctor, therapist or school counselor if anxiety becomes debilitating enough that it affects daily life, relationships and job, or if someone is having thoughts of hurting themselves or others. If you or someone you know may be struggling with suicidal thoughts, dial 988 to reach someone with Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. They're available 24 hours a day and provide services in multiple languages.

In the real world, most people can choose whom they work for or where they go to college, she noted. But students don't have that flexibility in a traditional school system.

"Children have not always been educated in this one little box," Katie said. "Whatever that looks like for (my son), I have all the faith in the world that he will be successful one day. I don’t question it for a second anymore."

Despite avoiding school for four years, Demsky's son graduated, secured a job and manages his anxiety independently, she said. She hopes her story comforts other parents and shows that children can have productive lives after school avoidance.

"I had that fear that my son was going to live in my basement for the rest of his life. ... That is the fear of every parent," Demsky said. Now, her son is "thriving."

"I'm really proud of him."

Follow Adrianna Rodriguez on Twitter: @AdriannaUSAT.

Health and patient safety coverage at USA TODAY is made possible in part by a grant from the Masimo Foundation for Ethics, Innovation and Competition in Healthcare. The Masimo Foundation does not provide editorial input.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: School avoidance becomes crisis after COVID