The row over Miss France’s pixie cut is ridiculous – short hair represents everything the French love

France is the nation that did more to make short hair on women fashionable than any other. True, the Brits had Twiggy, Cilla Black and Dusty Springfield. But most British women backcombed and overfussed their short hair so that it effectively became long hair, minus the obvious advantages.

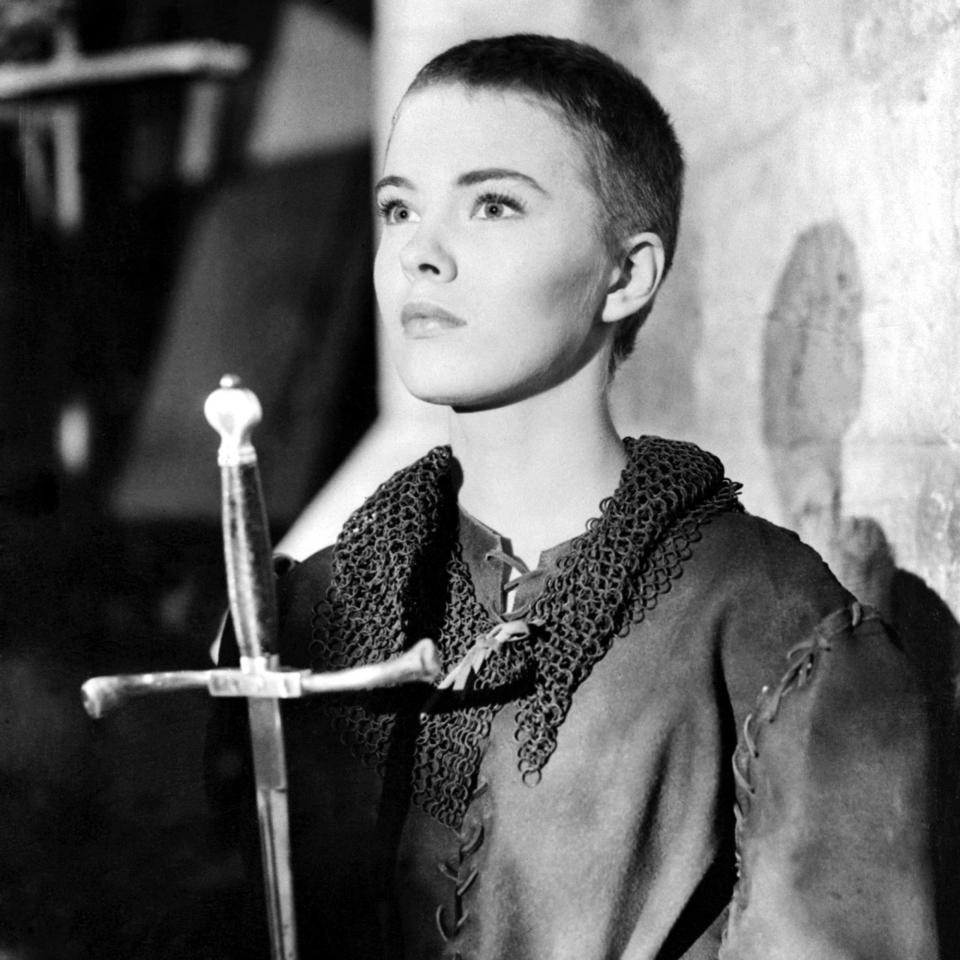

France had unapologetic short-haired heroines: Jeanne Moreau, Juliette Gréco, Coco Chanel, Jean Seberg (American but co-opted by French New Wave cinema) and, briefly, Brigitte Bardot. Seberg’s big breakthrough in Otto Preminger’s Saint Joan was conditional on her going for the big chop. She kept it and it served to make her one of the coolest, hippest, most modern-looking women of that, and subsequent, eras.

French intimacy with short hair stretches further back than New Wave, however, which is why the current hullabaloo about the new Miss France, Eve Gilles, having a pixie cut is so very strange. Josephine Baker, another American performer they adopted as their own, had the quintessential waved crop in the 1920s that arguably heralded the jazz age.

But never mind Josephine B. What about Josephine de B (Joséphine de Beauharnais, later Bonaparte) and her pixie cut, circa 1794? De Beauharnais’s shorn hair was less the bold choice of someone sitting in the salon of a renowned coiffeur and more the badge of someone who’d been imprisoned and was awaiting her summons to the guillotine. But during the Great Terror that followed the toppling of the Bourbon monarchy, short hair for women became, for a while, à la mode.

De Beauharnais would grow her hair back, but even when it was short, she never lacked romantic suitors – which is exactly what we’d expect in a nation of gamine-style appreciators. For a moment, short hair became fashionable among the elite, even among a few rebellious spirits in England (Lady Caroline Lamb, lover of bisexual poet Byron, for one). It didn’t last, not least because of a reactionary movement positing that short hair on women could lead to fevers and gum decay – although not in men. Funny that.

It figures that French revolutionaries (and the majority of modern French people consider themselves to have a revolutionary streak) like short hair on women. For thousands of years, it has symbolised everything they applaud (intellectually at least): freedom, equality and daring.

Alas, so much of what on the surface appears to be emancipated and spontaneous is just that – surface. The fact the French are still broadcasting beauty pageants on mainstream television – and drawing 7.5 million viewers for it – suggests that at heart they’re as staid and traditional as a soggy omelette.

And here we come to the nub of things. For the current Miss France brouhaha, short hair has become entangled with the culture wars. The “problem” with the short style worn by Gilles is that, according to some critics, it makes her look androgynous; and in the new world paradigm, androgyny is an affront to those attempting to hold back the effluence of “woke”.

Gilles seems to have fanned the flames by making her hair appear to be a political choice, rather than one that enhances her cheekbones. “We’re used to seeing beautiful Misses with long hair,” she said after being crowned, “but I chose an androgynous look with short hair,” adding that every “woman is different, we’re all unique”.

She’s right that going short remains a big deal, emotionally and socially, for many women, even in 2023 – as it has done throughout history. In Apple TV’s recent The Super Models documentary, Cindy Crawford recounted how she was tricked into having her hair lopped off on an early job with the photographer Patrick Demarchelier. It was the late 1980s and Crawford, a veteran of mid-western catalogue work, really wanted the gig but staunchly insisted she would keep her hair. The bookers agreed, but once she was on the shoot and her hair had been swept back in a ponytail, she heard the unmistakable swish of slicing scissors. The way Crawford recounted the story 30 years later was an emotive reminder of just how much power resides not just in a man’s (Samson) hair, but in a woman’s too.

It’s not just that, biologically, hair has always been a key sexual signifier, it also represents health, youth and money. Historically, the rich could amplify nature’s shortfall with wigs – generally made from hair supplied, in abundance, by the poor. In 1840, the writer Thomas Adolphus Trollope observed the stream of women at a fair in Brittany, France, queuing up to sell their hair to the shearers there – a source of income highlighted in Victor Hugo’s 1862 Les Misérables. The heroine Fantine sells her hair (and then her teeth) to feed her child.

No wonder that on a basic, atavistic level, short hair on women came to be seen as less and less desirable. Yet at the same time, civilised women of all classes and religions have been expected to tame their luxuriant tresses beneath wimples, bonnets and veils, lest they lead men astray. For the truly errant – Victorian female prisoners and, later, in the 20th century, female French collaborators – having their hair forcibly shaved was a very present threat.

Women’s hair, whatever its length, style and condition, has always been contentious and commodified. If it’s not impecunious women selling theirs (as still happens now, to provide the flourishing trade in hair extensions), it’s more affluent women getting their hair chopped to create a lucrative career statement: Victoria Beckham, Demi Moore, Sharon Stone and Linda Evangelista.

Clearly challenging society’s follicular expectations can be worked to advantage. Evangelista has said that after French hairdresser Julien d’Ys cut her hair in a gamine Eton crop in 1988 her day rate tripled. And for all the fuss in France, Gilles, who represented the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region, won the Miss France contest.

And that’s where fashion steps in. Every decade finds its short cut of choice, which in turn comes to express a line of argument against whatever long style has been popular. The 1950s came up with the pixie as the antidote to everything that was oppressive in the previous era. The 1960s had Vidal Sassoon’s five-point geometry as a neat, architectural counterpoint to tortured beehives. The 1970s went big on glam rock’s feather cuts as the quintessential rebuttal to long hippy hair. The 1980s fell in love with neat, 1930s-style Eton crops, as worn by Rupert Everett in Another Country – a reaction to the extravagant gelled spikes of punk. And then in the 1990s came Gwyneth Paltrow’s Sliding Doors side-parted mop.

After almost two decades of almost waist-length ubiquity, short hair is quietly coming back on catwalks and red carpets. As someone who took the plunge a year ago – against the advice of her husband – I sadly cannot report a tripling of my salary. But I can say that when you find a short cut that suits you, you will never receive so many compliments. Liberate yourself from the tyranny of hair extensions and a zillion other questionable hair boosters and treatments – the true meaning of doing something for yourself and not to please others – and eventually the naysayers (husbands included) will love it.