Rosalynn Carter, former first lady who pushed for mental health reform, dies at 96

Rosalynn Carter, the formidable first lady who helped modernize and expand the role of a U.S. president’s wife as she sat in on White House Cabinet meetings, spoke freely and pushed for mental health reform, has died.

Carter, who with her husband, Jimmy, remained steadfastly committed to public service after returning to private life, died peacefully at home Sunday in Plains, Ga., with family by her side, the Carter Center said in a statement. The nation's oldest living first lady was 96.

The center announced that she was suffering from dementia in May, three months after the former president entered hospice care at home. On Saturday, the center announced that Rosalynn also was in hospice care.

The couple's last public appearance together was in September, when they rode through their beloved hometown during the annual Plains Peanut Festival.

“Rosalynn was my equal partner in everything I ever accomplished," former President Carter said in a statement on Sunday. "She gave me wise guidance and encouragement when I needed it. As long as Rosalynn was in the world, I always knew somebody loved and supported me.”

Tributes to the former first lady and condolences to the Carter family poured in Sunday. President Biden and First Lady Jill Biden said Carter "walked her own path, inspiring a nation and the world along the way. ... The deep love shared between Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter is the definition of partnership, and their humble leadership is the definition of patriotism."

Throughout his time in office, President Carter quoted his wife frequently in discussions with advisors and bombarded her with memos on which he scribbled, “Ros, what think?” according to the 1988 book “Presidential Wives.”

“I can’t tell you how important she was,” the late Hamilton Jordan, President Carter’s former chief of staff, told People magazine in 2008. “People who really know the Carters say you never knew quite where Rosalynn stopped and Jimmy began.”

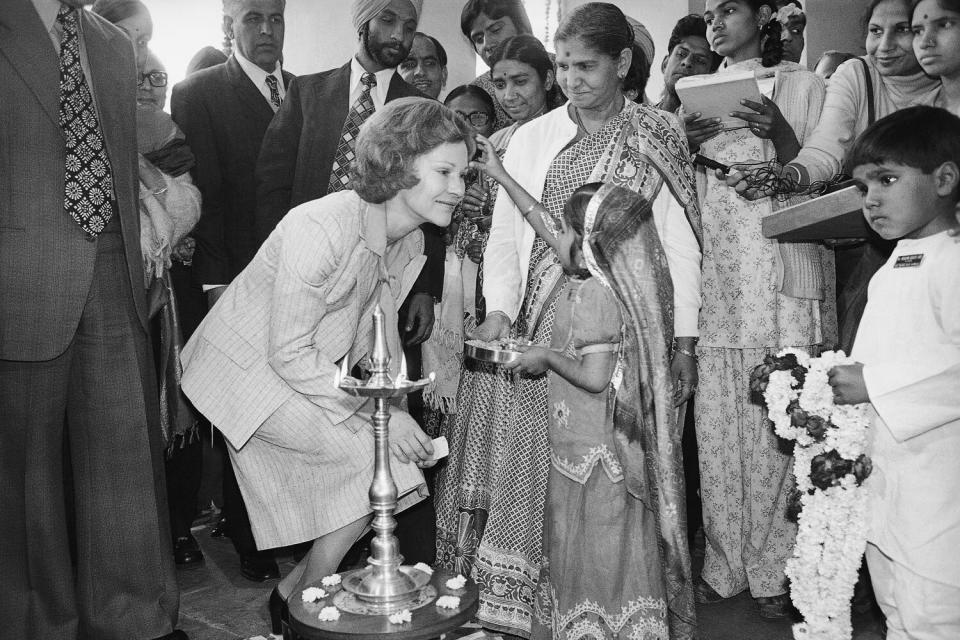

Within a few months of becoming the 39th president in 1977, Jimmy Carter sent his wife on a mission to Central and South America to promote human rights and democracy. Because she was not an elected official, the media sharply criticized the trip.

When an American reporter in Ecuador asked if her diplomacy was “an appropriate exercise” of her position, she replied: “I am the person closest to the president of the United States, and if I can explain his policies and let the people know of his great interest and friendship, I intend to do so.”

Such direct responses caused reporters to nickname the soft-spoken and tenacious Georgia-born first lady “the Steel Magnolia.” She didn’t mind.

Read more: Former First Lady Rosalynn Carter has dementia, the Carter Center says

“I am strong. I do have definite ideas and opinions. In the sense that ‘tough’ means I can take a lot, stand up to a lot, it’s a fair description,” she told Good Housekeeping magazine in 1976.

Bitterly disappointed when her husband lost the 1980 presidential election to Ronald Reagan, Carter thought “we’d go home and we’d be bored to death the rest of our lives,” she told The Times in 1998. Then she laughed. “But we haven’t had time.”

They settled back into their modest ranch-style home in Plains and reinvented themselves as roving ambassadors who traveled the world, determined to help others one project at a time.

Through the Atlanta-based Carter Center — a nonprofit think tank the two founded in 1982 — the couple had “an almost unlimited menu” of opportunities, the former president told The Times in 1999.

Read more: The Carters: What you know may be wrong (or not quite right)

They often went to Africa, where the center sponsored healthcare and agricultural projects in dozens of countries. They were the marquee hands-on volunteers for Habitat for Humanity, a network of volunteers that builds homes for people in need. She continued to work to raise awareness of mental health issues and in 1991 co-founded the immunization program Every Child By Two.

“We seem to have an awful lot of things going on,” the former president told People in 2000. “But basically we work for peace and health.”

In 1999, upon awarding the Carters the Presidential Medal of Freedom — the nation’s highest civilian honor — then-President Clinton said the couple had “done more good things for more people than any other couple on the face of the Earth.”

The Carters largely earned their living writing books — his, hers and, only once, theirs. Their collaboration on the appropriately named “Everything to Gain: Making the Most of the Rest of Your Life,” published in 1987, had been stormy.

“We can’t do that” again, Jimmy Carter told The Times in 1999. “Rosalynn is too strong-willed. And I am too.”

Read more: Jimmy Carter turns 99 at home with Rosalynn and other family as global tributes arrive

Widely considered one of the most activist first ladies since Eleanor Roosevelt, Rosalynn Carter arrived in the White House with her own platform — mental health reform. It was a cause she took up while helping her husband get elected governor of Georgia in 1970.

She was a pioneer in destigmatizing mental illness, said Douglas Brinkley, author of the 1998 book “The Unfinished Presidency.”

“By speaking openly, she helped millions cope with their depression and anxiety,” Brinkley said in a 2000 interview.

As first lady, Carter became a leading advocate for mental health reform and guided legislative reform on behalf of the nation’s mentally ill.

Her work resulted in passage of the Mental Health Systems Act of 1980, which advocated health insurance coverage for people with mental illness and for their protection against discrimination. Although most of the act’s funding was cut by the Reagan administration, “it still has an impact,” she told The Times in 1998.

Read more: Rosalynn Carter, 96-year-old former first lady, is in hospice care at home, Carter Center says

Born Aug. 18, 1927, in Plains, Eleanor Rosalynn Smith always went by her second name. She was the eldest of four children of Edgar Smith and his wife, the former Frances “Allie” Murray.

Rosalynn’s childhood ended, she later wrote, with the death of her father from leukemia when she was 13. Decades later, she would write “Helping Yourself Help Others,” a guide for caregivers that grew out of her own experience caring for her ailing father.

To make ends meet, her mother took in sewing and eventually worked in the Plains post office. Rosalynn helped run the household and still managed to be valedictorian of her 1944 high school class.

Read more: In his final days, Jimmy Carter on cusp of a humanitarian goal: Eradicating a parasitic worm

Although both Carters were from Plains, he was three years older so “they didn’t really know each other,” she later said, and grew up attending different churches. As an adult, she converted to his Baptist faith.

While a sophomore at Georgia Southwestern, then a junior college in nearby Americus, she was captivated by a photograph of Jimmy Carter in his U.S. Naval Academy uniform that was displayed by his sister Ruth, who was Rosalynn’s best friend.

He seemed “glamorous and out of reach,” she later wrote, but Ruth arranged for them to work together on a Carter family project in June 1945, and he took Rosalynn to the movies that same night.

“She’s the girl I want to marry,” he told his mother after their first date, according to an oft-repeated story.

On July 7, 1946, they were married after his graduation from the Naval Academy. Soon after, they reported to his first duty station, Norfolk, Va., and had their first child the following July.

“I was away for the first time and had a baby,” she later recalled. “Jimmy was gone much of the time, and I had to take care of everything. It taught me that I could do what I had to do.”

She soon thought of Navy life as exciting as they moved around the country, living in Connecticut, Hawaii, San Diego and New York and having three sons between 1947 and 1952. Their daughter, Amy, would be born in 1967.

When his father died of cancer in 1953, Jimmy Carter decided to abandon his Navy career and return to Plains to take over his family’s peanut business, which was in disarray. Rosalynn was nearly inconsolable.

“I argued. I cried. I even screamed at him,” she recalled years later. “I loved our life in the Navy. I didn’t want to live in Plains. I had left there, moved on. I thought the best part of my life had ended.”

Things in Plains were dire. It was 1954, and a drought had devastated the peanut, corn and cotton crops. The Carters made less than $200 that year, the equivalent of just over $2,200 today.

The next year, as the business was turning around, Jimmy asked Rosalynn if she would help in the office. After taking a correspondence course in bookkeeping and accounting, she took over the books for the family enterprise. By the time Jimmy began his campaign for the White House, revenue from their enterprises had grown to more than $2 million a year.

“I loved it,” Rosalynn later recalled of yet another new experience. “To make all those books balance? I loved it better than anything I had ever done.”

They grew together as full partners, and when he successfully ran for the state Senate in 1962, she helped him campaign — and kept the business running back home.

Once again, she enjoyed a new role: political wife. When Jimmy lost his first race for governor — to segregationist Lester Maddox — she was there to help him strategize, and successfully rebound when he ran again in 1970. Though a political unknown outside Georgia, Jimmy Carter set his sights on Washington just four years later when he announced he was running for president.

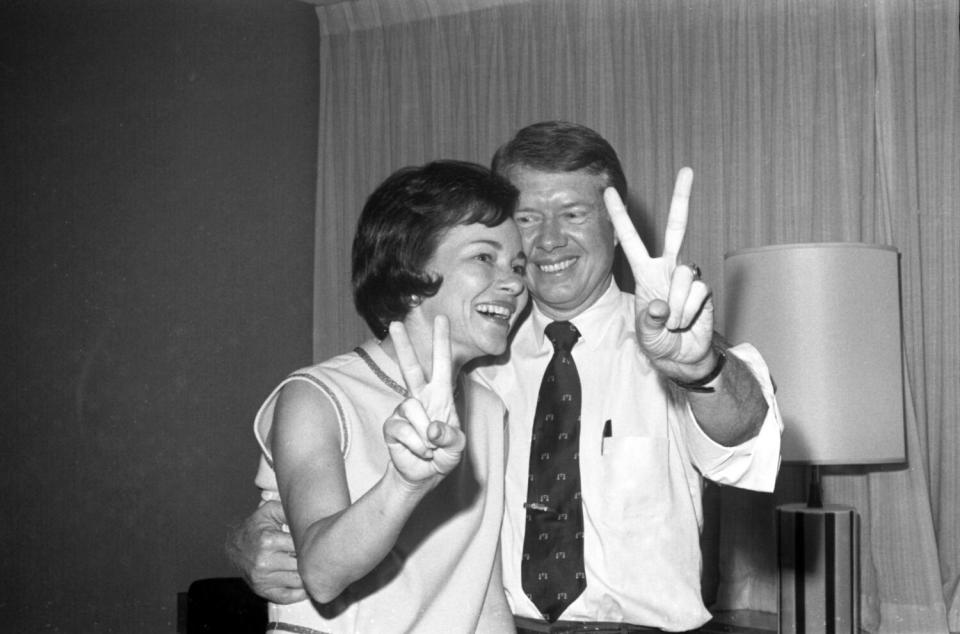

The Carters often campaigned separately to get his name out before the public, and Rosalynn frequently put in 18-hour days. When he beat President Ford in the general election, she was given major credit for the victory.

On Inauguration Day — Jan. 20, 1977 — the Carters set a populist tone for the next four years, walking hand in hand from the Capitol to the White House with their family. She treasured it as the greatest day of her life.

Rosalynn wore the same blue chiffon gown to the inaugural balls that she had worn six years earlier to Jimmy’s gubernatorial ball, in keeping with her husband’s decision to host a no-frills People’s Inaugural, complete with $25 ball tickets.

From the start, his presidency was a partnership with his wife. The first couple had a standing date each Wednesday for lunch at the White House, when she would tell him what people were thinking and feeling. Both worked for passage of the Equal Rights Amendment, and she said its failure was the greatest disappointment of her White House years.

On the home front, she surrounded herself with family. Two sons who worked or studied in Washington lived in the White House with their wives. Amy, who was 9 when the family moved in, got a treehouse on the South Lawn.

In writing her 1984 autobiography “First Lady From Plains,” Rosalynn relied heavily on a diary she began keeping after meeting President Nixon in 1972 at the White House.

“He just walked over and said: ‘Young lady, do you keep a diary?’ I said: ‘No, sir,' and he told me: ‘You’d better keep one or you’ll be sorry. These are exciting times.’”

By 1980, President Carter’s failure to gain freedom for the 52 Americans held hostage for more than 14 months at the U.S. embassy in Tehran was casting a long shadow on his presidency. While he stayed close to the White House, trying to negotiate the hostages’ release, Rosalynn once again took to the campaign trail.

By election day, the Carters knew the race was a lost cause. The hostages were freed the day of Reagan’s inauguration.

Later, the Democratic Party asked her to run for the U.S. Senate from Georgia but she declined, saying she wouldn’t want to live apart from her husband.

The two did “everything together,” which was the secret to their close bond and vitality, the former president told The Times in 1999. “We take up new habits, like climbing mountains or bird watching or fly fishing or downhill skiing.”

Yet several years after leaving the White House, she told an interviewer, “I won’t say it’s a relief not to be first lady, because I enjoyed every minute of it.”

She is survived by her children, Jack, Chip, Jeff and Amy; 11 grandchildren; and 14 great-grandchildren, according to the center. A grandson died in 2015.

Beyette and Nelson are former Times staff writers. Staff writer Jenny Jarvie contributed to this report.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.