These roles are growing like never before in Delaware schools. And they aren’t the teachers

Clarification: This story originally mentioned the starting salary for a para at the state portion alone, and it has since been updated to clarify paras also have additional salary paid by their district or charter.

Her eyes scan devices, following boards of nonverbal cues.

It’s how Jennifer Hickman’s students communicate with her. The instructional para plans for her day every morning, but she has to pivot with each feeding plan, each bathroom break, any individualized instruction, any crisis in elementary special education.

It doesn’t stop. After all, she’s leading the classroom now. She should be assisting a teacher, perhaps alongside three other paraprofessionals in Capital School District.

“My brain is on,” said the para running her room for nearly three years. “What does this student need? From this student, to that student, to this student.”

Without formal training for the role she’s filling, Hickman just hopes she and one other staff member are doing right by every student. Her high-needs learners can’t tell her in so many words.

And this story isn’t unique.

Some paraprofessionals said they don’t think the public knows much about their roles. Most have associate degrees; many work second jobs to make a livable wage. And looking back, many of these support positions have expanded across Delaware schools like never before.

Now, meet four working in Delaware. They’re working alongside overworked teachers and strained resources. They’re leading group instruction or one-to-one support for students in special education. Or, in some cases, they’re covering classrooms on their own while an educator shortage persists.

Unions throughout state districts have pushed for increased rates for paras working as teachers, some making it official just as recently as this school year. Starting state salary portion for a para is about $23,800 now, with a combined 3% bump eyed for next fiscal year. That joins additional local compensation that varies by district and charter. The over 3,000 roles have been folded into ongoing conversations on pay increases across education support personnel, within the state’s Public Education Compensation Committee work and drafted state budget.

"I think the increased focus on paraprofessionals stems from a number of things happening at the same time in education," said Lauren Bailes, program coordinator for University of Delaware's doctoral program in educational leadership. "There is certainly a recognition that we are in a crisis of teacher retention and recruitment, and paraprofessionals often have a record of service and experience that already benefit schools in many ways."

Attention has also sharpened on diversifying the teacher workforce. More than 40% of Delaware's paraprofessionals are people of color, the associate professor noted, which is nearly double the proportion among its teachers.

From career paras to those working to step into teaching, hope remains for greater support.

“Some days, I am nervous about what the future of education will look like — because if you look around, you see people who are burnt-out and tired and overworked, and sometimes, feelings of hopelessness creep in,” said fellow para Tameka Mays, from a Colonial school.

“But I'm always hopeful that we will find a way to continue to give people opportunities.”

'Remove the barriers, give them as much support as they need'

Students yelped in excitement.

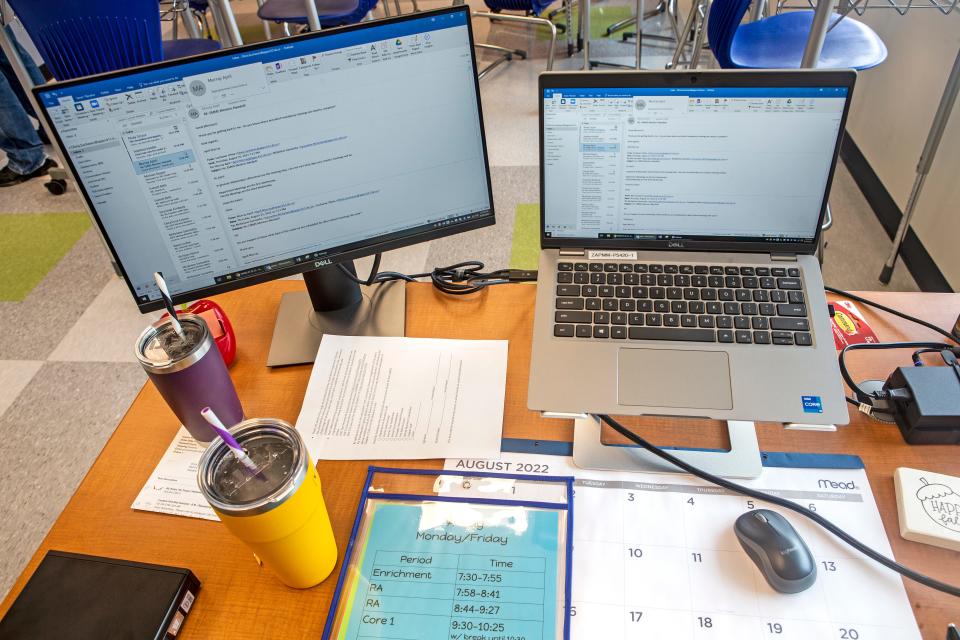

Tameka Mays asked her middle schoolers to introduce themselves one by one, down a small semicircle of desks, interrupting their typical morning routine. The classroom para working in special education and vocational training still managed to bring calmness back to the room.

In her George Read Middle School, paras like Mays work alongside teachers, one-on-one with students navigating school with disabilities, as well as cover classrooms. On this February morning, Jeneen Barbour’s voice filled the room. The fellow para agreed to cover that Tuesday for the first time, already on track to becoming a certified teacher.

Mays keeps seeing more paras step up to fill gaps. The now-vice president of Delaware State Education Association watched as roles evolved from mostly toileting and mobility support, to paras working with students in regular classrooms, small group reading support and more. People are starting to notice.

“I just don't believe that our stories, and the work that we’ve done, were always highlighted in the way that it’s been highlighted post-pandemic,” said the para of nearly 20 years, having returned to the classroom in 2022. “Considering some of the burden of continuing to help the school run is on the shoulders of education support personnel — either filling in for teacher shortages in classrooms, or going into that para-to-teacher track.”

Lawmakers have been watching this, too. Last year, legislation pushed to smooth the pipeline for paras to become full teachers, if they aim for it, specifically allowing them to come in with higher salaries based on their classroom experience.

Before that legislation, as primary sponsor and Senate Majority Whip Elizabeth “Tizzy” Lockman explained last session, "that transition would likely result in a pay cut for our most experienced paras."

Mays says students need certified instruction. She believes the state could do more to remove affordability barriers, strengthening the pipeline for support personnel to get more training.

“I think that's where we start,” Mays said, referencing para support and Grow Your Own models. “We grab the people who are interested in the career first, and we remove the barriers and give them as much support as they need, as they try to become certified teachers.”

It’s not a simple equation, though.

Next read: 'We cannot normalize failure': Wilmington Learning Collaborative eyes lofty goals ahead

'A lot of pressure'

At first, she was just asked to fill in.

Jennifer Hickman’s Kent County Community School — serving over 200 students from ages 3 to 21 living with physical, cognitive, communication and other varying degrees of ability — needed to find a new teacher for her elementary class. The instructional para of about five years would just need to lead the room in summer 2022, until a replacement was hired.

“That never happened,” said the Dover educator. And she hasn’t looked back.

She estimates her building could use 20 more sets of hands, while six other paras already fill in as teachers like her. Each day feels like a game of balancing resources. Hickman knows why most of the paras stick with it, and it isn’t just the extra $100 a day her union achieved by this school year.

“It's knowing and meeting the needs of my students each and every day,” she said. “And I think them not having a voice impacts me even harder. Like, I am their voice. I am the one who's going to stand up for them because they can't go home and say, ‘Hey, you know, school was lacking today.’”

But pressure mounts.

“We're just not really given the tools and resources to really succeed in being a teacher,” she said. “I don't have a background, so I was never trained, except for by some veteran teachers.”

Hickman now studies at Wilmington University. She’s often running behind on assignments, struggling to find the mental space for more work after the school day. She got state help to cover the cost of education — but that isn’t the only thing holding her back.

She switched her major from education to behavioral science, as “the burnout is real” amid a lack of support. Hickman plans to bring skills back to school, but she doesn’t know what shape that will take.

For now, she’s still focused on her students.

“It's a lot of pressure,” she said. “But my students are the greatest prize. When they can independently say ‘I need to go to the bathroom,’ or they can independently walk to the bus, and they can use their device to say ‘No, stop,’ and have autonomy over their own body — that's the reward.”

Education: St. Elizabeth Catholic School community calling for answers as president is cut

'Without us, this wheel isn't moving'

Jossette Threatts knew the conversation needed to change post-pandemic.

COVID-19 crisis sharpened a trend she was already watching as president of the Caesar Rodney Education Association for over a decade.

“Here we are. We're not just making copies for you anymore,” said the career paraprofessional at Major George S. Welch Elementary. “We are in the classrooms. We are working with students. We are engaging them. We are working with them on all the subjects that they have the inside of the building at all grade levels.”

When last school year began, from special education support to the general population, her paras filled holes as the district battled empty positions. Threatts fought for her district's compensation to show it. Caesar Rodney agreed to up pay $75 a day for paras working as teachers, she said, if they’re working that role for two weeks or more.

“The teacher shortage is not getting any better,” she said. “And they need us to do the work, to pick up the slack, to make sure that the kids are getting what they need in the classroom.”

Another union leader echoed her from some 40 miles north.

“The room simply cannot function without the paraprofessionals,” said Gretchen Loose, a fellow para at Brennen School. “Each child has their own separate IEP, their own behavior support plans, having six to ten individuals in a special-needs classroom: You can't throw one teacher at it.”

Loose, president of the Christina Paraprofessional Association, leads the largest group of paras in Delaware. Navigating behavior challenges, learning loss, mental health issues, strained staffing — she says the paraprofessional role has become crucial.

“That has always been a challenge with any special-needs population,” she continued. “But a little before the pandemic, and certainly post-pandemic, the roles of professionals in general education classrooms has increased exponentially.”

Loose said her district is down about 80 teachers across its 19 schools. Those classrooms either had to be dissolved and pushed into other classes, or paras stepped into the roles.

“With the teacher shortages, paraprofessionals are filling the roles of vacant teachers or are acting as long-term substitutes for those positions,” said the para of 25 years. “So, they're being asked to step up and basically run the classrooms with additional professional support from building administrators.”

It’s a daunting task. Loose said most Delaware school districts are compensating paraprofessionals for the increased workload, while pointing toward Grow Your Own programs to encourage further education. Loose said these programs should be strengthened, as with current average salaries, because higher education costs remain a barrier.

Whether teachers, counselors, principals or administrators — it’s a tough time to be in education in any capacity, Loose said. But Delaware cannot forget about the grease in the machine.

“I am invigorated each day to come to work because of what I see all of my colleagues doing in their classrooms and buildings across the district,” she said. “I’m like: ‘Guys, we are the grease that makes the wheel move right. Without us, this wheel isn't moving.’”

Higher education: Another Ivy brings back SAT, ACT scores. Will University of Delaware stay test-optional?

Got a story? Kelly Powers covers race, culture and equity for Delaware Online/The News Journal and USA TODAY Network Northeast, with a focus on education. Contact her at [email protected] or (231) 622-2191, and follow her on Twitter @kpowers01.

This article originally appeared on Delaware News Journal: Paraprofessional roles have grown like never before in Delaware schools