'A reckoning is near': America has a vast overseas military empire. Does it still need it?

MANAMA, Bahrain – After weeks at sea, hundreds of young Americans shed their military uniforms for baseball caps and T-shirts and poured forth from the main gates of the heavily fortified U.S. Navy's Fifth Fleet base, a major hub for U.S. naval forces in the Middle East.

The aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln had just docked in Bahrain, a small Arab island nation on the southwestern coast of the Persian Gulf. The disembarking U.S. service members were intent on cutting loose for a respite from their national security mission patrolling one of the world's busiest and most volatile shipping lanes.

About 200 miles to the east, across a body of water that has seen many tense naval encounters and acts of sabotage, sat America's longtime adversary Iran.

It was November 2019.

A few months later, the U.S. and Iran would nearly enter into an open confrontation after Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps fired ballistic missiles at two Iraqi military bases housing U.S. soldiers. The attack was retaliation for the Pentagon's assassination of senior Iranian commander Qasem Soleimani.

For the sailors, Bahrain's "American Alley" was a taste of home: a thoroughfare of fast-food restaurants and shops catering to Westerners. The sailors clutched iPhones and Starbucks coffee and fended off attempts by locals to sell them watches and other trinkets.

For America's military planners back in Washington, the sailors represented a longstanding bedrock of U.S. national security: one of the Pentagon's hundreds of footholds all over the planet.

Sea change in security threats

For decades, the U.S. has enjoyed global military dominance, an achievement that has underpinned its influence, national security and efforts at promoting democracy.

The Department of Defense spends more than $700 billion a year on weaponry and combat preparedness – more than the next 10 countries combined, according to economic think tank the Peter G. Peterson Foundation.

INTERACTIVE: 3 maps show why the U.S. is the 'world's police'

The U.S. military's reach is vast and empire-like.

In Germany, about 45,000 Americans go to work each day around the Kaiserslautern Military Community, a network of U.S. Army and Air Force bases that accommodates schools, housing complexes, dental clinics, hospitals, community centers, sports clubs, food courts, military police and retail stores. About 60,000 American military and civilian personnel are stationed in Japan; another 30,000 in South Korea. More than 6,000 U.S. military personnel are spread across Africa, according to the Department of Defense.

Yet today, amid a sea change in security threats, America's military might overseas may be less relevant than it once was, say some security analysts, defense officials and former and active U.S. military service members.

The most urgent threats to the U.S., they say, are increasingly nonmilitary in nature. Among them: cyberattacks; disinformation; China's economic dominance; climate change; and disease outbreaks such as COVID-19, which ravaged the U.S. economy like no event since the Great Depression.

Trita Parsi, co-founder of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, a Washington-based think tank that advocates for U.S. military restraint overseas, said maintaining a large fighting force thousands of miles from U.S. shores is expensive, unwieldy and anachronistic.

"It was designed for a world that still faced another military hegemon," Parsi said. "Now, pandemics, climate chaos, artificial intelligence and 5G are far more important for American national security than having 15 bases in the Indian Ocean."

It may also be counterproductive. Parsi said terrorism recruitment in the Middle East has correlated with U.S. base presence, for example.

Meanwhile, American white supremacists, not foreign terrorists, present the gravest terrorism threat to the U.S., according to a report from the Department of Homeland Security issued in October – three months before a violent mob stormed the Capitol.

Delivering his first major foreign policy speech as commander-in-chief, President Joe Biden said earlier this month that he instructed Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin to lead a "Global Posture Review of our forces so that our military footprint is appropriately aligned with our foreign policy and national security priorities."

BIDEN: New twist on Trump's 'America First' foreign posturing

How big is the US military investment?

At the end of World War II, the U.S. had fewer than 80 overseas military bases, the majority of them in the allies' vanquished foes Germany and Japan.

Today there are up to 800, according to data from the Pentagon and an outside expert, David Vine, an anthropology professor at American University in Washington. About 220,000 U.S. military and civilian personnel serve in more than 150 countries, the Defense Department says.

China, by contrast, the world's second-largest economy and by all accounts the United States' biggest competitor, has just a single official overseas military base, in Djibouti, on the Horn of Africa. (Camp Lemonnier, the largest U.S. base in Africa, is just miles away.) Britain, France and Russia have up to 60 overseas bases combined, according to Vine. At sea, the U.S. has 11 aircraft carriers. China has two. Russia has one.

The exact number of American bases is difficult to determine due to secrecy, bureaucracy and mixed definitions. The 800 bases figure is inflated, some argue, by the Pentagon's treatment of multiple base sites near one another as separate installations. USA TODAY has determined the dates for when more than 350 of these bases opened. It's not clear how many of the rest are actively used.

"They're counting every little patch, every antenna on the top of a mountain with an 8-foot fence around it," said Philip M. Breedlove, a retired four-star general in the U.S. Air Force who also served as NATO's Supreme Allied Commander for Europe. Breedlove estimated there are a few dozen "major" U.S. overseas bases indispensable to U.S. national security.

Yet there's no question that the U.S. investment in defense and its international military footprint has been expanding for decades.

When the Korean War came to an end in 1953, eight years before President Dwight D. Eisenhower warned in his farewell address of a growing military-industrial complex, the Pentagon was spending about 11% of GDP, or $300 billion, on the military, according to the Defense Department and a manual calculation by USA TODAY. Today the Pentagon easily allocates more than twice as much on defense spending each year, adjusted for inflation, even if the overall budgetary figure represents a far lower percentage of U.S. GDP at just 3%.

COVID-19 kills and costs more

Even as the U.S. spends more on defense, some experts say the U.S. military has been operating under a national security strategy that is remarkably unchanged since World War II and thus is ill-suited to newer, more dynamic threats.

"A lot of our military presence around the world is now really just out of habit," said Benjamin H. Friedman, policy director of Defense Priorities, a Washington think tank that advocates for a smaller world role for the U.S. military. "If at one point there was a strategic justification for it, often it no longer has it."

Retired U.S. Army Lt. Gen. David Barno and political scientist Nora Bensahel recently suggested the Defense Department should prepare for smaller budgets as money is shifted to other priorities.

"The pandemic has suddenly and vividly demonstrated that a large, forward deployed military cannot effectively protect Americans from non-traditional threats to their personal security and the American way of life," they wrote on the foreign policy website War on the Rocks. "In a deeply interconnected world, geography matters far less, and the security afforded by America's far-flung military forces has been entirely irrelevant in this disastrous crisis."

One stark illustration of how U.S. national security priorities may be out of sync with the times: Since 9/11, wars and various American anti-terrorism raids and military activity around the world have taken the lives of more than 7,000 U.S. troops and cost the federal government $6.4 trillion, according to Brown University’s Costs of War project.

As bad as that is, in less than 5% of that time, the coronavirus pandemic has accounted for more than 70 times the human toll as the U.S. exceeds 500,000 dead – also with at least a $6 trillion price tag, according to an analysis of Congress and Federal Reserve allocations. (The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has estimated that the pandemic has cost the U.S. at least $8 trillion.)

But preventing such deaths may not simply be a matter of taking money away from the Pentagon but shifting focus within it.

For instance, White House senior COVID-19 adviser Andy Slavitt announced Feb. 5 that more than 1,000 active-duty troops would begin supporting vaccination sites around the U.S.

Tom Spoehr, a retired Army lieutenant general and defense expert at The Heritage Foundation, a conservative Washington think tank, notes that the U.S. military has helped with international disease outbreaks in the past.

After an Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2014, the Pentagon sent troops, supplies and contractors to help stem a disease that killed more than 11,000 people and cost the economies of Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia an estimated $53 billion.

"We don't have the luxury of just saying, 'OK, the military wasn't that useful last year so we're going to turn it in and get an army of doctors instead," Spoehr said.

Spoehr said it's important the U.S. takes a wide view of national security that encompasses conflict and terrorism as well as pandemics, climate change and cybersecurity and overseas bases and troops have a role to play.

Climate chaos leading to social chaos

In 2017, the Trump administration dropped the Obama administration's designation of climate change as a national security threat. The omission came even though many members of Congress, U.N. Security Council principals, U.S. allies and dozens of security think tanks and research institutes say climate poses a potentially "catastrophic" threat to national and global security. (In one of his first executive orders, Biden re-elevated climate change as a national security priority.)

The World Health Organization estimates that climate change – ranging from insidious heat to flooding – already contributes to about 150,000 global deaths each year. Mark Carney, United Nations envoy for climate action and finance, has warned that the world is heading for death rates equivalent to the COVID-19 pandemic every year by the middle of this century unless drastic action is taken.

Along with wildfires, hurricanes and droughts, these natural disasters destabilize countries, including the U.S., by causing disease, food shortages, social and political instability and mass migration.

After the uncharacteristic winter storm paralyzed Texas, White House homeland security adviser Liz Sherwood-Randall issued a warning.

“Climate change is real and it’s happening now, and we’re not adequately prepared for it,” she said. “The infrastructure is not built to withstand these extreme conditions.”

The U.S. military, too, is not immune to climate consequences.

The Union of Concerned Scientists, a science advocacy group based in Boston, reported that the Pentagon is on the front lines of rising sea levels as climate-driven trends "complicate operations at certain coastal installations," including 128 bases in the U.S. valued at about $100 billion.

Still, Brad Bowman, a former U.S. Army officer and West Point professor, noted that the U.S. military is not a "Swiss Army knife" that can address every single threat. "It's a bit of a 'straw man'" argument to criticize it for threats it was not designed to meet, said the former national security adviser to members of the Senate Armed Services and Foreign Relations committees.

"Just because the American military can't solve every problem, that doesn't mean that it isn't useful for some problems," he said.

Former Defense Secretary Robert Gates said that while challenges such as climate change and pandemics "have arisen, the other ones have not abated." He said Russia is working on "highly sophisticated weapons and has completely reformed its military and for the first time since the end of the Cold War is operating submarines off of our East Coast. Iran is developing highly precise missiles. North Korea's (nuclear) programs are ongoing. The Chinese are continuing their military buildup."

China and cyberattacks: How the US compares regarding its greatest foes

On the whole, China's overseas military posture is relatively small.

China's official defense budget for 2020 was $178 billion, and Beijing has shown far less interest in matching the Pentagon's military arsenal and more concern about moving from an imitator to an innovator in biotechnologies, finance, advanced computing, robotics, artificial intelligence, aerospace, cybersecurity and other high-tech areas.

China, along with India, is now the world’s No. 1 producer of undergraduates with science and engineering degrees, accounting for about a quarter of such degrees globally, according to a U.N. report in 2018. The U.S. accounted for 6% of the total.

In a further sign of how China views future battlefields, Beijing is attempting to resurrect and expand the Silk Road, the ancient trade route that once ran between China and the West. China's Belt and Road Initiative is a multitrillion-dollar undertaking that involves helping build – often through loans – thousands of highways, railways, ports and industrial corridors across more than 60 nations. The project is aimed at forging an unrivaled economic security umbrella for China all over the world.

"China's playing a totally different game to the U.S.," said William Hartung, director of the Arms and Security Project at the Center for International Policy in Washington, D.C. "The U.S. is relying on traditional military bases, global military reach and training local militaries, while China is forging ahead by cutting economic deals that appear to be buying them more influence than the U.S.'s military approach."

Beijing also is building militarized outposts on disputed islands in the South China Sea, and the Pentagon believes it is adding overseas bases in Pakistan and possibly the western Pacific. China has recently expanded an Arctic research program that former U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said is a "Trojan horse" for its military.

To match the Chinese, Army Gen. Mark Milley, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said the U.S. needs to expand its naval fleet – including investments in robotic surface and underwater vessels. He said the U.S. needs to master new technologies from artificial intelligence to wearable electronics.

Biden, for his part, has promised to make cybersecurity a priority for his White House after one of the most massive cyberattacks ever was revealed in December.

For months, Russian government hackers known by the nicknames APT29 or Cozy Bear were able to breach the Treasury and Commerce departments, along with other U.S. government agencies. The same Russian group hacked the State Department and White House email servers during the Obama administration. The December hackers targeted an IT company used by all five branches of the U.S. military.

A bipartisan Senate investigation also found that Russia engaged in a sophisticated campaign to sow division ahead of the 2016 election, which included hackers affiliated with Russian military intelligence infiltrating Democratic National Committee emails and spreading false information on social media about Hillary Clinton.

The Defense Department conceded that it needs to adapt to a changing threat landscape and has strengthened U.S. Cyber Command and the National Security Agency, units actively waging covert programs to try to stop Chinese, Iranian and Russian hackers. It could be that physical American military infrastructure abroad is relevant in this regard.

But the threat from cyberattacks remains grave and growing.

From 2005 to 2020, the U.S. government, public networks and private companies were targeted in cyberattacks 135 times by Chinese, Russian and other state actors, according to the Council on Foreign Relations.

'Physics is physics'

To be sure, the U.S. faces major traditional military threats as well as intense competition from authoritarian foes in China and Russia.

There is the potential for American adversaries in Iran and North Korea to develop nuclear weapons and target the U.S., or for foreign militant groups to attempt a terrorist attack on U.S. soil reminiscent of 9/11.

U.S. military spending and overseas bases are a legacy of post-World War II leaders who decided to "never again allow the U.S. to ignore a problem until it comes to our doorstep," said Spoehr, the former Army lieutenant general.

He said that by placing U.S. troops around the world, whether in Iraq or Italy (home to more than 14,000 American military personnel), there is a "tripwire effect" that demonstrates American resolve to defend allies and, chiefly, itself.

Many policymakers and military officials agree that the large overseas military presence is about deterrence. They argue the U.S. requires a strong military able to quickly react to crises in difficult-to-access places.

"Physics is physics. That's not changed," said Breedlove, the former NATO commander.

"A U.S. fighter aircraft, even stationed in Italy, takes many hours and aerial refueling to fly to most places in Africa. They don't magic from one point to another," he added, referring to U.S.-led counterterrorism activity in Africa, the Middle East and beyond.

Breedlove said that since 2012, when U.S. Ambassador Christopher Stevens and three other Americans were killed in a terrorist attack on the U.S. mission in Benghazi, Libya, the Pentagon has reaffirmed its view that it needs U.S. troops "close to a problem." A House Select Committee report on the episode concluded the U.S. military was too slow to respond to the assault.

After 9/11, 'so much blood and treasure'

For some, the benefits of a large foreign military presence easily outweigh the costs.

"If the price of preventing another 9/11 is keeping some troops in Afghanistan or elsewhere indefinitely, I'd say that's a good investment for the American people," said Bowman, the former West Point professor. "If, on the other hand, our goal was to create a Switzerland in Afghanistan, we obviously failed. However, that was never the goal."

Afghanistan is a particularly hot flash point in this debate.

The 19-year-old conflict has cost more than $2 trillion and more than 2,300 American lives. More than 38,000 Afghan civilians have been killed. And yet the Taliban controls vast swaths of the country, which continues to be wracked by violence despite U.S.-brokered peace talks.

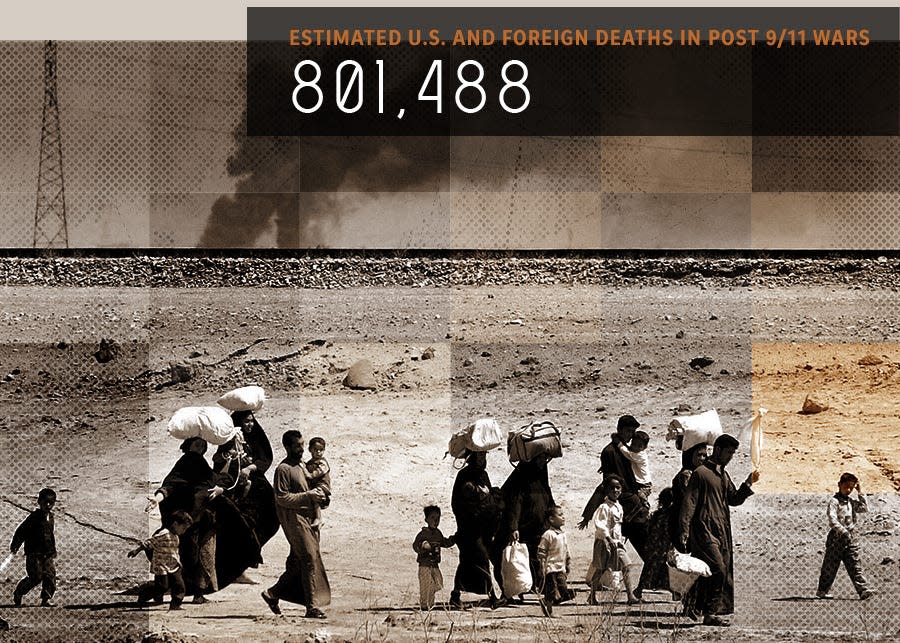

The toll in all major post-9/11 war zones over the past two decades is even more staggering. About 800,000 people – allied troops, opposition fighters, civilians, contractors, journalists, humanitarian aid workers – have been killed and 37 million people displaced, according to Brown's Costs of War project.

"In all these wars the U.S. has expended so much in terms of blood and treasure with actually very little to show for it," said Hartung of the Center for International Policy. "A reckoning is near."

It's difficult to point to a single location where a post-9/11 U.S. military intervention has led to either a thriving democracy or measurably reduced terrorism, he said.

For some, U.S. wars after 9/11 have complicated the legacy of America's status as a post-World War II guardian of international values and order, and they worry that U.S. military assertiveness can compound problems.

"To me, a national security threat is an existential threat to the homeland. In fact, from what I saw, the U.S. presence in Iraq exacerbated the threat to the homeland," said an American official who was a civilian contractor for Iraq's transitional government after the U.S.-led invasion in 2003. This person did not want to be named because of his current government job.

"All the dysfunction, the abuse, our inability to hold the country together. It made it worse," he said, referring to a litany of persistent allegations about the behavior of American soldiers in Iraq that include torturing prisoners and terrorism suspects. Many security experts believe this alleged behavior directly contributed to the rise of the Islamic State (ISIS) in Syria and Iraq.

Further, according to a report from the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington-based think tank, domestic right-wing extremists were responsible for almost 70% of terrorist attacks and plots in the U.S. in 2020, a figure that casts some doubt on the appropriateness of maintaining hundreds of military bases and tens of thousands of troops abroad in the face of a growing national security threat at home.

In the wake of the attacks at the Capitol on Jan. 6, the Biden administration has ordered a review of the threat from domestic violent extremism for precisely that reason.

The Defense Department referred USA TODAY's questions on national security to the White House. A national security official in the Biden administration said the White House had nothing new to share about overseas troop posture. White House officials in the former Trump administration did not respond to a request for comment.

In Washington, old habits die hard

"The U.S. needs to break with the 'world's policeman' concept," said Gates, who was defense secretary during most of the Iraq War under Presidents Barack Obama and George W. Bush.

Gates said the U.S. needs to "be modest about what it can accomplish through military force" and strengthen its diplomacy and "positive economic tools and instruments."

Even the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff recently said the U.S. should rethink its large permanent troop levels in dangerous parts of the world, where they could be vulnerable if regional conflicts flare up.

The U.S. needs an overseas presence, but it should be "episodic," not permanent, Milley said in December. "Large permanent U.S. bases overseas might be necessary for rotational forces to go into and out of, but permanently positioning U.S. forces I think needs a significant relook for the future,” Milley said, both because of the high costs and the risk to military families.

And yet, almost every attempt by former President Donald Trump over the past four years to deliver on his campaign promise to stop "America's endless wars" was met with fierce bipartisan backlash, with lawmakers citing the need to stand by America’s allies, check aggression from Russia and China, and keep terrorists at bay.

When Trump announced a drawdown in Syria, Republican Sen. Lindsey Graham, usually a Trump loyalist, called it "a stain on America’s honor." When Trump called for a redeployment of U.S. troops stationed in Germany, Rep. Liz Cheney, R-Wyo., denounced it as "dangerously misguided." And as Trump pushed for further withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan – American’s longest war – Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell warned that "premature" exit would be tantamount to surrender.

"It would be reminiscent of the humiliating American departure from Saigon in 1975," the GOP leader said, a reference to when then-North Vietnam handed the U.S. one of its most crushing military defeats.

Indeed, Biden may be inclined to reverse some of Trump’s military redeployment decisions, based on his own vision of American security shaped by four decades in Washington. Biden will almost certainly consider, for example, the repercussions of the Obama administration's decision to withdraw from Iraq in 2011, which helped create a vacuum for the rise of ISIS.

Even as Trump cut U.S. troops levels in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria to the bone, he also added at least 14,000 troops to the Middle East to confront Iran, a consequence of rising tensions after his administration's withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal.

And while it's not yet clear how many bases, if any, were shuttered under Trump, since 2016 he opened additional bases in Afghanistan, Estonia, Cyprus, Germany, Hungary, Iceland, Israel, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Niger, Norway, Palau, the Philippines, Poland, Romania, Saudi Arabia, Slovakia, Somalia, Syria and Tunisia, according to data from the Pentagon and Vine.

The U.S. Space Force, established by Trump in December 2019, already has a squadron of 20 airmen stationed at Qatar’s Al-Udeid Air Base, as well as overseas facilities for missile surveillance in Greenland, the United Kingdom, Ascension Island in the Pacific Ocean and in the Diego Garcia militarized atoll in the Indian Ocean, according to Stars and Stripes magazine, a U.S. military newspaper.

Drone warfare and questions of accountability

The Trump administration instructed the Pentagon to shift emphasis from counterterrorism and toward competition with China and Russia.

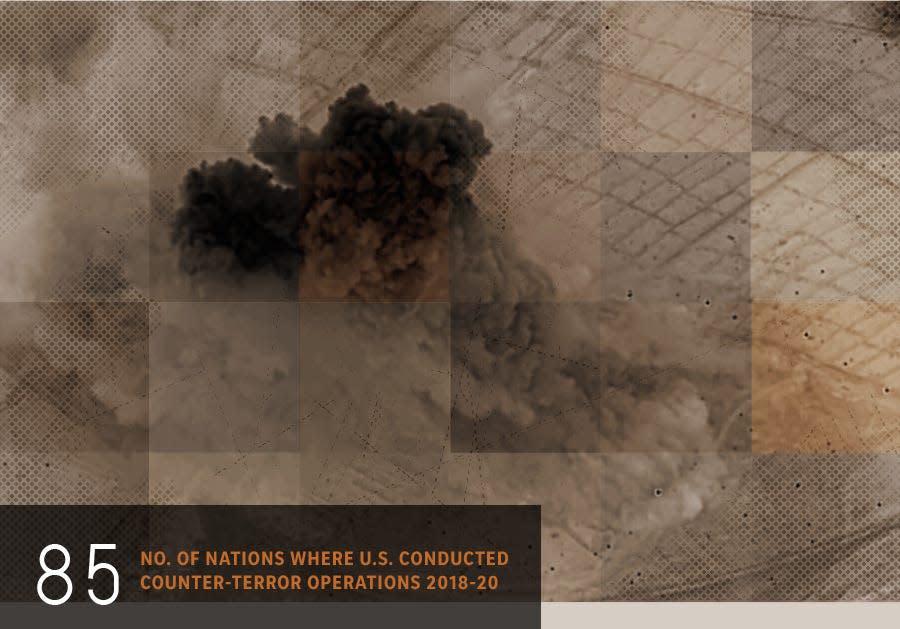

Whether or not Biden continues on this path, U.S. military activity from 2018 to 2020 shows there has not been a corresponding drawdown of counterterrorism resources and operations to meet that goal, according to research by Stephanie Savell, a defense and security researcher for the Costs of War project at Brown University's Watson Institute.

From 2018 to 2020, the U.S. military was active in counterterrorism operations in 85 countries, either directly or via surrogates, training exercises, drone strikes or low-profile U.S. special operations forces missions, according to Savell.

Even where the U.S. military does not have troops or bases, it uses proxies and drones to surveil and sometimes remotely launch missiles against suspected terrorists.

In 2019, the U.S.-led coalition backing the Afghan government against Taliban insurgents dropped more bombs and missiles from warplanes and drones than in any other year of the war dating to 2001. Warplanes fired 7,423 weapons in 2019, according to Air Force data. The previous record was set in 2018, when 7,362 weapons were dropped. In 2016, the last year of the Obama administration, that figure was 1,337.

Those foreign engagements have become less accountable, Savell said. Congress didn’t even know the extent of the U.S. presence in Africa a few years ago when four Army special operations soldiers were killed in Niger.

U.S. activity ranges from combat in Kenya to war games in Tajikistan and raises fresh questions about the meaning of ending "endless wars" if America's military is routinely engaged in foreign military theaters.

Critics say it is also evidence the Pentagon continues to use force in places that extend beyond the original intent of the 2001 Authorization of Military Force (AUMF), the law that sprung from President George W. Bush's "global war on terror" and the invasion of Afghanistan after 9/11.

That 2001 authorization has been stretched to target militant groups in Syria, Pakistan and the Philippines, as well as al-Shabaab in Kenya and Somalia and beyond.

Savell said the U.S. should consider whether there are "more effective, nonmilitary alternatives that cost fewer lives and less taxpayer dollars to address this security challenge."

Sen. Tim Kaine, D-Va., agrees.

"No member of Congress who voted for (AUMF) could have conceived that it would be used to justify action against groups that didn’t even exist yet in places like the Philippines and Niger," he said.

'Mini Americas,' mini resentments

America's military is also routinely criticized for waste.

One example: For more than 50 years the Pentagon was legally required to ship U.S. coal from Pennsylvania to Germany 4,000 miles away to heat its military facilities there despite Germany having one of the highest levels of energy efficiency among advanced economies. The official U.S. national security explanation was that it was dangerous for the Pentagon to rely on energy from Russia, but Pennsylvania lawmakers also saw an opportunity to subsidize a dying industry, according to a federal watchdog.

The "Coal to Kaiserlautern" program, as it was dubbed, ended only in 2019, according to Taxpayers for Commons Sense, a Washington watchdog group.

Dan Grazier, a former Marine Corps captain who served tours of duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, said that when deployed he often observed what appeared to be reckless and indefensible spending by the U.S. military, such as the shipping of outsize training equipment manned by expensive contractors to remote locations only for it to be hardly used.

Grazier, now a fellow at The Project On Government Oversight, which investigates federal waste and corruption, said he believes the U.S. is guilty of failing to see issues from the perspective of other nations.

"Put it this way," Grazier said: "How crazy do you think people in the U.S. would get if the Russians suddenly opened military bases in Canada? We would lose our minds over that. Yet that's exactly what we're doing by placing, for example, U.S. troops in the Baltic states in Europe" as part of NATO deployments.

In fact, while some analysts have argued that Russian territorial aggression in Ukraine justifies NATO expansion in Eastern Europe, others have concluded that were it not for the persistent buildup of NATO forces near Russia's borders, President Vladimir Putin may not have decided to occupy Crimea and other parts of Ukraine.

America's military reach can foment smaller resentments.

Mark Gillem, a former U.S. Air Force officer and now architecture professor at the University of Oregon, said large overseas bases amount to "mini-Americas": expansive, car-friendly, costly to run, and often plagued by negative environmental, social and geopolitical consequences.

"When the U.S. comes in and takes a lot of land it creates problems. In many places, people aren't necessarily anti-American. They are anti-American sprawl," Gillem said.

Back in Bahrain, the U.S. Navy's Fifth Fleet base helps to stave off disruptive Iranian activity on a vital trade route where ships transport billions of dollars worth of oil every day. It's not difficult to grasp the connection between sabotaged oil tankers and the price Americans pay at the pump. About 4,500 Americans are permanently stationed there.

"It's good for business. But all these Americans erase some of who we are, our culture," said a Bahraini man who was sitting with a group of taxi drivers in the shade of a tree observing the U.S. military personnel as they enjoyed some down time on "American Alley."

The man did not want to be identified for fear of it hurting his job. Many of his clients are Americans.

Contributing: Deirdre Shesgreen, Tom Vanden Brook; Graphics by George Petras; Photo illustrations by Veronica Bravo; Photos by AP, Getty images

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: US military budget: What can global bases do vs. COVID, cyber attacks?