The quahog holds a dear place in RI’s culture. Could its days be numbered?

Editor's note: This is the first story in a three-part series on the quahog's decline in Rhode Island.

WARWICK – David Ghigliotty works his bullrake into the bottom of Narragansett Bay, using the drift of his skiff to pull its steel tines through the sandy bottom in search of quahogs on a cold December morning.

Normally, he’d feel clams tumble into the rake’s basket, but with thick rubber gloves protecting his hands on this frigid winter day, he listens instead for the faint sounds of their shells clanging against metal in the water below.

“Did you hear that?” he says. “That’s one there.”

Ghigliotty rocks the handle of his rake up and down in an easy rhythm, lifting and tugging, lifting and tugging, relying on skills he’s honed over 42 years as a commercial shellfisherman.

After a few minutes, he flips the switch on a winch that pulls the rake head to the surface, swishing the basket back and forth in the water to clear out the muck before pulling it on board.

He dumps the contents onto a sorting tray. There are a few rocks, some jagged oyster shells, a couple of spider crabs that Ghigliotty tosses to a hungry seagull lurking nearby, and barely a dozen quahogs.

It’s a meager catch for all of Ghigliotty’s effort. Over and over that morning he brings up a basket, only to find it fractionally full.

Too often this is what it’s like to be a quahogger in Rhode Island now. By any measure, the industry is in decline. An experienced raker like Ghigliotty once could harvest 1,500 clams or more a day. Now, he considers 500 a decent day's work.

The number of commercial license-holders who go out on the water with any regularity is fewer than 200, about a tenth of what it was in the last big quahog boom 40 years ago. As for those who work year-round like Ghigliotty, there are no more than 100 left, and the vast majority are on the wrong side of 50.

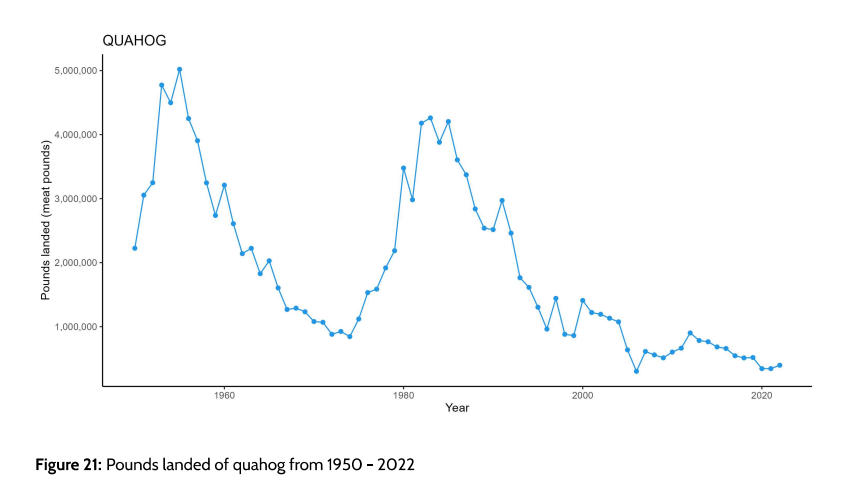

Harvests have followed a trajectory similar to license numbers, down to 397,000 meat pounds in 2022 from 4.2 million in 1985.

The situation has gotten so bad that the General Assembly formed a special commission last year to try to get to the bottom of what’s causing the industry’s decline – something shellfishermen had been asking legislators to do for years.

Six months into its work, the commission still doesn't have conclusive answers.

"I think we're at a pivotal point," said Rep. Joseph Solomon, the Warwick Democrat who created the commission. "Quahogging is such an important part of Rhode Island history. I don't want to see the tradition go away."

At the heart of Ocean State culture

Just as Narragansett Bay sits in the geographic center of Rhode Island, the Northern quahog occupies a place at the heart of Ocean State culture.

Known just about everywhere else it’s found along the East Coast as simply a hard clam, the quahog is to Rhode Island what the crawfish is to Louisiana or the blue crab to Maryland.

During the industry’s heyday in Rhode Island, the state was the top producer of quahogs in America, supplying as much as a quarter of the nation's total harvest. It’s no surprise then that the General Assembly named it the state mollusk, or that the quahog has lent its name to the fictional hometown on a certain TV show set in Rhode Island.

Digging for clams along the Rhode Island shore is an age-old tradition. No license is necessary for state residents who do it recreationally. Not even special tools are needed. Just dig down in the sand with hands or tread with your feet, like the land's original inhabitants did, and you may find the briny makings of a chowder or some stuffies.

But it’s the commercial license-holders who supply the larger market for restaurants and grocery stores, heading out on the water as regularly as the tides, armed with their long-handled bullrakes or equipped with scuba gear, to harvest from beds in the Bay.

Theirs is the only remaining commercial fishery of any real size in the Bay, and they worry that it could go the way of the estuary’s other wild fisheries: for soft-shell clams, which petered out before the turn of the 20th century; oysters, which hung on for a few more decades before the Hurricane of 1938 destroyed what remained; or scallops, which haven’t been seen in any real numbers since the last big seagrass beds died off in the 1950s.

All, to differing extents, were victims of pollution as what was once America’s most industrialized estuary became a dumping ground for sewage and industrial waste, its waters turning anoxic and turbid.

Ironically, it’s the ongoing cleanup of the Bay, part of a decades-long effort that has been widely hailed as a resounding success, that quahoggers are now blaming for the recent struggles of their industry.

They say that state-mandated reductions in nitrogen released by wastewater treatment plants around the Bay have essentially cut off the supply of fertilizer to nourish the growth of phytoplankton, the microscopic plants that filter-feeders like quahogs use for sustenance.

They see a straight line between cause and effect. With less food in the water, there are fewer quahogs in the mud.

Ghigliotty's adulthood charts the history of the shellfishing industry in Rhode Island over the last four decades, through all of the ups and the many downs.

"My life is the Bay," he says.

As he works aboard his skiff, he complains that the hardy creatures he could once count on to make a good living aren't as abundant as they used to be. As for the ones he does pull up, too many are starving. Beds that used to be packed with fat-bodied clams are now full of empty shells.

He plunges his rake back in the water. Perched happily on a work bench, the seagull cracks open one of the crabs.

“At least he’s happy,” Ghigliotty says.

Fish kill triggers change

Shellfishermen can narrow down to the day when they believe the tides turned for the worse for them.

On Aug. 20, 2003, more than 1 million fish, starved of oxygen, were found dead and dying in the murky, pea-green waters of Greenwich Bay. The fish kill was larger than anything that had been seen before in Rhode Island, the result of a perfect storm of circumstances.

The weeks leading up had been rainier than normal, and runoff washed human and animal waste into the Bay, providing an overabundance of nutrients to feed phytoplankton. When the resulting bloom exhausted its supply of food, the plants died off, sank to the bottom and decomposed, in the process using up all the dissolved oxygen in the water.

Meanwhile, giant shoals of young menhaden, driven into the Bay by predatory bluefish, had nowhere to go but the now-perilous shallows. They were seen gasping for air at the water's surface, but it would do no good.

The stench of their rotting bodies hung over the area for days.

It wasn't just menhaden that were killed. Among the dead were eels, crabs and millions of juvenile soft-shell clams.

A report by the state Department of Environmental Management blamed the Greenwich Bay fish kill on excess nutrients in the water, a type of pollution that environmental advocates say is among the greatest threats to the health of Narragansett Bay. Human sources were found to be responsible for the episode, chiefly discharges from sewage treatment plants.

Scientists had been tracking low-oxygen conditions in the Bay for years and knew there was a connection to the plants, but the fish kill finally galvanized action.

The General Assembly responded with the passage of a law mandating a 50% reduction in nitrogen in the effluent from treatment plants by 2008. Within a year of enactment, the 11 treatment plants that empty into the upper Bay made the first reductions, totaling 30% of the nitrogen. It took a few more years to settle appeals and negotiate new permits, but by 2013 total levels of nitrogen discharges had been cut by 60%.

The impact on the Bay was nearly immediate. The water became clearer and there were fewer low-oxygen days. Additional changes carried out around the same time affecting overflows of runoff and sewage cut bacteria levels in the water in half.

“In my mind, this was a great, great thing to do,” University of Rhode Island oceanographer Candace Oviatt, a foremost expert on the Bay, told the special Quahog Commission at one of its first meetings.

But shellfishermen argue that at the same time the mandated cuts in nitrogen were achieved, the current dip in harvest numbers began. Over the last decade, landings have dropped by more than half.

“The data do not lie,” said commission member James Boyd, a longtime official with the state Coastal Resources Management Council, who went back to quahogging after he retired.

Many factors could be affecting low harvests

Regulators with the DEM and marine scientists, however, say the connection isn’t so clear-cut.

For one thing, the drop-off in harvests since 2012 is part of a much longer decline that predates by several decades the passage of stricter wastewater rules.

Even the notion that quahogs are less abundant is in dispute. The DEM has been counting and measuring quahogs around the Bay since the 1990s, and the results don’t show a reduction in numbers.

A study looking at shell growth rates found no statistical difference in quahogs harvested before and after the nitrogen reductions. And recent research has found that the Bay’s quahogs are in good health and recovering well after spawning.

It’s important, too, to keep in mind the historical record on nutrient levels. Scientists have estimated that the amounts of nitrogen in the Bay before the Industrial Revolution were about a quarter of what they were in the late 20th century, and yet there are records and anecdotal evidence of healthy stocks of quahogs, lobster and other animals in the Bay. Even with the recent reductions, nutrients are still above historical levels.

The shrinking of the quahog fleet also can’t be ignored. While shellfishermen say their numbers are down because there are fewer quahogs in the Bay, it’s also axiomatic that fewer people digging for quahogs should lead to lower harvests.

And then there’s the fact that quahog landings have slumped all along the Atlantic Coast. Harvests are down in Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey and Virginia. Total numbers in those states and Rhode Island in 2010 were a quarter of what they were in 1950.

In fact, other shellfish – soft-shell clams, oysters and bay scallops – are also seeing similar declines, according to one study. While the authors didn’t find definitive causes, they drew a link to climate change, specifically to warming winters caused by a shift in Atlantic Ocean currents and resulting impacts on food availability, reproduction and predation.

"I think it’s larger than just Narragansett Bay," Conor McManus, chief of the DEM’s Division of Marine Fisheries, said to the commission. “The signals that we’re seeing are not unique to the Bay.”

Rhode Island's long history of quahogging

In many ways, Narragansett Bay is the perfect home for quahogs.

Its coves and inlets offer shelter they need from rough seas. It has soft-bottom areas of sand and mud that they can bed down in. Its waters, fed by nine river basins, have a lower salinity than the open ocean, also just right for them.

And all those rivers, combined with currents from the deep ocean, mean there’s always been a steady natural stream of nutrients into the estuary. These nutrients fuel a beneficial bloom of phytoplankton in late winter and early spring, the tiny plants exploding in number and ensuring an ample supply of food that quahogs, waking from their winter slumber, can siphon from the water and trap in their gills as they prepare to spawn.

When the first Europeans arrived in the New World, they found coastal waters teeming with life. Ringed by salt marshes, its bottom covered in thick beds of eelgrass, the Bay was full of salmon and striped bass, eels, shad, alewife and mussels. In the 1635 account of his travels, William Wood wrote of foot-long oysters, 20-pound lobsters and “clamms as bigge as a pennie white loafe.”

Although quahogs had been harvested from the Bay for thousands of years – studies of shell middens prove so – the commercial fishery in Rhode Island is relatively young. It was first recorded in the 1870s, according to the National Marine Fisheries Service, when shellfishermen rowed to nearshore beds in the Bay and went to work with tongs, tools with baskets on the ends that scooped up quahogs when their long handles were scissored together.

As the Bay’s oyster industry collapsed, quahogging started to fill the void. The fishery took off during World War II with the addition of boats that towed dredges underwater.

At the all-time peak, in 1955, annual landings were nearly 30 times what they were just a few decades before.

Concerned about depleting the fishery, regulators banned dredges the following year. That decision, combined with the closing of the Providence River to shellfishing a decade earlier because of pollution, would lead to a steady drop-off in harvests in the ensuing years.

Passage of the Clean Water Act in 1972 reversed the decline. As areas of the upper Bay reopened, landings rebounded. Introduction of the modern bullrake and scuba gear also helped, allowing shellfishermen to reach deeper beds than they could with tongs.

The world's largest outboard motor fishing fleet

A bronze statue of a quahogger stands proudly atop a fountain beside the Warwick Public Library. Eight feet tall, with a bullrake in one hand and a bag of clams in the other, it’s a reminder that the heart of Rhode Island’s quahogging industry is found in this community, which boasts more miles of shoreline on Narragansett Bay than any other.

Ghigliotty grew up in the city’s Apponaug neighborhood, a stone’s throw from the water. His grandfather owned a boat. When he was a boy, Ghigliotty would beg to go clamming. At 15, he bought his own skiff and paid the $20 fee for his first commercial quahogging license.

“I still have it today,” says Ghigliotty, who’s now 57.

He went to Toll Gate High School and would stare longingly out the top-floor windows at the Bay in the distance. He tried going to technical college after graduating, but all he really wanted was to be a quahogger. So, when he was 18, raking for clams became his full-time job.

The early 1980s were boom times for the industry. Harvest numbers were rocketing skyward, nearing the highs of the '50s. Demand was so furious that seafood dealers would send their own boats out to the fleet to buy clams. They’d advertise their prices on placards, and sometimes a bidding war would ensue on the water.

With 3,000 commercial license-holders plying the Bay for quahogs, it was said they made up the largest outboard-motor fishing fleet in the world. Recession swelled their ranks, with men laid off from other professions. Shellfishing was an easy alternative. All a person needed was a skiff and a bullrake.

“There were so many boats you could walk from one side of the Bay to the other,” Ghigliotty says.

It was like the Wild West. With throngs of quahoggers and only so many beds to harvest, fistfights would break out over the best spots. There were newspaper stories of boats ramming each other, and even one report of a couple of rakers dropping pipe bombs onto divers in the waters beneath them.

After the reopening of Barrington Beach and other once-contaminated areas rich in clams, Ghigliotty could make several hundred dollars or more a day. It was hard work, but it didn’t matter.

“I loved it,” he says. “I really loved it.”

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Quahogs in Rhode Island may be disappearing. No one seems to know why.