Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter Denny Walsh, a longtime Sacramento Bee writer, dies

Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter Denny J. Walsh, who spent more than 25 years covering federal courts for The Sacramento Bee after a career that included stops at Life magazine and The New York Times, died Friday. He was 88.

Walsh, a giant in American journalism who relished complex investigative stories exposing corruption among public officials and wrongdoing by mob figures, died in his sleep at his Antelope home, five months after the death of Peggy, his wife of 57 years.

He retired from The Bee in November 2016, but maintained close contact with a legion of judges, lawyers and former colleagues who said he frequently knew more about the inner workings of the federal courts in downtown Sacramento than the participants themselves.

“He expected much from those of us who sit on our federal trial court, and he paid very close attention to what we were doing and the cases we handled during the long time he occupied a special perch — his very own press office in our building, first at 650 Capitol Mall and then here in the Matsui Courthouse at 501 I Street,” Chief U.S. District Judge Kimberly J. Mueller said. “I would have lunch with Denny periodically to find out what was really happening here, and I will miss those lunches terribly.”

Walsh had a fierce devotion to detail and a photographic memory that gave him the ability to sit through hours of court hearings taking notes only sparingly, then reproduce lengthy — and accurate — quotes for his stories.

As an investigative reporter — a term he loathed because he believed all reporting involved investigation — he was fearless, a trait that led to him being sued for libel unsuccessfully numerous times.

He recalled at his retirement ceremony in 2016 that Time magazine once labeled him the “most sued reporter in America,” and accounts from his time at Life say he was sued 52 times while reporting for the magazine. He prevailed in every case.

His focus on organized crime reporting once led to him and his family being placed in protective custody in Southern California by federal law enforcement officials after a death threat against him by mob figures.

And he had little patience for editors he thought were hesitant to publish some of his work, a characteristic that led to his 1974 firing from The New York Times and eventually sent him west to work for The McClatchy Co. and C.K. McClatchy, then president of the company that published The Sacramento Bee, The Fresno Bee and The Modesto Bee.

“He was a terrific reporter, as good as you can get,” said Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter Seymour Hersh. “I don’t think they quite knew how good he was.”

Drawn to reporting by a movie

Denny Jay Walsh was born Nov. 23, 1935, in Omaha, Nebraska, to Gerald Jerome Walsh, an auto mechanic, and Muriel Almeda Walsh, a beautician. The family moved to Southern California during World War II, where his parents worked in the defense industry, and later settled in Horton, Kansas.

As a teenager, Walsh was drawn to journalism while working part-time as a projectionist at the Liberty Theater, where he repeatedly watched the 1952 movie “The Turning Point,” which starred William Holden as a crusading reporter.

“He said that he watched that movie at every showing and that he was captivated by it,” said Sacramento attorney Stewart Katz, a longtime friend.

(Years later, as Walsh was traveling in Africa in 1967, a friend arranged for Walsh to meet Holden at the Mount Kenya Safari Club. Holden did not seem thrilled with the evening, Walsh later recalled, writing that he was “awed and inhibited” by the actor and did not mention to Holden why he had become a reporter.)

He enrolled at the University of Missouri, but dropped out to join the Marine Corps in 1954 and served until 1958, when he returned to college and graduated in January 1962.

During summer breaks, Walsh worked as a Los Angeles cab driver, an experience that did little to improve his aggressive and inattentive driving style.

He landed a reporting job at the St. Louis Globe-Democrat and married his first wife, Angela Sharp, in 1960. They had two daughters before the marriage ended in divorce in 1964, something Walsh blamed on the long hours he spent at work.

In 1969, Walsh and his reporting partner, Albert Delugach, were awarded the Pulitzer Prize in local investigative specialized reporting for stories exposing “fraud and abuse of power within the St. Louis Steamfitters Union, Local 562.”

Delugach, who died in 2015, and Walsh both left the newspaper after an editor refused to run another investigative piece, Walsh said years later. He also recounted how he gave the story to The Wall Street Journal before leaving the Globe-Democrat.

‘A reporter, first, last, and always’

While Walsh worked in St. Louis, he met a young editorial writer, Pat Buchanan, who would later become an assistant to President Richard Nixon and eventually run for president.

Walsh and Buchanan became roommates and drinking buddies during their time in St. Louis, and in his 1988 memoir, “Right from the Beginning,” Buchanan recalled Walsh as “a reporter, first, last, and always.”

“When Walsh sank his teeth into a politician, he usually did serious damage, and he was always reluctant to let go,” Buchanan wrote.

Buchanan also recalled Walsh’s penchant for getting himself sued, writing that when Walsh was an usher at his wedding in 1971 Walsh was then being sued by the governor of Ohio for $6 million and the mayor of St. Louis for $12 million.

Buchanan wrote that he asked Walsh how he could afford such financial peril on a reporter’s salary.

“Oh, Pat, you can make it if you just put a little bit away every payday,” Walsh replied.

After leaving St. Louis, Walsh joined an investigative team at Life magazine and later worked in the Washington, D.C., bureau of The New York Times.

Hersh, who won a Pulitzer for his exposé of the My Lai massacre during the Vietnam War, recounted in his 2019 memoir “Reporter” how Walsh helped him during coverage of the Watergate scandal by connecting him to an old friend who was “high up in the Nixon world.”

“Out of the clear blue sky Denny just said, ‘You know, I’ve got a friend you should call,’ and he put me into the game,” Hersh said in a phone interview Sunday. “He helped me, and that’s what Denny does.

“It’s not just something up his sleeve, it’s something really good up his sleeve.”

Hersh wrote in his book that Walsh was “a wonderful reporter — careful, meticulous, and an expert on organized crime and political corruption.”

He also recalled how Walsh was fired in 1974 by Times Managing Editor A.M. “Abe” Rosenthal after the newspaper refused to publish a lengthy political corruption investigation Walsh was writing.

“They didn’t understand what a good reporter he was, that’s all,” Hersh said. “He just worked differently from the others. He was quiet, didn’t kiss ass in any way with anybody, and I had his back and he had my back.”

Following his firing, Walsh was hired by C.K. McClatchy to head an investigative team for the chain’s California newspapers, and Walsh would soon find himself the target of two huge libel suits, one a $6 million suit filed by a Fresno developer, the other a $250 million lawsuit filed by Nevada Republican Sen. Paul Laxalt.

The Fresno lawsuit was settled after The Sacramento and Fresno Bees ran a “clarification,” and the Laxalt lawsuit was dismissed.

Like out of a novel

Walsh later was assigned to cover federal courts, where he became a familiar figure “walking my post,” as he described his daily routine of reading every court filing and keeping watch over the courtrooms.

He would linger late into the evening in the cramped press room he occupied next to the clerk’s office, where he surrounded himself with enormous stacks of legal documents and newspapers and nurtured his long list of sources.

“He was like out of a novel,” said veteran investigative journalist Lowell Bergman, who first met Walsh in 1970. “In certain ways, it was like, where’s Denny Walsh? Well, you walk into the courthouse and everybody knows, ‘just go to the clerk’s office and he’s there.’”

His ability to find — and maintain — sources for his stories was legendary.

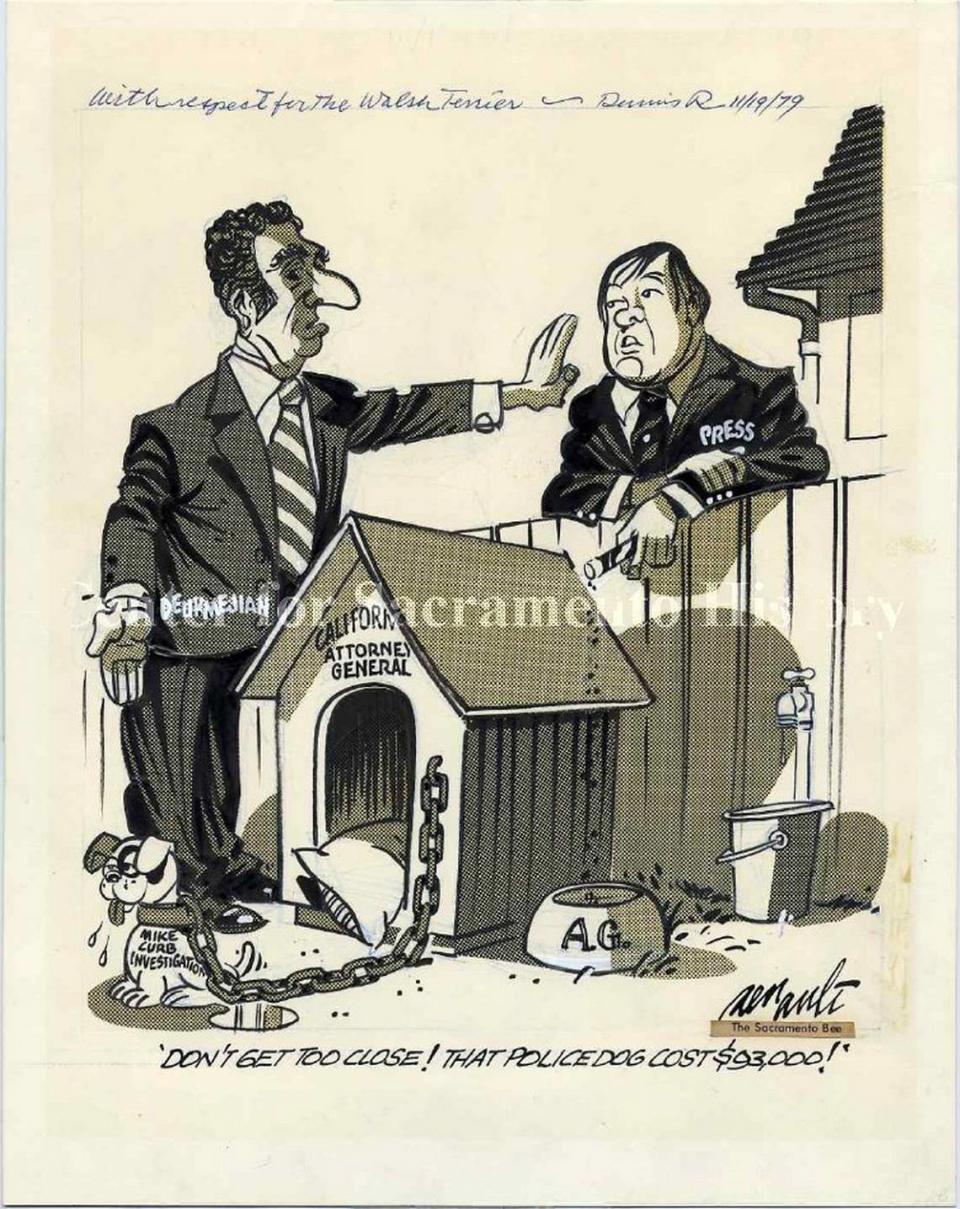

One night, needing clarification on a story he was working on, Walsh made a direct call to the office of a longtime acquaintance: California Gov. Jerry Brown.

He identified himself and was put through without delay.

A lifelong baseball fan, he sometimes found time to slip away with a judge for a trip to see the San Francisco Giants or the Sacramento River Cats.

But his focus was on what was going on inside the courthouse, and Senior U.S. District Judge William B. Shubb described him in an interview Monday as “the quintessential newspaper reporter.”

“Denny never wanted to call himself a ‘journalist,’” Shubb said. “He was a newspaper reporter.”

The judge said Walsh had the ability to report on complex legal opinions and explain them to readers.

“It’s very important that the public understand what we do,” Shubb said. “We don’t have a PR department.

“All we want is our opinions to be accurately communicated to the public, and nobody did that better than Denny Walsh.”

Shubb said the judges were so appreciative of his abilities that when Walsh retired they paid out of their own pockets to have a plaque made for him featuring a scroll inscribed with the First Amendment.

“It wasn’t because he said something nice about us, it was because he said something accurate about us,” Shubb said.

His daughter, Colleen Bartow, said her father loved watching football and baseball, and spent years as an umpire at Little League games.

“He was a huge movie buff and a lover of classic country music,” she recalled. “He loved his family and friends and all the dogs he ever had.”

Walsh was a devoted fan of Merle Haggard, attending numerous Haggard concerts with his longtime friend, defense attorney Tim Zindel.

His office walls were dotted with photos of Haggard, and on Friday afternoons he could be found unshaven and tie-less there working as his stereo blared loud country tunes into the courthouse corridors.

The Unabomber, terror cases and corruption

And he continued to break story after story.

Walsh covered the case against Unabomber Theodore Kaczynski, broke the news of the federal government charging a Hmong general and an American officer from Woodland with plotting to overthrow the government of Laos, and reported in 2005 that federal officials were claiming they had broken up an al-Qaida terrorist cell in Lodi.

The Laos plot case was later dismissed, and the claims in the Lodi case were criticized as overblown, with a former Lodi cherry-picker convicted in the case having his conviction vacated in 2020.

Walsh once noticed some missing pages in a voluminous court file involving California Coastal Commission member Mark Nathanson, who went to prison in 1993 for extorting payments from people who wanted permits to build on the coastline in Southern California.

Walsh discovered the pages had been ordered locked in a courthouse safe by U.S. District Judge Lawrence K. Karlton, and Walsh and The Bee waged a fight that led to the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ordering the release of unredacted documents that had been withheld.

The documents revealed allegations that then-Gov. Gray Davis had been accused of seeking help from Nathanson for campaign contributors, something Davis adamantly denied.

At one point Walsh’s sourcing was so solid he ended up under investigation by a team of FBI agents from Los Angeles who were dispatched to determine — unsuccessfully — how he had broken a story from supposedly sealed court documents.

An empty accordion folder labeled “Federal Investigation of Walsh” in his handwriting still rests in his office as the only clue that such a probe took place.

Despite his achievements, Walsh rarely spoke about the journalistic prizes he had won, preferring instead to regale colleagues and sources with tales of the characters he met over the years or to talk about his dogs, animals he adored.

He gave up drinking and cigars years ago and, by the time he retired, he had lost one eye and one lung to illness — but refused to slow down.

He maintained his contacts with the lawyers and judges he had come to know and fostered a keen interest in the workings of the courts in the Sacramento-based Eastern District of California. His last piece for The Bee was a freelance column that ran on Christmas 2016 and was devoted to the 50-year history of the Eastern District.

He spoke about writing an autobiography, but discovered after retirement that years of notes he had kept were on computer files that had become corrupted and could not be retrieved.

Despite that, Walsh maintained his interest in news coverage of politics and the judiciary, and in January attended an evening at KVIE-TV featuring a discussion with Bergman.

“I’m somebody who has gotten in trouble with his publisher or broadcaster or with some of the people who took umbrage about what I was going to report,” Bergman said Saturday. “Denny was kind of unusual in that he seems to get in as much trouble as I did.”

Walsh is survived by two children, Bartow of St. Louis and Sean Walsh of Sacramento, who recalled his father as loving and supportive, and seven grandchildren. His eldest child, Catherine, died in February.

Walsh’s family is planning a memorial service for May, and friends wanting to post memories or photos of Walsh can do so here.

“My dad was, always has been, and always will be one of my favorite people,” Bartow said. “I feel so incredibly lucky to have had him as my father.

“He could tell a story like no other.”