As President Joe Biden steps aside, is America ready for President Kamala Harris?

Kamala Harris has been on a yo-yo string with Democratic Party bigwigs since that cataclysmic debate performance catapulted her boss out of a sure 2024 nomination.

Weeks before President Joe Biden stepped aside – and swiftly endorsed Harris to be the 2024 nominee – the vice president had emerged as the most logical replacement to top the ticket after Biden wore his frailty on national TV.

Allies disseminated a logic about why Harris would be the natural successor: She could seamlessly inherit the campaign's massive warchest; her law enforcement background is best suited to prosecute the political case against Republican Donald Trump; polling shows she can win; and having been the nation's first multiracial and woman VP could galvanize a new generation of younger progressives.

But from the start, there has been a hesitancy to fully embrace the country’s second-in-command, with some Democrats openly overlooking her. When a group of 24 former House Democrats sent Biden a letter last week lobbying for an open convention in August, it made no mention of Harris.

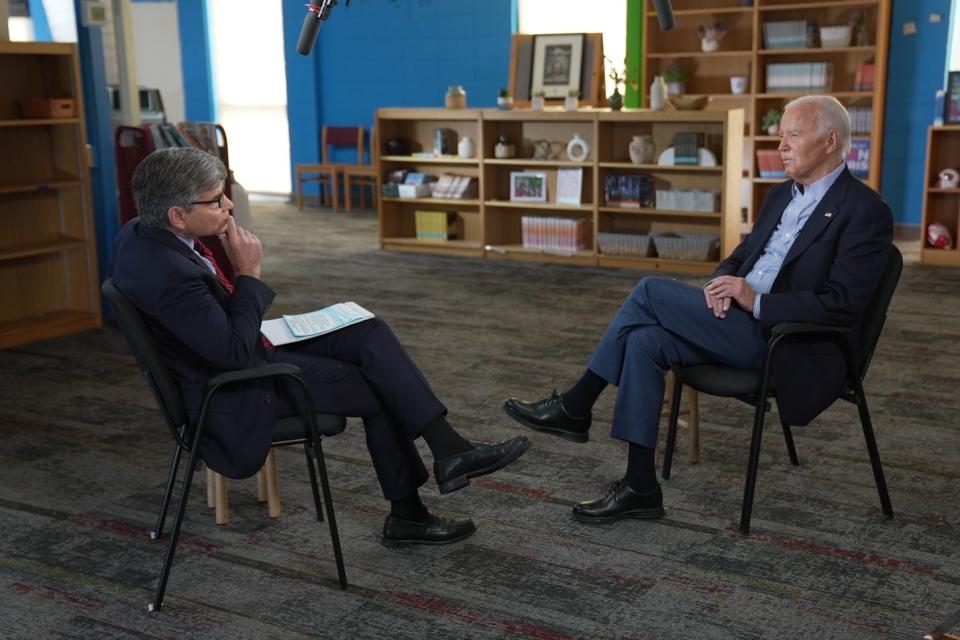

The day after Biden found himself fighting for his future in an interview with ABC News’ George Stephanopoulos, Harris was asked to assure Black women, the party’s backbone, that the U.S. wouldn’t take a step backward in this election on issues they care about, including economic and reproductive freedom. Her message was far from reassuring.

“Here’s the thing about elections,” Harris told a moderator at Essence Festival of Culture in New Orleans on July 6, during a discussion entitled “Chief to Chief.” “The people who make decisions at that level often will pay attention to either who’s writing the checks or who votes. That’s a cold, hard reality.”

Recent history: Kamala Harris on standby as Democrats plunge into panic mode

The 59-year-old Harris may seem the obvious strategic page turn for the party as well as a generational shift. Her life has been an acrobatic twist and turn, filled with personal challenges and accomplishments, including political tests in her home state of California similar to what she and the country face now.

But some wonder whether a country bitterly divided by cultural issues around race, gender and family – already seemingly poised to return Donald Trump to power – is ready for a woman of color to sit in the Oval Office.

“Black women are judged more harshly by the right, by the left – by everyone,” said Aimy Steele, founder and CEO of The New North Carolina Project, which is dedicated to expanding voter engagement and access in the Tar Heel State.

Steele said beyond race and gender, there are other parts of Harris’ life that she believes liberal allies will fail to accept or defend, including that she is a professional woman who went unmarried most of her life and put her career first without having biological children.

“I think we’re kidding ourselves to really believe that we are, even on the progressive side, in a post-racial democracy or a place where these types of things don’t matter,” said Steele, who unsuccessfully ran for the North Carolina legislature in 2020.

Halie Soifer, CEO of the Jewish Democratic Council of America, told USA TODAY that’s “all the more reason to make sure that we stand with her. We need to stand for something.”

“Misogyny, racism and other forms of bigotry are going to exist in this country, and yes, they may even be exacerbated by having a woman of color at the top of the ticket,” said Soifer, who served as a national security adviser to Harris in the Senate.

“But that is absolutely not a reason to cower or to allow the fear of that hate to impede progress in this country, and that’s actually been driving Kamala Harris her whole career.”

Other progressives still bruised by the political backlashes from the Barack Obama years emphasize that they concur: Harris is the face of the country’s future. The U.S. is projected to be majority people of color by 2045.

Trump and other Republicans have long been aware of the possible ticket switch, and have derided Harris as incompetent, socially awkward and responsible for chief failures in the Biden administration. GOP officials suggest that’s only the beginning.

“We’ve not really gone into depths with the record of Kamala Harris,” Rep. Byron Donalds, R-Fla., said in a Fox News Sunday appearance this month.

At the Republican National Convention last week, former Republican presidential candidate Nikki Haley reminded delegates she had predicted Democrats would look to pass the baton to Harris in the middle of the 2024 contest.

“For more than a year, I said a vote for Joe Biden is a vote for President Kamala Harris,” she said. "After seeing the debate, everyone knows it’s true. If we have four more years of Biden or a single day of Harris, our country will be badly worse off."

Dems not fully sold on Harris either

Harris’ opposition is not only coming from the other side of the aisle, as Democratic skeptics worry about her viability.

A former Harris staffer wrote in The Atlantic this month “an automatic coronation of Harris would be a grave mistake.” She argued for a process to battle-test her against others vs. Trump; and said supporters are too quick to write off viability concerns as “racist and sexist.”

A new AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research survey released this past week found 58% of Democrats believe Harris would make a good president. But the poll shows 22% of Democrats don't think she would versus 20% who said they don’t know enough about her.

Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y., warned in a Instagram live Thursday it would be incorrect to think there is a consensus among Democrats that Harris will get the support of people who wanted Biden to leave.

Those individuals, she said, “are interested in removing the whole ticket.”

Other progressives, however, warn that backing away from Harris could be disastrous for the party. Democratic strategist Bakari Sellers summed it up in a post on X: “Skip over Kamala Harris at your own peril.”

A child of immigrants with a fierce, ‘extraordinary’ mother

Harris was born in Oakland, Calif. in 1964 amid the Civil Rights Movement to immigrant parents – her father Donald Harris, was an economist born in Jamaica and Shyamala Gopalan, was a cancer researcher from India.

In her 2019 memoir, she briefly describes her parents’ marriage falling apart when she was five, leading to divorce. She only saw her father during summers in Palo Alto when he taught at Stanford, and acknowledges she was shaped by her 5’1” mother, whom she calls “extraordinary.”

Her mother took a teaching job at McGill University when Harris was 12, moving her and her sister to Montreal from 1976 until she graduated from high school in 1981.

It was in Canada where Harris first developed an affinity for lawyers who broke barriers such as Thurgood Marshall, Charles Hamilton Houston, Constance Baker Motley – giants of the civil rights movement, she wrote.

Harris returned to the states to attend Howard University where she flourished in the environment where “everyone was young, gifted and Black.” She pledged Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc., the second founded of the historic “divine nine” Greek-lettered organizations among African Americans. She interned at the Federal Trade Commission; researched at the National Archives and was a tour guide at the U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing.

She first entered politics as a staffer for Democratic Sen. Alan Cranston, of California, and then returned home to Oakland to U.C. Hastings College of Law and graduated in 1989.

Harris revealed in her book she took the California bar exam that July and “to my utter devastation, I had failed,” an acknowledged setback for a self-described perfectionist. She passed in February 1990 and began work at the Alameda County District Attorney’s Office.

Her political star began to rise in 1994 with her relationship with Willie Brown, the legendary California politician who at the time was the statehouse speaker, married – although long separated – and 30 years older than Harris.

California entrepreneur Trevor Traina, a longtime Harris friend and former U.S. ambassador to Austria, said that relationship was a politically formative one.

"Kamala’s a warm person who has a lot of charm and charisma. And she is the protégé of Willie Brown, who is the king of charm,” Traina said in an interview with USA TODAY. “And I think she learned well from him.”

Influential San Francisco Chronicle gossip columnist Herb Caen first put her name in print that March as Brown and Harris were spotted around town.

Their romance continued to raise eyebrows that November when Brown named Harris to a state medical board, along with a hefty salary. The affair ended in 1996, but the pair would be linked for decades and the subject of character assaults into the 2020 campaign.

Kristin Powell, principal of Black to the Future Action Fund, a national political advocacy group, said women in politics typically have their dating and sex lives dragged out in public as disqualifiers for higher office.

“The threats against her, in my opinion, will be astronomically higher than the ones against Obama because she’s a woman, not just a Black person, but a Black woman,” she said.

Powell said that same standard isn’t applied to men, noting that for years Trump has been accused of having extra-martial affairs and of sexual assault (which the former president vehemently denies).

By 2000, Harris moved to City Hall and quickly set her eyes on the city’s top prosecutor job, challenging incumbent Terence Hallinan in 2003. An archived radio debate from that election previewed the sharp-elbowed Harris in her first political battle focused on a backlog of 40 homicide cases.

“We are seeing an erosion of the criminal justice system, an absolute neglect of cases and they’re prioritizing politics over professionalism,” Harris said in the testy segment.

Harris’ campaign sent out mailers featuring the ten faces of previous San Francisco DAs stretching back to 1900. All male, all white. “It’s time for a change,” it read in block red letters.

She has continued to underscore the importance of U.S. leadership looking like the increasingly diverse country, including earlier this month at the Essence Festival of Culture, an annual mecca for Black women.

“Let us always celebrate the diversity, the depth and the beauty of our culture,” she said.

If the vice president were to become the first name on a Democratic ticket, political activists such as Powell believe it would be a game-changer in 2024.

“There would be a lot of excitement, not just for her, but when a Black woman gets to the White House, her or someone else, it will be a lot of excitement for women in this country because we deserve to have female leadership,” she said.

Yet, recent polling shows Harris doesn’t necessarily outpace Biden in terms of Black voter enthusiasm, which may indicate she is in a weaker position than some supporters assume.

More: Biden's support among Black women leaders still strong even as others jump ship

Quentin James, founder and president of Collective PAC, which is aimed at building Black political power, said the vice president’s identity is a chief engine of her popularity with racially diverse constituents, but that more sophisticated minority voters have a sharper grading curve.

“I definitely think that representation alone is not enough,” he said. “People are looking for the meat and substance, and not solely the identity.”

Powell concurs that excitement over a non-white, non-male candidate comes second to certain policy commitments, especially among those who’ve lived through the Obama era.

“We would applaud having a Black woman in the White House,” Powell said. “But before we get excited about whether that's Kamala Harris, we need to understand what she’s going to give us.”

Harris was California’s top cop

A decade before being elevated to the vice presidency, Harris demonstrated an uncanny ability to beat the political odds in a political landscape that, much like today’s national terrain, was dominated by aging white men.

Traina said more than any other time period, he believes Harris’ time as San Francisco’s district attorney is an instructive window into her leadership. He said the city is cosmopolitan and international, but also notoriously left-leaning ranging from mainstream Democrats to socialists.

“There's a tension between the center left and the far left, which I think mirrors the national scene right now for the Democratic Party,” Traina said. “And you have politicians who need to be elected and who need to be able to speak to the center, who understand how to navigate that environment, and Kamala is one of those people.”

She took aim at the California Attorney General’s office in 2010 after the incumbent, Democrat Jerry Brown, ran for governor to replace term-limited Republican Arnold Schwarzenegger. It was up to Harris to retain the seat for the Democrats, and that election season was an extraordinary one as well. It would become the nationwide sweep known as the “red wave.”

Political attacks on Harris included her decision as San Francisco DA to not seek the death penalty for a gang member who shot and killed a police officer.

On Election Day in 2010, the red wave broke. Republicans regained control of the U.S. House and reclaimed governor’s seats and statehouses nationwide. In the Harris-Cooley race, however, the vote turned out to be one of the closest in California history. Ballot counting took more than three weeks.

Ace Smith, Harris’ political consultant at the time, recalls how the San Francisco Chronicle initially declared Cooley the victor.

It was a “Dewey defeats Truman” moment. In the end, Cooley had to concede.

Author Dan Morain, a Harris biographer, points to the win as a formative episode, where national politicians took notice of the upstart from California. The red wave, he said, “stopped at the eastern slope of the Sierra Nevada.”

Smith called Harris a “supremely talented, charismatic person” who attracted voters despite being outspent. In an oral history with Capitol Weekly last year, he suggested the race turned on a debate stage where Cooley defended taking both a pension and a salary after retiring.

Harris’ tenure as California attorney general drew accolades from Obama, who cast her as a “brilliant” and “dedicated” campaigner.

“(S)he is tough, and she is exactly what you’d want in anybody who is administering the law, and making sure that everybody is getting a fair shake," Obama said at a 2013 fundraiser that is best remembered for the president’s commentary on her attractiveness. (He quickly apologized.)

After becoming attorney general, it was clear to many observers Harris was aiming for even higher office, taking cautious positions on hot-button issues – or no position at all.

That would become the basis of Morain’s book, “Kamala’s Way,” about her ascent to the U.S. Senate and ultimately the vice presidency.

“It’s about her way of operating, and it’s her path to getting to where she is,” Morain said. “She can be very tough, she can be empathetic, she can be cautious, she can be unsure of herself, but she’s very smart and quick on her feet.”

It’s in this period that a friend introduced Harris to an entertainment lawyer in L.A. who would become her husband. Doug Emhoff would become the first second gentleman and first Jewish spouse of a president or vice president. After they wed in 2014, Emhoff’s children Cole and Ella didn’t want to call Harris a stepmom and coined the phrase: “Momala.”

By January 2015 a new lane had opened. Longtime Sen. Barbara Boxer announced she would not seek reelection in 2016. That left two of Smith’s clients, Harris and then-California Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom, to hash out their political futures – which Smith has said was less dramatic than some have reported.

“That’s stuff of legends and myths, but not true,” Smith said in 2023. “And at the end of the day, (Newsom) wanted to be governor more than he wanted to be senator. She wanted to be senator… The good news was it was folks who knew each other well.”

In California’s primary system, where the top two vote-getters advance, Harris emerged as the winner to run against fellow Democrat Loretta Sanchez, an almost 10-year veteran of the House of Representatives. She sailed to a more than 20-point victory over Sanchez in the general election in 2016, with the support of Obama and his vice president – Joe Biden.

A combative prosecutor on Capitol Hill

Harris became only the second Black woman to serve in the Senate in history following Illinois’s Carol Moseley Braun, a victory that came amid a new kind of red wave: That same night, Trump defeated Hillary Clinton.

Harris arrived at the Senate primed for the conflict. Her maiden speech on the Senate floor laced into Trump’s nominee for education secretary and future Cabinet member Betsy DeVos.

She landed initial appointments to the Homeland Security and Intelligence committees, in addition to the Environment and Budget panels. A year into office, Harris’ legal background helped her secure a spot on the Senate Judiciary Committee, which gave her a platform to grill Trump’s judicial nominees.

She leaned into questions about special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into allegations of collusion between the Trump campaign and Russia and pressed future Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh on abortion rights.

“Can you think of any laws that give government the power to make decisions about the male body?” she asked Kavanaugh during the exchange.

Kavanaugh replied, “I’m not thinking of any right now, senator.”

The clip went viral.

Soifer, the former national security adviser, said those examples in the Senate underscore how Harris is uniquely positioned to be the Democratic nominee. Harris would be the most stark contrast with Trump at a time when women’s rights, particularly reproductive healthcare, is at the forefront.

“She’s a force to be reckoned with, and I would love to see her debate Donald Trump,” Soifer said. “She would eviscerate him.”

Several months after the Kavanaugh hearings, Harris announced she’d run for president. She had served in the Senate just two years. She had not yet written a single piece of legislation that became law.

But she also had never lost an election.

Sizzling debate performance, then presidential hopes implode

Naysayers are quick to point at Harris’ failed 2020 presidential bid, which closed up shop before the first ballots were even cast.

Harris declared in her birthplace of Oakland, near the hospital where she was born; the University of California, Berkeley, where her parents met; and a stone’s throw from where she had worked as a young district attorney.

She was running to protect America’s democratic institutions and healthcare access for all, she said, to check the white supremacists who descended on Charlottesville and to keep children out of cages at the southern border.

“People in power are trying to convince us that the villain in our American story is each other. But that is not our story. That is not who we are. That’s not our America,” she said as she stood in front of Oakland City Hall.

Harris caught the country’s attention when she went after Biden at the first Democratic debate that summer. She criticized the former vice president for comments he’d made about pro-segregationists he served with and shared with him what it was like to be bused to an all-white school.

“You also worked with them to oppose busing,” she said. “And, you know, there was a little girl in California who was part of the second class to integrate her public schools, and she was bused to school every day. And that little girl was me.”

Harris shot up in the rankings: she was in a tight race for second place.

But the momentum did not hold. Less than three months after the breakout moment, Harris’ campaign was sinking. She was down in the polls, and running out of cash. She’d burned through a $35 million war chest and her campaign was rife with infighting.

Harris made one of the most difficult decisions of her political career. With two months to go until the Iowa Caucus, she quit the race.

Smith, the political consultant who engineered Harris’ 2010 win in the face of the red wave, said bowing out of the presidential race in 2020 was the right call and led to her vice presidential nod, contrasted with Elizabeth Warren’s bid that dragged on.

“Sometimes,” Smith said in 2023, “the wisest political decision you can make is actually to realize when you're not being successful and get out.”

The calculus paid off: When Biden secured the nomination, thanks largely to African American voters, he chose her as his running mate.

Harris’ sharp debate skills served her well on Biden’s ticket. As then-Vice President Mike Pence tried to interrupt her, Harris delivered one of the most memorable lines of her political career that turned into an online sensation.

“Mr. Vice President, I’m speaking,” she told Pence.

“She’s a remarkable leader who inspires certainly all of those who have worked with her closely, but also now the American people, especially women and young women who look to her as someone who gives them a sense of empowerment,” Soifer said. “She’s a fighter.”

Some wonder: What has Kamala Harris done as vice president?

Harris' election to vice president as the first woman, Black person and Asian American to serve in the role was met with celebration.

That enthusiasm waned over the years as Harris fumbled early assignments, which supporters claim she was unfairly saddled with in the early days of the Biden administration.

The president tasked her with addressing the “root causes” of mass migration to the southern border – an area she had little to no expertise on as a senator or attorney general. Harris’ team had to bring in outside experts from nonprofit organizations that do work in the region to brief her.

On a trip to Guatemala that June, Harris came under heavy scrutiny for telling NBC’s Lester Holt she’d been to the U.S.-Mexico border. Neither she nor Biden had at that point. The White House stressed that was not her assignment – it was to work with Northern Triangle countries. Harris soon caved to political pressure. Within weeks, she visited El Paso, Texas, where she scolded Congress to “stop the rhetoric and the finger pointing” and pass immigration legislation.

The pandemic and the efforts the White House took to protect the president and vice president from getting COVID left Harris isolated and unable to travel frequently her first year in office. The problem was compounded as Biden and his advisers struggled with how to utilize her.

Those episodes were brought up regularly during the GOP convention in Milwaukee last week as Republicans prepared for a scenario in which Harris could be the Democratic candidate.

“When Joe Biden and Kamala Harris refused to even come to Texas and see the border crisis that they created, I took the border crisis to them,” Republican Gov. Greg Abbott said on the convention stage.

Other Republicans, such as Rep. Tom Emmer, R-Minn., accused the VP of enabling “criminals and rioters” during the protests following the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer.

Biden had served in the Senate for more than three decades before he became vice president. There was no existing schema for someone like Harris. She was a trained lawyer, who did a short stint as a senator.

“Most of that stuff is not transferable to the job of the vice president,” said Harris’ first communications director as vice president, Ashley Etienne. “So she figured out what are her strengths. And she’s over indexed on them.”

Harris finds her footing on reproductive rights, other liberal causes

It took the leak of a Supreme Court decision reversing Roe v. Wade for Harris to cut her own path. She’d worked closely with abortion rights advocates in California. She was in her element.

In a fiery speech the next day at an abortion rights gala, Harris reminded activists of her exchange with Kavanaugh.

“Those who attack Roe have been clear. They want to ban abortion in every state. They want to bully anyone who seeks or provides reproductive healthcare. And they want to criminalize and punish women for making these decisions,” she said.

Jason Williams, a professor of justice studies at Montclair State University in New Jersey, said Harris’ stepped-up presence in the wake of the Dobbs decision changed the perception of her role.

“That’s when we’ve seen in a very public way the power that she brings to this team,’’ Williams said. “Obviously when she's talking about anything in the judicial system that’s her own thing. That’s what she went to school for. That’s what she has worked (for) as… a prosecutor for so many years.”

Harris traveled the country, sounding the alarm. Democrats lost the House in the midterm elections but kept the Senate with her assistance.

The election-year victories finally offered Harris an issue area she could own. She reoriented her agenda around cultural issues such as gun rights and book bans. Her team launched a tightly controlled national college tour that was designed to amplify her message. Celebrity moderators appeared on stage with Harris as the VP fielded pre-approved questions.

Biden tapped her for bigger and better opportunities to represent the U.S. at overseas summits.

After Hamas launched a brutal, surprise attack against Israeli civilians on Oct. 7, Harris sat in on Biden’s calls with Israel Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Biden then sent Harris to Dubai to discuss the governance of Gaza after the war with Middle Eastern leaders.

There she delivered a searing statement about how Israel was conducting itself in the war.

“The United States is unequivocal: International humanitarian law must be respected,” Harris said. “Too many innocent Palestinians have been killed. Frankly, the scale of civilian suffering and the images and videos coming from Gaza are devastating.”

In March, she called for an immediate cease fire – remarks that were among the most pointed at that time from a member of the Biden administration.

'Already on the job:' VP role gives Harris an edge

The balance Harris would have to achieve as a presidential candidate is differentiating herself on these issues, while also taking credit for some of the administration’s accomplishments, such as student debt forgiveness and job creation.

She will have to sell herself – quickly.

“This would be the challenge: Can she communicate how much of a role she played in those kinds of outcomes?’’ said Ange-Marie Hancock, executive director of the Kirwan Institute at The Ohio State University and curator of the Kamala Harris Project, a consortium of scholars from the country studying the vice president.

Elaine Kamarck, a longtime Democratic National Committee member and expert on the party’s rules, told a group of Democratic activists during a Friday call that Harris has two major advantages: she’s already been vetted and she’s already on the job.

“We’re not going to, likely, have some surprise,” Kamarck said on the call organized by the group Delegates are Democracy. “None of the other candidates, great as they are – and some of them, I like very much, I might even like them more than the vice president – none of them have been vetted on a national stage.”

As a former prosecutor, many believe Harris also would not be intimidated by Trump, which could come with its own backlash.

“As a woman and as a woman of color, how aggressive can she be before people start having the reaction that she’s too aggressive,’’ said Debbie Walsh, director of the Center for American Women and Politics Eagleton Institute of Politics at Rutgers University. “Is that trope of the angry Black woman going to be thrown at her?”

While racist and sexist attacks aren’t new, Walsh is among those who expect them to ratchet up if Harris runs for president, alongside persistent questioning about ability and qualifications.

“It’s not going to be a walk in the park,’’ Walsh said. “We are not post-racism. We are not post-sexism. We’re still there.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Is America prepared to support Kamala Harris as president?