In a nod to history, Biden meets with Brown v. Board of Education families

WASHINGTON — It's been a decade since Cheryl Brown Henderson, the daughter of the namesake plaintiff in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education civil rights case, last stepped foot in the White House.

On her last visit in 2014, Henderson's family met the nation's first Black president, Barack Obama.

When the Kansas native and founder of the Brown Foundation returned this Thursday for a conversation with President Joe Biden and other families involved in the case, she'll be celebrating another milestone — the 70th anniversary of the May 17, 1954, decision that led to the desegregation of schools.

"I always like to say that schools were the battle, but society was the target," Henderson, 73, said in an interview with USA TODAY ahead of the meeting. "It began to dismantle other aspects of Jim Crow and Black codes."

The case became a catalyst for major civil rights developments, from the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to the Fair Housing Act of 1968. And nearly two dozen family members of plaintiffs and officials from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, which organized most of the related civil rights cases that came before the Supreme Court, are in Washington, D.C. to mark the occasion.

Then vice president Biden didn't get the opportunity to meet Henderson during her last visit. But in some ways, Thursday's meeting in the Oval Office was also historic and emblematic of the evolution the president himself has had on key civil rights issues.

Biden now faces an election that many in America see not as just Biden vs former President Donald Trump but as a view of the future vs. the past.

Some conservatives across the country have argued that efforts on diversity, equity and inclusion have gone too far— changing education standards, shaping decisions in hiring and altering cultural norms in ways they see as deviating from a more traditional America.

Progressives see the contest as a fight to preserve government protections for marginalized groups across the country, including people of color, LGBTQ people and others — and they have to look no further than the overturning of another monumental court case, Roe v. Wade, to point to how tenuous those protections may really be.

Henderson said her own message to Biden would be about the fragility of American democracy and the unfolding of the court's decision to overturn the "separate but equal" doctrine as unconstitutional.

"Right now, democracy is on the line. The White House is one of the symbols of democracy," she said. "Democracy gave birth to the rule of law, and the rule of law gave birth to Brown vs. the Board of Education."

One of the plaintiffs told Biden it should be a national holiday, Henderson said in a news conference with reporters following the meeting. To do so, would enable the country to learn more about the decision and commemorate it every year. The plaintiffs also asked the president to keep up his support for Historically Black Colleges and Universities.

"We're pleased that this administration is so diverse and looks like this country. We waited a long time," Henderson said they told him.

Alongside Henderson was Derrick Johnson, President of the NAACP, John Stokes, a Brown v. Board of Education plaintiff in the Virginia case and Nathaniel Briggs, the son of South Carolina plaintiff Harry Briggs Jr.

Biden's nod to history

Biden was 11 at the time of the of the landmark decision, which involved plaintiffs from Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, Washington, D.C. and his home state of Delaware.

As a senator in the 1970s, he would oppose the forced integration of schools through a process known as busing, which saw Black students brought into white communities for classes in an attempt to increase racial diversity — and even led an effort in the Senate to quash the program.

His stance on the policy became a flashpoint in a 2019 presidential debate when he was competing for the Democratic nomination. He came under fire from none other than his future running mate Kamala Harris, who told him she was bused to school as a child.

The Black community would later give him his first victory in South Carolina, which prompted Biden's campaign comeback. Civil rights leader and Democratic Congressman Jim Clyburn's endorsement played a major role. Biden then picked Harris to join his ticket. When they were elected, she became the highest-ranking Black woman to ever hold higher office.

He again made history when he put Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson on the Supreme Court.

Henderson called Harris' election and Jackson's appointment "extremely consequential events." She hopes to one day meet the first Black woman to serve on the high court. "This particular team of president and vice president like no other have a direct connection to Brown," Henderson said.

Henderson's last visit to the White House, when Obama was in office, was equally if not more pivotal. She recalled that it "just brought everybody to their knees and some tears" when the nation's first Black president arrived.

"He looked around the room and just said, look at where we are now," she recalled. "And everybody in the room knew what he meant."

Cause for celebration

Henderson was just three years old when Brown was decided. She and the other children whose parents were plaintiffs have largely relied on research and the memories of their elders to narrate the case.

She began a foundation in 1988 to keep it in the public discourse and educate the public on its affirmation of the 14th amendment.

"One of the reasons for starting the foundation was to help our state and our city of Topeka embrace this history and recognize that it wasn't a negative, that it was in fact something positive that we had done for the nation," she said.

Henderson said her mother, Leola Brown Montgomery, was pregnant with her when the NAACP approached the family about joining the suit. Her late father, Oliver Brown, was was studying to an African Methodist Episcopal pastor and working as a welder fulltime. Henderson said her mother convinced him, as someone who looking to become a leader in the church, to sign on to the litigation.

He became plaintiff 10 of 13 families that ultimately made up the group.

Workplaces, neighborhoods and some churches were already integrated in Kansas at the time, she explained. It was only elementary schools in cities that had 15,000 people or more in Kansas that were segregated. Henderson's sister Linda was one of the Black children who was turned away from an all-white school.

When the Supreme Court decision came down, Topeka was one of the public school systems that immediately complied. Henderson said she began school the following year in 1955.

The situation was not as rosy in South Carolina, said Briggs. His family was named in the South Carolina case Briggs v. Elliott that was combined with the Brown case.

It took ten years for the community he lived in to integrate the school system, he said.

"It was a struggle in South Carolina," he told reporters Thursday. "It's nice to celebrate and commemorate, but I know the struggle still continues in some of the school districts around this country. I know that unequal access to education still exists in this country. "

More: Supreme Court allows Louisiana's congressional map with new, mostly Black district

Now a resident of Florida, Henderson still goes back to Kansas on the anniversary for commemorative events. She'll be returning on Friday, she said, after Biden's museum speech.

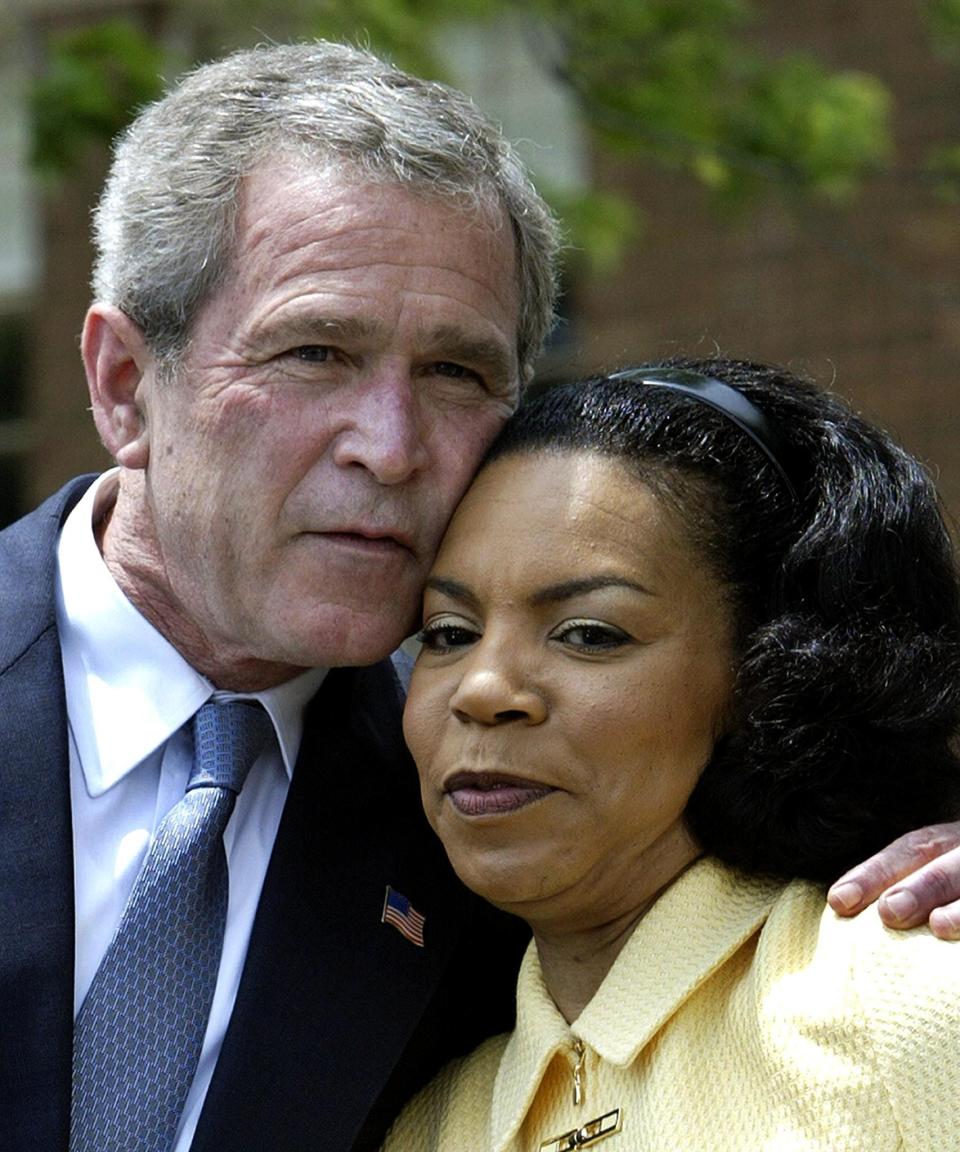

Henderson said the event with Biden at the White House for litigants came together after she told organizers of the broader events that previous administrations, including former Republican President George W. Bush's had hosted the group on major anniversaries. Thursday was her eighth time at the White House.

"We know we have a lot of work to do, in that education is still challenging in some places. But we have to realize that education is foundational to our country, and the more we can make certain our children are accomplishing and contributing, the better things will be," she said during the news conference.

The meeting was private, but Biden acknowledged the anniversary in a proclamation. While the ruling "allowed so many schools to develop diverse, inclusive learning communities that value empathy, kindness, and tolerance, the full potential of Brown v. Board of Education remains unfulfilled."

"There is still so much work to do to ensure that every student has equal access to a quality education and that our school systems fully benefit from the diversity and talent of our students ? because diversity has always been one of our Nation's greatest strengths," Biden wrote.In addition to the Oval Office meeting, Biden will deliver remarks on Friday at the African-American History Museum in Washington, D.C. and hold a closed-door meeting with the leaders of the Black fraternities and sororities that make up the Divine Nine. Biden is also giving the commencement address on Sunday morning at Morehouse College, a private school for Black men in Atlanta, and delivering the keynote address at a NAACP dinner that evening in Detroit.

Harris was on a trip Milwaukee on Thursday and was not present for the Oval Office meeting, but she'll take part in the Divine Nine meeting on Friday.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Milestone anniversary: Biden meets Brown v. Board of Education families