We May Have Found a Target For Treating The Fatigue of Long COVID

Researchers have just discovered a process in fruit flies which links inflammation with impaired motor function, providing researchers with a potential target for treating the persistent muscle fatigue that follows many infections.

Of long COVID's numerous symptoms, an intolerance to exertion could be considered one of the more debilitating.

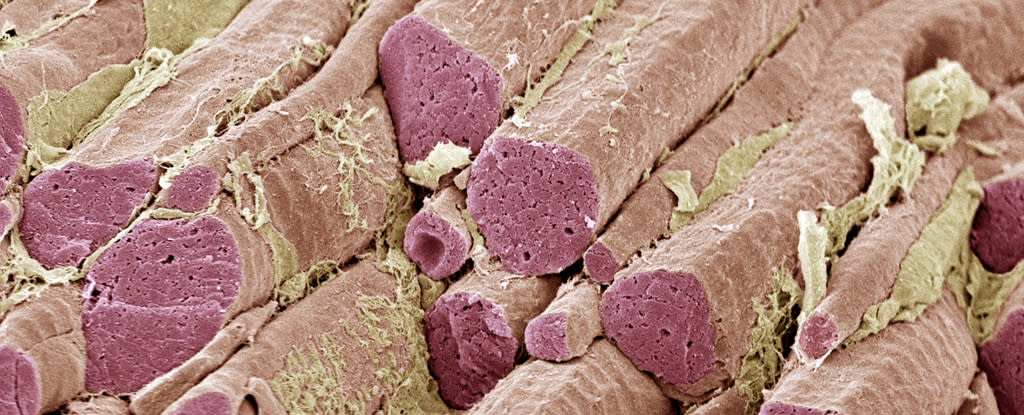

"This is more than a lack of motivation to move because we don't feel well," says Washington University developmental biologist Aaron Johnson. "These processes reduce energy levels in skeletal muscle, decreasing the capacity to move and function normally."

With every new infection of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, our risk of experiencing long COVID increases. Almost 18 million adult Americans have now faced this lingering malaise and its exhausting physical symptoms.

Many of these symptoms are familiar, including the frustrating loss of energy that hits around half of all long COVID sufferers. Muscle fatigue is also present in other post-viral conditions, as well as in people suffering from neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's.

The thing all these conditions have in common is inflammation of our central nervous system. Chemical markers associated with brain injuries have also been identified in COVID patients.

So Washington University developmental biologist Shuo Yang and colleagues used animal models to explore how inflamed neurons can lead to malfunctioning muscles. They identified a signaling pathway between the brain cells and muscles in both flies and mice that leads that leads to a loss of muscle function.

"Flies and mice that had COVID-associated proteins in the brain showed reduced motor function – the flies didn't climb as well as they should have, and the mice didn't run as well or as much as control mice," explains Johnson.

"We saw similar effects on muscle function when the brain was exposed to bacterial-associated proteins and the Alzheimer's protein amyloid beta. We also see evidence that this effect can become chronic. Even if an infection is cleared quickly, the reduced muscle performance remains many days longer in our experiments."

In humans, inflammation causes neurons to release the immune cytokine interleukin-6 (IL-6). The team found a comparable protein in their test animals traveled to their muscles via the bloodstream and activated a cellular program called JAK-STAT. JAK-STAT then turned down the amount of energy produced by the muscle tissues' mitochondria power plants.

"We're not sure why the brain produces a protein signal that is so damaging to muscle function across so many different disease categories," says Johnson.

"If we want to speculate about possible reasons this process has stayed with us over the course of human evolution, despite the damage it does, it could be a way for the brain to reallocate resources to itself as it fights off disease. We need more research to better understand this process and its consequences throughout the body.

Yang and team then used drugs to block this pathway in flies to confirm the process can be reversed, as has been shown in previous mouse studies. IL-6 inhibitors have already successfully been used to treat autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, and have shown promise in a few severe COVID-19 cases so far.

"It seems likely that the brain-muscle axis is activated by respiratory infections via the CSF [cerebrospinal fluid]… and continues to signal long after the initial infection is cleared," the researchers write in their paper. "Long-COVID may therefore be caused by chronic cytokine signaling."

Some parts of this puzzle remain unclear, the researchers caution, like how SARS-CoV-2 gets into the central nervous system in humans to trigger this inflammation. But this new information could lead to some much needed relief for those suffering from a range of chronic conditions.

By altering chemicals secreted by our neurons, it is now clear how brain inflammation caused by many different conditions can have such a profound physical impact on our entire bodies.

This research is published in Science Immunology.