A man of many firsts, Joseph Hatchett finally gets his day in courthouse naming ceremony

Jim Crow laws prevented FAMU Law graduate Joseph Hatchett from taking lunch or staying overnight in the hotel where the two-day Florida Bar exam was administered in 1959.

Hatchett passed the exam, was admitted to the Bar and went on to become a man of many firsts – and now he has a courthouse named after him.

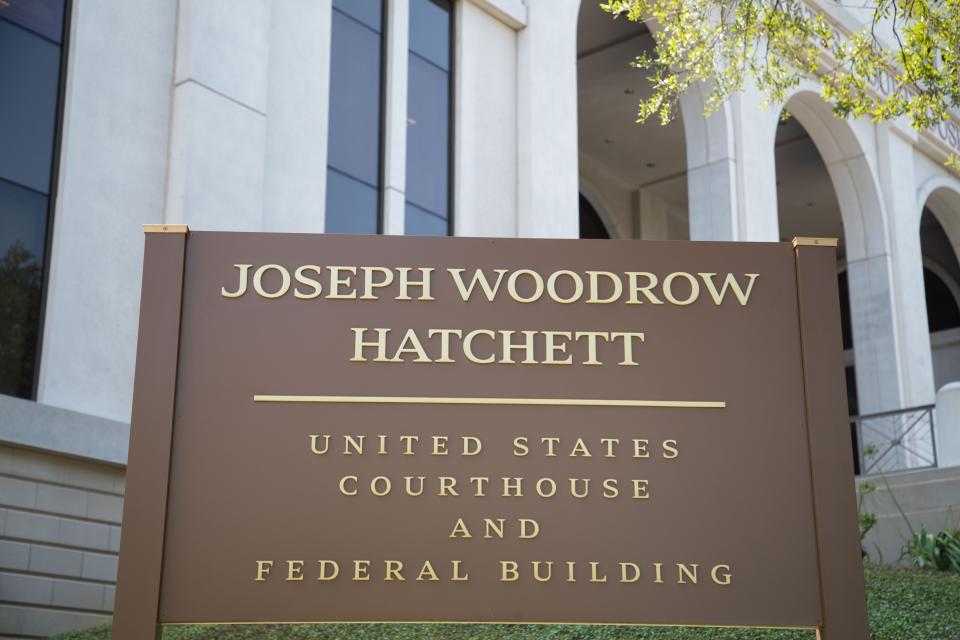

A ceremony Friday officially renamed the federal courthouse in Tallahassee the Joseph Woodrow Hatchett U.S. Courthouse and Federal Building in honor of the trailblazing civil rights pioneer, lawyer and judge.

The two-hour dedication drew judges, lawyers, and clerks from across the South and Florida – more than 200 people joined Hatchett’s family for the event, they filled a courtroom and two overflow rooms.

A Daytona native and Florida A&M University graduate, Hatchett was remembered by former clerks and colleagues as a jurist who never lost faith in law as an instrument of justice.

Eleventh Circuit Judge Charles R. Wilson clerked for Hatchett in the 1970s and said the nearly 600 opinions Hatchett wrote reveal a deep compassion for protecting the rights of people, especially the oppressed.

“What distinguishes a Hatchett opinion is that it is clear and concise. No Latin. They were written so that they can be read and understood even if you were not a lawyer,” said Wilson.

Hatchett passed away in 2021 at the age of 88.

The designation of the courthouse in his honor quickly became embroiled in Congressional partisan politics, which delayed Friday’s recognition by more than six months.

House Republicans organized to block passage after they uncovered a Hatchett opinion that upheld a Florida court ruling that prohibited student led prayer at public-school events.

That rift was a sidenote to Friday’s ceremony.

Partisan maneuvering

Congressman Neal Dunn, R-Panama City, who voted initially to block the designation over a procedural question, was a featured speaker.

Then-Congressman Al Lawson, D-Tallahassee, who used a parliamentary maneuver to revive the measure, which passed, was a spectator in the audience.

Dunn, who supported the Lawson initiative, recognized and thanked Lawson for his effort in his remarks.

Coincidently, Hatchett had headed a three-judge panel in 1992 that created three Black-access congressional districts, one which Lawson held 2016 – 2022.

Painting the town red: How Ron DeSantis is trying to turn Tallahassee Republican

Recent headlines: Florida groups challenging DeSantis congressional map hail 2nd favorable high court ruling

Gov. Ron DeSantis and Republicans in the Florida Legislature erased those districts when they redrew the congressional map for the 2022 election. That redesign is currently under challenge in federal and state courts.

Jim Crow and a man of many firsts

Hatchett was the first Black justice to serve on the Florida Supreme Court, when former Gov. Reubin Askew selected him to replace Justice David McCain who resigned amid corruption charges.

The next year when he stood for reelection, he became the first Black man since Reconstruction to win a statewide election in the South, and remains the only Floridian to do so.

Dunn said those accomplishments are inspiring because they came at the height of the Civil Rights era and that Hatchett faced the kind of obstacles that many in the audience have never experienced.

“He knew that to make change you have to roll up your sleeves and do it. This is something I think sometimes Americans have lost today,” said Dunn.

In 1979, President Jimmy Carter appointed Hatchett to the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals – the first Black jurist to sit on an Appeals Court in the former Confederacy.

Hatchett retired from the bench in 1999 and went into private practice in Tallahassee.

No fears, no regrets

His grandson, Roscoe A. Green, recalled summer days growing up talking to his grandfather about life.

“He said, ‘Roscoe, what would you do if you weren't scared? Do it. Otherwise, you’ll spend the rest of your life wondering what if?’ And if you look at his career, that's how he lived. He was not afraid to put himself out there. You do not get a courthouse named after you, without putting yourself out there,” said Green.

By putting himself out there Hatchett ultimately took the sting out of what may have been the defining statement of his 1976 Supreme Court campaign victory.

In 1976, Miami Circuit Judge Harvie S. DuVal, challenged Hatchett at a time when justices were elected, as opposed to today when they are appointed and then face a retention vote.

At a Panama City debate, DuVal reportedly introduced himself as someone whose name adorns landmarks, streets, and even a county from Tallahassee to Key West.

Known for his civility, when Hatchett spoke he did not correct DuVal or tell the audience his opponent was not that Duvall. Instead, he deadpanned, "My family has been in Florida for 150 years and nothing is named for them."

Hatchett won the election, with 63% of the vote.

“I wonder if Judge Hatchett could have imagined that almost 50 years later, the United States Courthouse in Tallahassee, Florida’s Capitol, just blocks from his alma mater, would be named the Joseph Woodrow Hatchett U.S. Courthouse and Federal Building,” said Wilson recalling the episode and eliciting applause.

Eleventh Circuit Chief Judge William H. Pryor Jr., presented the family a framed artist’s depiction of the name Joseph Woodrow Hatchett emblazoned on the Courthouse’s limestone fa?ade.

The signage has been ordered and will be installed at a later date.

James Call is a member of the USA TODAY NETWORK-Florida Capital Bureau. He can be reached at [email protected]. Follow on him Twitter: @CallTallahassee

This article originally appeared on Tallahassee Democrat: Tallahassee federal courthouse named for Judge Joseph Woodrow Hatchett