Know their names: A roll call of civil rights leaders who helped shape Tallahassee

Many strong locals advocated and fought for racial equality in Tallahassee, Florida’s capital city, and a battle ground in the national civil rights movement.

From nurses to shop owners, NAACP chapter presidents to students, those who had a stake in their community stood up to racial inequality.

Congress passed the federal Civil Rights Act in 1964, prohibiting discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex and national origin.

Even still, steps taken at the national level would rely on the longtime work of local activists to affect change. Tallahassee was home to many influential activists for racial equality.

'Freedom is never given freely': Remembering when Martin Luther King came to Tallahassee

More: A virtual tour through the African American History of Tallahassee

What follows are snapshots of some of the activists engaged in changing the landscape of racial equality in Leon County.

Insights provided by local historians Althemese Barnes and Delaitre Hollinger made this article possible. Aron Myers, the current director of the John G. Riley Museum, also contributed.

By no means a comprehensive list, here are some of those never-to-be-forgotten names.

FAMU alumni and Tallahassee activism

Robert and Trudie Perkins

Civil rights “power couple” and graduates of FAMU, Robert and Trudie Perkins advocated for racial equality in the Tallahassee community and beyond.

“They’re probably the most little known, under-recognized civil rights leaders in our city’s history,” Hollinger said. “But the most significant.”

Though the pair made many great strides toward equality, such as Robert Perkins’ calls for African American recreational spaces, one of their most notable achievements was their fight for equal pay for African American employees.

In 1971, Trudie Perkins, alongside a coworker, raised issues about unfair treatment at her workplace. She worked as a nurse at Tallahassee Memorial Hospital, and after complaining about their discriminatory employment practices, she was terminated in 1972.

In response, Robert Perkins helped workers file complaints with the US Department of Justice. Citing the discriminatory practices brought to their attention, the Department of Justice then issued a consent decree to the City, ordering that the racial makeup of their new hires would need to proportionally reflect the city’s demographics.

“(Perkins) made many sacrifices as did his wife to gain equal access for Blacks, filing lawsuits on behalf of discriminatory policies and practices,” Barnes said.

Florida A&M University recently renamed Gamble Street on the university’s campus as the “Robert and Trudie Perkins Boulevard.”

Wilhelmina Jakes and Carrie Patterson

In 1956, Jakes and Patterson, students at FAMU, were arrested for refusing to forfeit their seats near a white passenger on the public bus. The two women were publicly harassed, and they were threatened with a burning cross placed in their front yard.

More: 'History is knowledge' as Tallahassee bus boycott marks 64 years

This act of racial injustice served as inspiration for then-Tallahassee NAACP president Robert Saunders, alongside the Rev. C.K. Steele, to begin a city-wide bus boycott in a move to desegregate public transportation.

“They were the initiators of the Tallahassee Bus Boycott,” Hollinger said.

Patricia Stephens Due and Priscilla Stephens Kruize

As FAMU students in 1960, sisters Stephens Due and Stephens Kruize founded the Tallahassee chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality. The duo led a series of sit-in protests at segregated lunch counters around the city; they were eventually arrested alongside a group of other students. Refusing to pay the fine, the sisters and students held a “jail-in” and spent 49 days in jail, attracting national news coverage.

“(They) were responsible for bringing attention to the ugliness that existed in the late ‘50s (and) early ‘60s with...segregation taking place,” Hollinger said. “There were Black students all over the country who were sitting in lunch counters after the Stephens sisters.”

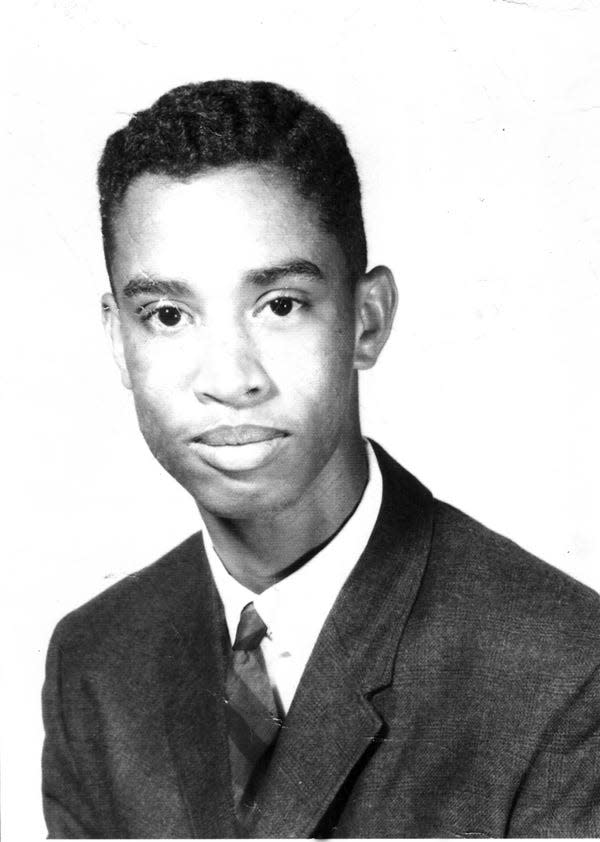

George Calvin Bess, Jr.

A student at FAMU, Bess worked as a voting rights activist with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

“He traveled throughout the south, registering voters and bringing attention to the racial discrimination and segregation that was going on during that time,” Hollinger said.

In 1967, Bess, a Tallahassee native, “died under suspicious circumstances” while registering Black voters in Mississippi, according to the Florida Memory Project.

Lessie Graham Sanford

Sanford was a FAMU alumna and a career school teacher in Leon County who also played an influential role in the local civil rights movement.

“She was what one would call a quiet-spirited soldier,” Barnes said. “Lessie did not talk a lot, but made sure that the marchers were accommodated hospitality-wise.”

According to Barnes, Sanford worked as a freedom driver, voter registrant, refreshment preparer and server.

Local NAACP and government

Rev. Daniel Speed

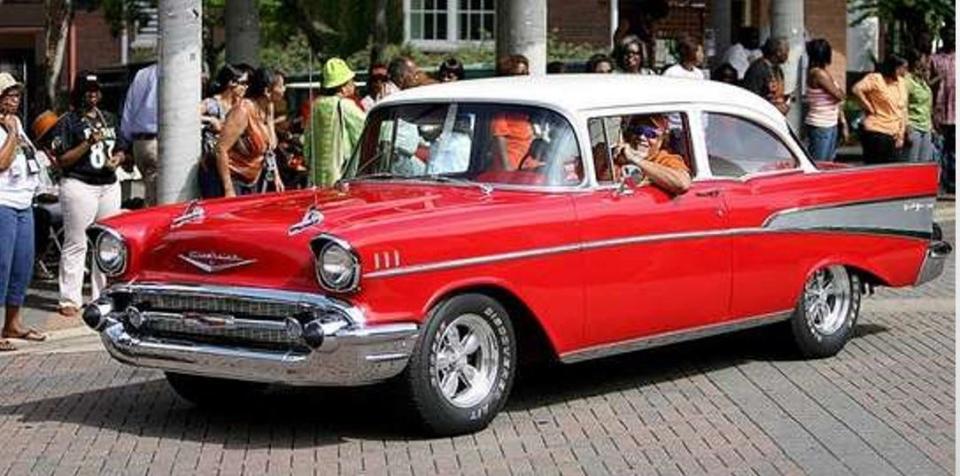

During the Tallahassee Bus Boycott in 1956, Speed, alongside Rev. C.K. Steele, operated a carpool service to provide transportation for African-Americans.

Both men were arrested for operating the service without a license. Despite pushback from police and city officials, the bus boycott successfully created a financial strain on the city and led to the desegregation of Tallahassee public transportation.

Speed was the second president of the Tallahassee NAACP, serving as Steele’s replacement for four years.

Barnes remembers the work of Rev. Speed.

“He was a regular at Civil Rights Mass Meetings, which I attended,” Barnes said. “It was also known that a key meeting place for Civil Rights business meetings was his Speed Grocery Store on Floral Street in Bond Subdivision.”

Reverend C.K. Steele

According to Hollinger, Steele was involved in a lawsuit against the Leon County school district for the integration of public schools. He protested against the segregation of lunch counters, department stores and the Tallahassee airport. Steele also led the Tallahassee Bus Boycott and marched in the Selma to Montgomery marches of 1965 to demand voting rights for African Americans.

More: C.K. Steele roadway designation unveiled as 'gateway' to Tallahassee

More: Martin Luther King Jr., C.K. Steele honored in Tallahassee

More: 'A perpetual source of light': Beloved Tallahassee musician Darryl Steele dies at 6

Barnes called Steele a leader in the civil rights movement.

“Rev. Steele was quite involved in the civil rights movement on a national level as the founder of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. served as president of,” Hollinger added.

In 1951, Steele became the first president of the Tallahassee NAACP, serving for 15 years.

“I still recall vividly his fight to rename Boulevard Street to MLK Boulevard,” Barnes said.

According to Barnes, Steele had bone cancer at the time and had to be physically assisted to stand and speak at the Leon County Courthouse.

“Despite the illness, his voice was as strong and on point as ever,” Barnes said.

Father David Brooks

Brooks came to Tallahassee in 1947, when he began serving as vicar of St. Michael and All Angels Episcopal Church, a site of many Youth NAACP and civil rights meetings, and Episcopal Chaplain at FAMU. His influence extended throughout the Tallahassee community, and he was actively involved in the city’s civil rights movement as a member of the Inter-Civil Council and president of the NAACP.

“He was among the group of leaders that advocated successfully for Blacks to be placed on the Tallahassee Police Force resulting in the first three hires: Fred Lee Sr., Clarence Mitchell and Jack Golden,” Barnes said.

More: St. Michael and All Angels marks 135 years of ministry

More: Celebrating the leadership of Black churches in Leon County

Anita Davis

A Tallahassee resident since leaving New York in 1979, Davis became the first Black woman to be elected to the Leon County Commission in 1990. She served on the Commission for six years, chairing it for two of them, after which she left her position to run for Congress.

Davis was president of the Tallahassee NAACP for a total of 12 years. Her work with both the NAACP and the Commission improved the quality of life for thousands of Tallahassee’s Black residents and other underrepresented populations. She was instrumental in helping bring parks, a library and a health clinic to Tallahassee’s southside.

More: Anita Davis, first Black woman elected to Leon County Commission, dies

Barnes served in Davis’ cabinet on Education and ACT-SO Youth Committees and assisted Davis with fundraising the money needed to file for single-member districts in Leon County.

According to Hollinger, Davis sued Leon County, accusing the county of violating the Voting Rights Act of 1965 because all of the five county commission seats were elected at large.

“This prevented for many years African Americans from being elected to the county commission,” Hollinger said. “But through Davis’s lawsuit, the courts ruled in her favor.”

In 1986, the Leon County Commission moved to five single-member district seats, adding two additional at-large seats and allowing each of the county’s electoral districts to elect their own representative. That year, the first Black county commissioner, Henry Lewis III, was elected.

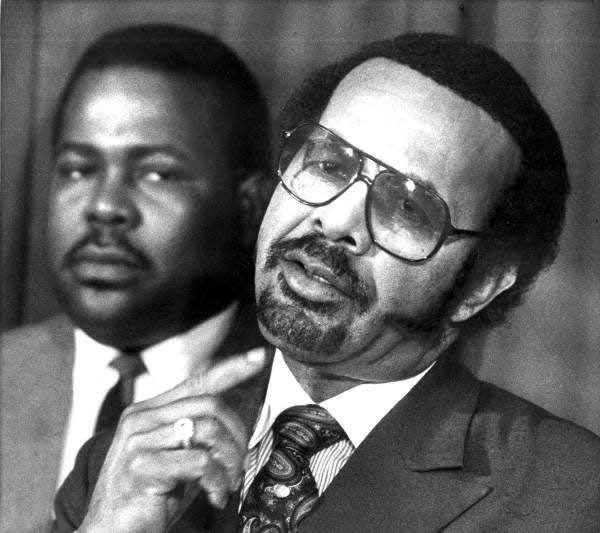

Charles Evans

During his lifetime, Evans served as president of the Tallahassee branch of the NAACP and worked as a Professor of Marketing in the School of Business & Industry at FAMU for over 30 years. Evans was one of the first African-Americans to move into the Myers Park neighborhood. His activism began in high school when as a senior he attended the first March on Washington in 1963. He later attended the 25th Anniversary March with his family.

? Read Charles Evans' obituary

According to Hollinger, Evans advocated for the appointment of the first Black assistant fire chiefs and the first Black police chief. He was also instrumental in the City of Tallahassee hiring its first Black city manager and in issues of historic preservation, and he was responsible for the Tallahassee NAACP acquiring a permanent office building.

Hollinger said Evans played a key role in eliminating the practice of redlining in Tallahassee communities.

Redlining is a common term used to refer to a bank’s refusal to approve someone for a loan because they live in an impoverished area and are deemed a financial risk. Historically, redlining practices have divided areas by racial demographics.

“He brought the bankers together and was able to bring attention to the redlining that was going on,” Hollinger said.

More: Late activist Charles Evans' daughter brings his legacy to south-side redevelopment

Hollinger said Evans was vocal about issues with police conduct, and advocated for an independent police review board many years before one was created.

During Evans’ tenure as the president of Tallahassee’s NAACP, Barnes served as a member of his cabinet and witnessed his work on the advancement of equal minority employment for Black citizens in public sectors.

Community advocates

Rev. R.N. Gooden

In the 1970s, Tallahassee resident Gooden advocated for the appointment of Black judges to state circuit courts and to the Supreme Court, Hollinger said. Gooden marched for prisoners on death row. He advocated for the construction of low-income housing, and he boycotted stores for selling contaminated products to poor people.

“Rev. Gooden, from the very beginning, was very active and vocal in ensuring that African Americans and any person, no matter their color, was treated with dignity and respect,” Hollinger said.

According to Hollinger, Rev. Gooden marched for voting rights alongside Steele. In one 1971 incident, voter registration books were being kept inside a private business as opposed to the public courthouse, and Steele and Gooden were key players in the civil rights march that urged for the books to be moved.

Hollinger also noted that Gooden brought attention to the many discriminatory practices occurring during the hiring, promoting, and disciplinary processes within some of Tallahassee’s prominent organizations, including local hospitals, school districts and the police force.

“He was very vocal and forceful in ensuring that each of those entities hired African Americans in high-ranking positions,” Hollinger said. “He was relentless.”

Dr. Robert Hayling

Hayling was a graduate of FAMU, later earning a Doctorate of Dental Surgery from Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tenn. Hayling’s first involvement in the civil rights movement began during his time at Meharry, where he engaged in sit-ins and protests.

Hayling later opened a dental practice in St. Augustine, where he also became the head of the city’s NAACP Youth Council and played a key role in bringing Martin Luther King Jr. and King’s supporters to the city, organizing civil rights protests that attracted national media attention.

? Read more about Dr. Robert B. Hayling

After moving to Fort Lauderdale in 1966, Hayling became the first Black dentist in Florida to be elected to the local, regional and national levels of the American Dental Association.

“He is sometimes credited as being the father of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 with the tremendous desegregation campaigns that took place in St. Augustine under his leadership,” Hollinger said.

Edwina Gibbons Stephens

Known to many as a pioneer of change and environmentalist in the Tallahassee health care industry, Gibbons Stephens exerted her influence at FAMU and Tallahassee Memorial Hospital. She was the first African-American Surgical Nursing Supervisor at TMH, and she often fought against inequalities in underserved communities.

More: Golf tournament held in honor of the late Edwina Stephens, Jake Gaither

More: Congressman wants to name post office for Edwina Stephens, 'mother of Southside'

Gibbons Stephens facilitated the hiring of Black cashiers at local Winn-Dixie stores and helped lead a successful movement to shut down a medical waste facility in Tallahassee’s southside, among other accomplishments. In April, U.S. Congressman Al Lawson introduced a bill to rename a Tallahassee post office in her honor.

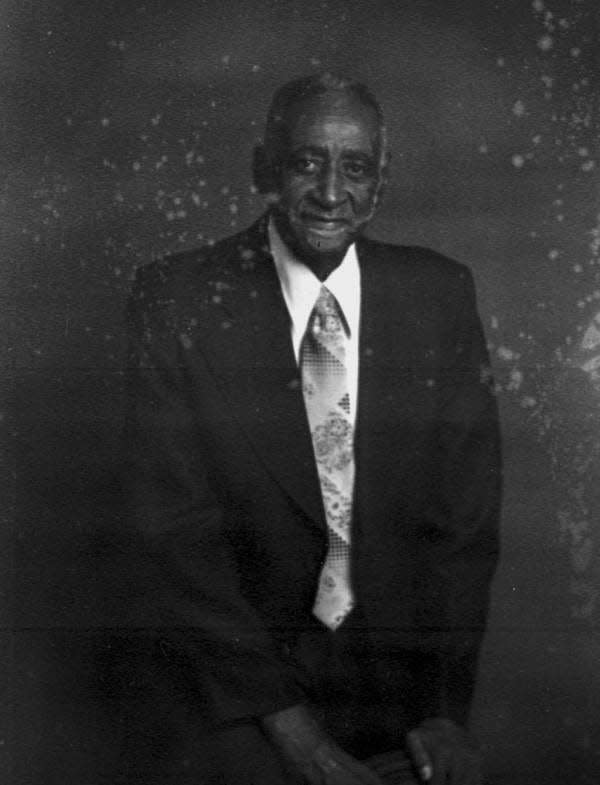

Rev. King Solomon Dupont

In 1957, Rev. Dupont was Tallahassee’s first Black political candidate to run for office since Reconstruction when he ran for a spot on the city commission. He was one of the founding members of the Inter-Civic Council, and he helped operate alternative transportation during the Tallahassee Bus Boycott. He lost his 1957 political bid.

Rev. Dupont served as pastor of Fountain Chapel African Methodist Episcopal church in the 1950s. Barnes said Dupont was “very active as a leader, along with Rev. Steele and other ministers,” adding that his run for the city commission back then was “a rarity.”

More: Dupont was Tallahassee's first Black candidate in 1957

Who did we miss?

Email us at [email protected]. Please include their name, tell us about their service to the cause and include a photo if possible. We'll publish the best suggestions in a future edition of the Democrat during during the month of February, Black History Month.

City honors agents of change with historical markers

In leading up to today’s parade downtown and planned activities this afternoon, city officials have honored King and local civil rights leaders who were agents of change here at home.

On Thursday, the city unveiled “Dream Builders—Voices of the Movement,” three historic markers in honor of the local Civil Rights Movement and its national impact:

Marker 1: (located near Florida A&M University, just south of FAMU Way) This marker honors Martin Luther King Jr. and his broader work for civil rights throughout the United States, as well as the activism of local civil rights leaders who lobbied the City Commission to rename Boulevard Street, stretching from Palmetto Street to North Monroe Street, to Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard. This marker also honors community and civil rights activists Father David Henry Brooks, Reverend King Solomon Dupont and Edwina D. Stephens.

Marker 2: (located at 524 North Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd., Frenchtown Heritage Hub) This marker highlights Reverend Charles Kenzie (C.K.) Steele, his relationship with Dr. King, his involvement with leading Bethel Missionary Baptist Church in the civil rights movement and efforts for the Tallahassee bus boycott. The marker also honors those who served as “foot soldiers,” providing logistical support for the movement, including Lessie Graham Sanford and Cornelia Roberts Osborne.

Marker 3: (located on the corner of Seventh Ave. and Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd.) This marker honors the history of the Levy Park neighborhood, desegregation in Leon County Schools and the work of early pioneers, including Elaine Thorpe, Philip Hadley, Marilyn Holifield, Melodee Thompson and Harold Knowles, in their respective roles of integrating the local school system. The marker also honors Dr. King’s advocacy for education.

On Saturday, the late Tallahassee Branch NAACP President Charles Evans was honored during a dedication ceremony for the Dr. Charles L. Evans Pond Park, 816 Circle Drive.

Faith Matson, a recent FSU graduate and former FSView writer, participates in the Florida Student News Watch, a grant program for student writers funded by the Florida Society of Professional Journalists. This story was edited by CD Davidson-Hiers. Email [email protected] for more information.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story had an incorrect photo for George Calvin Bess.

Never miss a story: Subscribe to the Tallahassee Democrat using the link at the top of the page.

This article originally appeared on Tallahassee Democrat: Know the name: Local civil rights leaders who helped shape Tallahassee