We know more about the surface of Mars than about the floor of Lake Michigan. But what we do know is remarkable.

Lake Michigan wasn’t always a lake. At least not the lake we know today.

Thousands of years, and remnants of past lives, all lie under its surface, from ancient shorelines to a submerged forest, and from ships that plied the water to aircraft that flew over it.

And that's just what we know. Much of Lake Michigan, as well as its four siblings, remains a mystery.

Only 15% of the bottom of the Great Lakes has been mapped in high resolution. Scientists have said they know more about the surface of Mars than they do about the bottom of the largest fresh surface water system on earth.

Here are some that have been discovered so far.

Previous shoreline reveals early lake, forest

The lakebed had many lives before it filled in with rocks and sand.

During the last Ice Age, an ice sheet up to two miles thick covered most of Canada and the northern United States, accounting for millions of square miles. As the climate warmed roughly 20,000 years ago, the ice — known as the Laurentide ice sheet — began its northward retreat, creating ancient Lake Algonquin about 12,000 years ago.

The lake, which can be considered Lake Michigan’s grandmother, covered parts of what are now Lakes Michigan, Huron and Superior. The ancient lake stood more than 25 feet higher than where present-day Lakes Michigan and Huron sit today.

As the region became much more arid and water levels dropped, only the deepest parts of Lake Algonquin remained filled. One of those became Lake Chippewa, or Lake Michigan’s mother, about 10,000 years ago.

The Great Lakes didn’t become what they are today until 6,000 years ago – fairly recent geologically speaking.

The outline of Lake Chippewa’s basin, smaller than Lake Michigan, is still visible on the present-day lake's bottom.

What’s hiding along the ancient shorelines “is really an open question," said Ashley Lemke, an underwater archaeologist at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

Lemke has been doing underwater research in Lake Huron for a decade, but is ramping up projects in Lake Michigan. She said it’s possible there are fossils of mastodons and mammoths as well as stone tools from prehistoric people.

Lake Chippewa isn’t the only water feature now submerged beneath the lake. There is a silhouette of a now submerged delta on the lake floor just east of Washington Island in Door County.

Heading south, the remains of an underwater forest was discovered by salvage operators about 15 miles southeast of the Chicago Harbor Lighthouse in 1989. Scientists later confirmed there are at least 50 stumps of oak and ash trees – some containing branches – across 3,200 square miles. The preserved, rooted stumps are more than 8,000 years old.

And on the other side of the lake, an underwater archeologist discovered an unusual rock structure in 2007 at the bottom of Grand Traverse Bay in Michigan. It's been dubbed the Lake Michigan Stonehenge. But Lemke cautioned that it hasn’t been confirmed that humans put it there.

More: Wisconsin’s national marine sanctuary is a museum beneath the water. Here’s what to know.

Lakebed has diverse terrain, just like on land

The Ice Age left behind diverse physical features, and maps of the lake floor reveal contours just like on land, with plateaus, ridges and valleys.

While topographic maps – the ones that hikers use – show how high landforms are above sea level, bathymetric maps show how deep landforms go below sea level.

The deepest part of the lake is found in the South Chippewa Basin in the southern part of former lake. It was the heart of Lake Chippewa, and its estimated depth reaches 925 feet – more than 1.5 times taller than the U.S. Bank Center in downtown Milwaukee.

East of Milwaukee, in the middle of the lake, is the Mid-lake Reef Complex, a small mountain that plateaus up to around 130 feet deep, said John Janssen, professor emeritus at UW-Milwaukee School of Freshwater Sciences. The reef complex is an important spawning site for lake trout, he said.

The bottom of the lake even looks a lot different depending on whether it’s the Wisconsin or Michigan side.

Prevailing winds move from west to east, so after thousands of years the sand has slowly followed suit. In Wisconsin, the lakebed is a lot rockier overall than it is on the Michigan side, which is much sandier, Janssen said. This is why Michigan and Indiana are known for sand dunes.

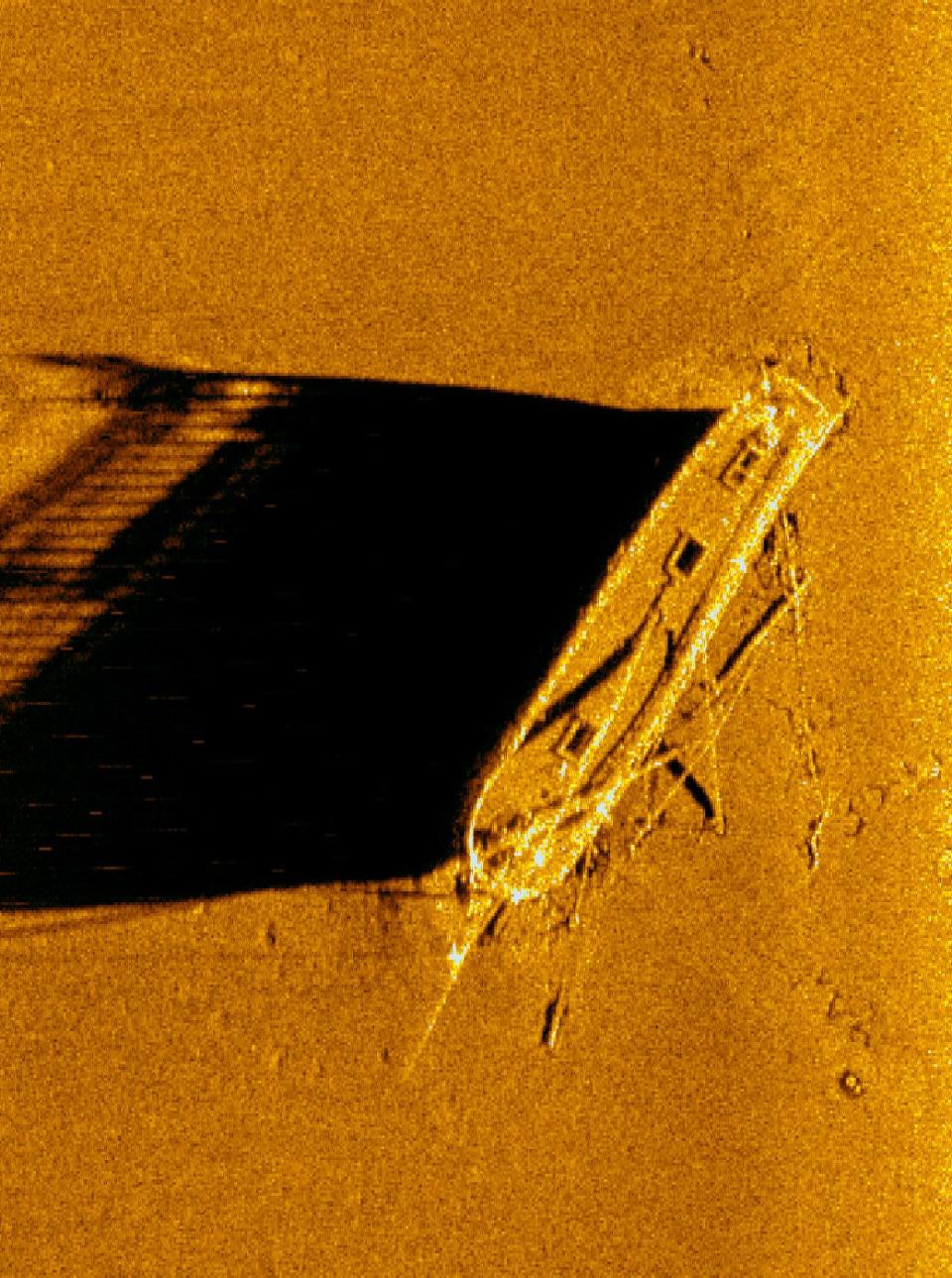

A graveyard of ships lost beneath the water

The Great Lakes is enticing if you're a shipwreck diver. The cold freshwater helps preserve wrecks and keep many details unspoiled.

“There's not many places in the world where you can see an intact wooden schooner preserved with its masts still standing,” said Becky Kagan Schott, a photographer who captures extreme underwater environments. “It’s like a Disney movie.”

Schott learned to scuba dive when she was 12-years-old, and one of her first dives was in Lake Erie. She has photographed underwater sites all over the world, but her favorite is the Great Lakes because so many shipwrecks are near-perfect.

It’s eerie, still and hauntingly beautiful down there, she said.

It is estimated more than 1,700 ships rest at the bottom of Lake Michigan, most of which have yet to be discovered.

About 780 shipwrecks sit submerged in Wisconsin’s Lake Michigan waters, but only 250 have been identified, according to Tamara Thomsen, maritime archaeologist at the Wisconsin Historical Society. The number jumped significantly in 2023, when a record-shattering 13 shipwrecks were discovered in Wisconsin’s Lake Michigan waters.

Across the lake, it’s estimated that there are about 635 shipwrecks and 230 have been located on the Michigan side, said Wayne Lusardi, state maritime archeologist at the Michigan Department of Natural Resources.

In Indiana’s Lake Michigan waters there are 14 known shipwrecks, most of which are cargo ships, according to the state’s natural resources department. It’s estimated that there are 300 shipwrecks in Illinois’ lake waters, and only about 90 have been located, according to the Chicago Maritime Museum.

Lake Michigan is still hiding its oldest wreck, the Griffon, which was loaded with furs to pay the ship master’s creditors when it disappeared in 1679. It was on its way to Lake Erie when it was likely overcome by a September storm. Its resting place is believed to be northeast of Rock Island off Door Peninsula.

The largest wreck in Lake Michigan was the 623-foot Carl D. Bradley, which now rests 12 miles southwest of Gull Island off Charlevoix County, Michigan. The freighter sank in 1958.

The deadliest wreck in Lake Michigan – and all of the Great Lakes – was the Lady Elgin, which sank in 1860 after it was rammed by the schooner Augusta less than 10 miles from shore during a gale. About 300 people lost their lives, including the captain. Most of those who died were from Milwaukee; the tragedy decimated the Irish community in the Third Ward.

Divers discovered the steamship in 1989 near Highwood, Illinois.

Seeing the details of these wrecks, like boots that were taken off in a hurry, is “a haunting reminder that these shipwrecks, they're not just metal or wood on the bottom of the lake, but people lost their lives on these ships,” Schott said.

Hundreds of aircraft, even a Russian satellite, remain underwater

Shipwrecks aren’t the only piece of history memorialized on the lake bottom.

Lake Michigan is also home to at least 411 aircraft wrecks, more than any of the Great Lakes, Lusardi said.

During World War II, the U.S. Navy needed to train pilots to take off and land from aircraft carriers. German U-boats patrolled the East Coast, so the Navy turned to the Great Lakes, in particular Lake Michigan.

Roughly 15,000 pilots were trained near Chicago during that time, which led to 130 planes winding up at the bottom of the lake. Most were salvaged and displayed across the country. Others never left the cold waters.

The oddest aircraft is likely a Russian Sputnik satellite off Manitowoc.

Sputnik 4 was launched in May 1960 on what was supposed to be a four-day mission. It encountered a problem, and orbited continually until September 1962, when it finally fell over Wisconsin. The main sections reportedly went into Lake Michigan, and have never been found.

A working waterfront leaves its history

The mere presence of the lake, and ability to transport commodities long distances, fueled the economic rise of the region. The waterfront was the first point of connection as people and commodities came in on ships.

Lake Michigan had piers that stuck out like porcupine needles all around, Thomsen said. To this day, old docks, piers and caissons are all submerged along the shoreline. Some even stretch as far out as 1,000 feet, she said.

Dean’s Pier in Kewaunee County is one of the most well-preserved and easiest ones to see, Thomsen said. The pier extends 720 feet from shore with more than 100 pilings that sit in seven to 15 feet of water. Some pilings even break the water's surface during years when the water is low.

During the height of Wisconsin’s lumber industry, piers would be a business and community center, often housing their own general store and lumber mill. Wooden schooners, or lumber hookers, would crowd the piers as items were loaded. At Reynolds’ Pier near Jacksonport, two lumber hooker wrecks lie next to the pier, as do the remains of two schooners.

Even shipwrecks reveal the history of commerce at the time. For instance, the Lakeland was carrying Nash, Kissel and Rollins automobiles when it sprang a leak and sank near Sturgeon Bay in Door County in 1924. Schott said that dozens of cars are still stacked inside and next to the wreck.

These historical features reveal information about the vibrant communities that lived along the lake, said Russ Green, superintendent of Wisconsin’s national marine sanctuary.

“We just have this little snapshot from the 1800s moving forward, so who knows what else is there,” Green said.

Ecology of lake vulnerable to invaders

For all its history, Lake Michigan's floor has undergone its fastest transition over the last 100 years because of invasive species.

A tiny shrimp-like organism known as a scud used to dominate the bottom of the lake, said Harvey Bootsma, a freshwater scientist at UW-Milwaukee.

Then alewives, sea lampreys, Eurasian watermilfoil and others all were introduced into the lake and made their mark. None has had the impact, however, of quagga mussels.

The mollusks first arrived in the Great Lakes in 1997 after ballast water was dumped into the water from cargo ships coming from the Baltic Sea.

Now they are the dominant organism at the bottom of Lake Michigan.

A person could walk across the bottom of the lake from Milwaukee to Muskegon, Michigan, and step on quagga mussels the entire time, Bootsma said.

Invasive zebra mussels, which hitchhiked into the lakes in 1989, are also found along the bottom of the lake. But zebra mussels can only attach to hard substrates. Quagga mussels spread across the soft sand, and fare better in colder waters. They filter water, sucking out plankton that native species rely on for food. With up to 10,000 mussels per square meter, quagga mussels have the potential to filter the entire lake in about 10 days, Bootsma said.

That makes Lake Michigan much clearer, and can mean spectacular underwater views.

But clearer doesn’t mean better.

The filter feeders have greatly affected the ecology of the lake, and in some spots, they are caked onto shipwrecks and other artifacts, obscuring the details that make the wrecks come alive, Schott said. They’ve even started to threaten the ancient underwater tree stumps in the southern part of the lake.

“It’s bittersweet,” Schott said.

A mystery waiting to be solved

Efforts to unveil more of what’s hiding at the bottom of all the Great Lakes have been ramping up for several years. The Great Lakes Observing System, or GLOS, is behind the Lakebed 2030 Initiative, an effort by scientists, government agencies and other organizations to map and explore the lake beds.

Earlier this year, two Michigan representatives proposed a bipartisan bill to authorize $200 million to map the bottoms of all five lakes. The Great Lakes Mapping Act is co-sponsored by 18 lawmakers who represent Michigan, Minnesota, Wisconsin, New York, Ohio and Illinois.

Bathymetric maps – the ones that show depth beneath the water – can only go so far, especially given much of the data they are based on is outdated. According to a 2021 report from the observing system, high-resolution maps of the bottom of the lakes could be mapped within eight years with proper funding.

That is what the Great Lakes Mapping Act is hoping to accomplish.

The Wisconsin Shipwreck Coast National Marine Sanctuary is an example of how that kind of investment could work. Designated in 2021, the sanctuary includes about 82 miles of Wisconsin coast off Ozaukee, Sheboygan, Manitowoc and Kewaunee counties, and then extends out from seven to 16 miles.

When it comes to the lakebed, the marine sanctuary is likely the best understood spot in Lake Michigan, Green said. It contains dozens of shipwrecks.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has started to map the bottom of the site using sonar, which is like “painting a picture using sound,” Green said. Complementing that, the sanctuary is employing new technology, like robots, to examine specific features such as shipwrecks and habitats.

The bottom of the lake is a mystery waiting to be solved, Green said.

Caitlin Looby is a Report for America corps member who writes about the environment and the Great Lakes. Reach her at [email protected] or follow her on X @caitlooby.

Please consider supporting journalism that informs our democracy with a tax-deductible gift to this reporting effort at jsonline.com/RFA or by check made out to The GroundTruth Project with subject line Report for America Milwaukee Journal Sentinel Campaign. Address: The GroundTruth Project, Lockbox Services, 9450 SW Gemini Dr, PMB 46837, Beaverton, Oregon 97008-7105.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: On Lake Michigan's hidden floor, shipwrecks are just the beginning