Journalists continue to be targets, metaphorical and real

In 2017, attacks on the news media started at the top, with President Trump routinely using the bully pulpit to call out unfavorable coverage of his administration as “fake news,” and mainstream news organizations as “the enemy of the American people.” The president’s verbal assaults on journalists concerned press freedom advocates — from the U.N.’s human rights chief, who warned the president’s words could lead to “incitement for others to attack journalists,” to David Frum, a senior editor at the Atlantic who wrote that Trump’s words “are a direct attack on … international journalists’ freedom and even safety.”

While American journalists have faced threats of assault and in some cases, actual assault, it is in other countries where local journalists have paid the ultimate price for their profession.

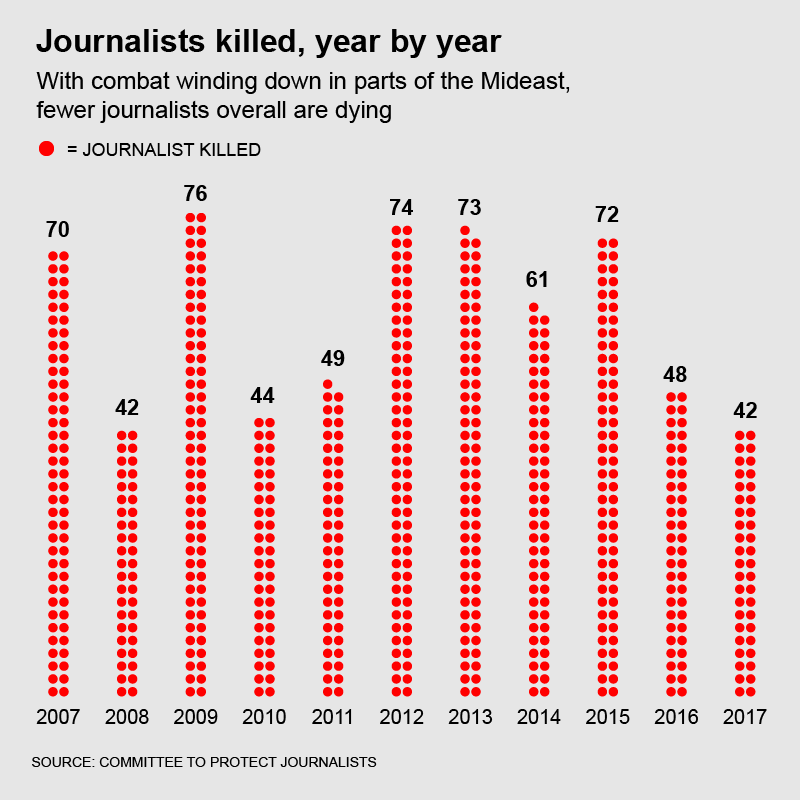

The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) found that in 2017, at least 42 journalists were killed as a result of their work (20 more killings are being investigated by the organization, but confirmed links to their work have yet to be found). Reporters Without Borders and the International News Safety Institute (INSI) respectively recorded 65 and 68 news media workers killed this year.

Those figures are down somewhat over the last two years. The simmering conflicts in Iraq and Syria continued to claim the most journalists’ lives, but the absence of fresh conflict in the Middle East may account for the decline.

Among the reporters who did lose their lives in war zones was 30-year-old Shifa Gardi, a locally well-known Kurdish television anchor. Gardi was reporting from Mosul, Iraq, when a roadside bomb exploded, killing her and injuring her crew. Described as “one of the most daring journalists” at the television station Rudaw, Gardi repeatedly returned to the frontlines to report on developments in the fight against the Islamic State. On one trip, she returned holding an injured rabbit, a casualty of war she was determined to rescue.

While fewer journalists lost their lives in active war zones in 2017, according to Robert Mahoney, deputy executive director of the Committee to Protect Journalists, targeted killings of journalists outside of combat did not abate.

“In countries where there’s no obvious conflict but where they are performing the great duty that journalists perform, which is to hold those in power to account, journalists are being killed,” said Mahoney. “Those journalists remain a focus. “

Daphne Caruana Galizia, once described by Politico as a “one-woman WikiLeaks,” epitomized to many the muckraking journalistic bulldog, assailing high officials for cronyism and everyday corruption in her extremely popular blog. At 53, she got her biggest scoop. Mining the Panama Papers — a trove of leaked documents that revealed where many of the world’s wealthiest and most powerful people “hide their cash” — Galizia wrote about purported links between Malta’s government officials and illicit shell companies. Officials denied the story, and Galizia faced libel suits and threats. Her dog was reportedly poisoned.

In October, as Galizia departed from her home, the car she was driving exploded. Her murder appears to have been brutally calculated, a bomb set off by a text sent by someone on a boat.

In an Oct. 17 Facebook post, her son, Matthew Caruana Galizia, who witnessed the aftermath of the car bombing, described “…running around the inferno in the field, trying to figure out a way to open the door, the horn of the car still blaring, screaming at two policemen who turned up with a single fire extinguisher to use it. They stared at me. ‘I’m sorry, there is nothing we can do,’ one of them said. I looked down and there were my mother’s body parts all around me. I realized they were right, it was hopeless.”

“Malta is an EU country, it’s not a country we’re used to seeing any journalists die in,” said Anna Bevan, assistant director for the INSI. “The way in which she was killed was so ghastly, and it really sent shock waves throughout the industry, and throughout Europe as well.”

Matthew Caruana Galizia has since blamed Malta’s leaders, and his family sued the police department for allegedly failing to conduct an impartial investigation into his mother’s death. Despite the arrest of several suspects who are now on trial for his mother’s death, Matthew posted on Facebook on Dec. 7, “Whatever those politicians with a lot to lose say, the status of justice for my mother’s murder remains the same: complete impunity.”

Shifa Gardi and Daphne Caruana Galizia joined an ignominious list of intrepid female journalists killed on the job in 2017. End-of-year surveys found that in 2017, women were killed at a rate more than twice the historical average.

“It’s a standout statistic for us,” says Bevan of INSI.

Fifty-five-year-old Gauri Lankesh was the most prominent journalist killed in India in recent years. In September, unknown assailants pulled up on a motorbike as Lankesh was returning from work, shot her in the head and chest, killing her on the spot. Lankesh ran a left-leaning, antiestablishment publication, which among other controversial stances, vocally criticized the Hindu caste system. In the last few years, Indian journalists deemed to be critical of Hindu nationalism have faced relentless online campaigns, including death threats. Female Indian journalists have also faced gender-based vitriol, and have been demeaned as “presstitutes” by social media trolls. Lankesh reportedly received a lot of hate mail before her murder. Outrage on university campuses over the independent journalist’s murder led government officials to assign a special investigative team to find Lankesh’s killers, who are still being sought.

Mexico set a record for targeted killings of journalists in 2017, according to CPJ. At least six journalists were killed in reprisal for their reporting. In several other cases, journalists were killed for motives that remain unclear.

Javiar Valdez Cárdenas covered corruption, crime and politics, and in Mexico all three beats intersect with the deadly drug trade. Exposing truths in his home state of Sinaloa meant regular threats to his life, but Valdez bravely persisted, writing prolifically in various publications and authoring several books on the narcotics underworld. In 2011, CPJ honored him with its International Press Freedom Award.

His last public remarks were made on a live television show. Among his comments, a bold accusation: “Politicians no longer have to go to the narcos to seek their backing,” Valdez remarked. “Nowadays, the narcos are the ones who create the politicians from the start.”

That same day, 50-year old Cárdenas was near the offices of Rio Doce, the investigative magazine he co-founded, when he was dragged out of his car by two hooded gunmen.

“The way in which they killed him was very symbolic. He was shot 12 times at 12 o’clock [near] the offices of the publication he ran, which means ‘12th river,’” says Bevan. “It was a standout case of a journalist killed as a direct result of his work.”

Based in Michoacán, a hotbed of cartel activity, Mexican journalist Dalia Martinez has seen many of her colleagues killed over the years.

In 2017, she lost a close friend, journalist Salvador Adame. A local television journalist, Adame was abducted by gunmen in Michoacán in May. His burned remains were found a month later.

“The last conversation we had was just three days before his assassination,” says Martinez. “He was the director of a television station, which did a lot of important coverage about corruption.”

The murders of Valdez, Adame, and another high-profile investigative reporter, Miroslava Breach, remain unsolved, their cases categorized as crimes with “complete impunity” under CPJ’s grim listing.

Mexico’s lack of protections for journalists, the possibility that local politicians and even police may be not only complacent but complicit, and a culture of impunity has made it increasingly dangerous for journalists like Martinez.

She says she’s received death threats to herself and her family by phone and in messages sent to her through WhatsApp.

“We all are fearful. Always,” she says.

And yet, Martinez is a professional. Journalism is her work, and she has no plans to leave it. “They can take some of us, but they won’t take others,” she says. “This is what we were born for. This is what we believe in, and we accept our destiny, even if it’s fatal.”

_____

Best of 2017 Yahoo News Features