Joe Biden Isn't the First President to Take Drastic Action to Avoid a Rail Strike

In September, the Biden administration brokered a deal between six of the largest freight rail companies and the leaders of the 12 largest rail workers’ unions to avoid a national rail strike. But almost immediately, the discontent among rank-and-file workers started bubbling up, and ultimately only 8 of the 12 unions ratified the contract. The other four voted it down, mainly because, despite a hefty wage increase and a single additional “personal day” for employees, the package did not include any guarantees for paid sick days. Now, heading into the holiday season, the freight rail system that is so essential to the proper functioning of the American economy could go offline. Beginning December 9, there could be a national rail strike that grinds the country to a halt.

In a move that smacked of no little desperation, President Biden hopped out this week to back congressional action in the form of legislation to force the workers to accept the September deal. The still-Democratic House passed the measure, although they also passed a resolution to provide workers seven paid sick days. The Senate passed the first measure, too, though they voted down the sick-days resolution. On paper, the strike threat is over. But the railroads don’t run on paper.

How did it come to this? According to a 2021 study from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 21% of American workers still do not have paid sick leave. The railroad companies are fighting sick leave because they’ve dramatically changed their business practices over the last six years to jack up profits. But how did workers so integral to the basic functioning of our economy not secure these protections long ago?

To find out, I called up Joseph McCartin, a labor historian at Georgetown University. In a conversation edited for length and clarity below, we discussed similar disputes from history and how Presidents Wilson and Eisenhower addressed them; the notion that paid sick leave demands are about dignity and respect as much as dollars and cents; and why the Biden administration’s missteps on this issue didn’t begin this week.

Throughout the last century, unions were first to secure many of the improved working conditions we now see everywhere. How do these workers still not have paid sick days?

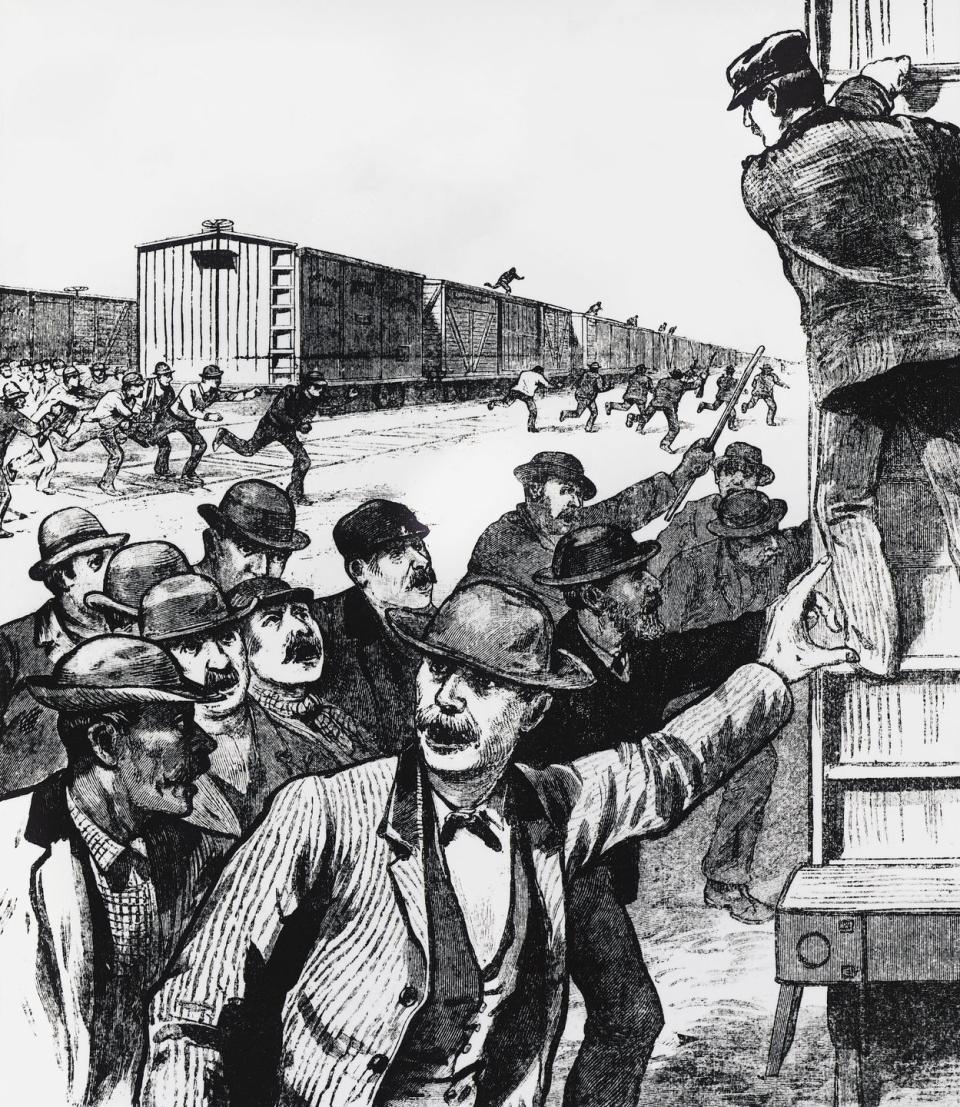

Railroads have always been a flashpoint in U.S. labor relations, and they have demanded federal involvement and the development of federal policy long before any other industry because they're so central and the economy depends so much on them. In the late 19th century, the federal government had to try to deal with labor relations problems on railroads. That led to early reforms in the early 20th century, and then to things like the Adamson Act in 1916. In a certain way, it's probably the most analogous situation to the one that we currently face, because on the eve of World War I, railroads were considering going on strike for the eight-hour workday. Wilson wanted to avert that, so he proposed a law that Congress passed that gave the eight-hour day to railroad workers before anybody else.

So railroads have forced the federal government to take policy positions in advance of other segments of the economy. It's not until the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938 that other workers start to get the eight-hour day. So you have an irony here, where the federal government has always been responsive to railroads, and yet we're now operating under a system of law that dates way back to 1926. It's an ancient law, it's in need of reform, and the current situation is driving to the surface, again, issues that broadly resonate.

Railroad workers are concerned about getting paid time off, getting a paid sick day. Coming out of this pandemic, when a lot of workers felt in a similar situation, I think one of the things driving the Great Resignation was a lot of people feeling that they did not have sufficient flexibility. They didn't want to return to jobs post-Covid that they felt so constrained in. So it's an irony that this area that produced some of the great breakthroughs in American labor relations has now fallen so far behind the curve. In part, that’s the dated nature of the legal apparatus that the workers are working under. In this case, management really played that apparatus to their advantage.

The reason why this is a crisis now for workers is that, over the past decade or so, the railroads have cut back about 30% in their personnel. It didn't mean they cut back rail shipments 30%—quite the reverse. So they're trying to take a shrinking crew of workers and run this highly sensitive coordinated system, and they don't have any margin—it puts it all on the workers’ shoulders. The railroads have gotten away with this and really played Biden into a corner here. They didn't negotiate in good faith on this issue of paid time off, and I think they bet that when push came to shove, if they held their line, they'd create a situation where either Biden would have to let a strike happen—that he could be blamed for—or he'd step in and impose a settlement along the lines that he was proposing yesterday, which basically gives the railroads what they wanted.

Would you say that the 1926 legislation was the last piece of progress that rail labor could point to or depend on? Or have they made gains more recently than that?

Railroad workers made gains into the postwar era. In 1946, Harry Truman threatened that if there was a strike, he'd draft the railroad workers. A settlement was reached that averted that, but they didn't get all they wanted in 1946 because of Truman's forcing a settlement through. But it didn't have to get legislated. Railroad unions over time have suffered like all unions in the U.S.—from declining union density, from increased anti-union behavior of management. In the past 20 years or so, you start to see this really taking its toll on railroad workers. I think that's why you're finding some of these workers rejecting this deal.

Is it a different situation for passenger rail workers versus freight rail?

They are not employed by the same people, so that makes it different. Amtrak is a whole different operation that’s partially taxpayer subsidized. Private, profit-making rails in the freight industry are the subject of the worker's complaints. It's different for passenger workers, but a lot of the passenger trains run on track that's maintained by these private rail companies, so it could impact passenger travel as well if there is a strike.

You mentioned that they've been cutting jobs, but not output. So they're just asking for more productivity from fewer workers?

To some extent. Perhaps new technologies have aided [with automation], but not enough to take up the slack for the pressure that it's created for workers. The rail industry, the airline industry—these are highly coordinated national networks that could be easily disrupted by bottlenecks here or there, and they are reliant on highly skilled workers. These are not the kind of jobs where you can call up the local temp agency and they provide somebody to fill in. You're talking about an industry that relies heavily on a small group of truly essential workers. Left to their own devices, these private rail companies have pushed these workers to the wall to try to improve their profit margins over the years. It's become increasingly unsustainable for the workers.

It seems like a bit of a paradox: They're so essential that they could shut down huge parts of the country, which is leverage; but because of that, the federal government is much more likely to intervene to stop them and to side with their employers.

Right. It can go that way, but it doesn't have to go that way. Biden in this case could do what Bernie Sanders is asking be done: insist that the bill include the seven paid sick days. Why not impose a settlement that gives the workers some of what they want? What happened here is: First of all, Biden appointed an emergency panel over the summer that really got it quite wrong in their reading of this. They gave the workers a significant pay increase, but they didn't address this very basic issue, which was central for the workers. And then the possibility of a strike loomed in October, and that's when [Secretary of Labor] Marty Walsh got involved and worked out this tentative deal. But I think the unions [at that time] didn't want to put Biden or the nation through a strike on the eve of an election. The union leaders in good faith tried to cooperate. But even some of those leaders didn't realize the extent to which their own members would say, "No, this doesn't address this key issue."

From the interviews I’ve seen with workers, it seems like almost a matter of dignity. Like, “I put in honest work and I can't even get a paid sick day?”

Oh, very much so. If you look at why workers join unions or go on strikes, very often it's not simply the dollars and cents but like, 'Does this job treat me like a human being? Am I respected?' And here they're told, in effect, 'It doesn't matter how sick you feel, you got to show up.' And it's very dispiriting to be treated that way.

Again, a lot of people in this country work in situations where they don't get paid leave, and what I see in this situation is that these workers are placed in a position of having great leverage, they can bring to the surface an issue which is a real issue for a lot of Americans. Why don't we have a country where people have guaranteed sick leave? Coming out of the pandemic, we could see how important it is when people are sick that they not work. It's bad for everybody if they're coming into work with Covid or something else. So these workers are in a position, in other words, to make a point about a larger policy failure that makes a lot of American workers feel like, ‘Yeah, they don't care about me, they don't recognize my humanity on a basic level.’

Are there other incidents from historical American labor battles that both the unions and the Biden administration could draw on as they try and navigate this?

The great cautionary tale is one I've written a book about, which is the air traffic controller strike. Everybody here needs to make sure this doesn't go down that kind of hole. The problem the air traffic controllers had when they struck was that they were federal employees, so it was illegal for them to strike. But they'd gotten to the point where they couldn't get the government to address basic needs and issues. They were overworked, they were highly stressed, and they couldn't get these things addressed, and it led to a strike.

But the controllers never made an effort to explain their situation to the public, and the public just broadly didn't understand what they were going through. In this case, it's really important that the [unions] explain their case to the public. And I think they've been trying to do that, and I think it's a case that a lot of people can identify with.

Biden can't fire these workers because they don't work for the federal government—like Reagan did—but neither can he actually make them work. Even if the legislation is passed and unions are forced to accept it, we could see rolling sick-outs; we could see wildcat strikes that disrupt things here and there. The phrase in the early 20th century, when miners went on strike and the militia got called out, was, "You can't mine coal with a bayonet." You can't move trains with a law. The law itself is not going to move the trains.

On some level, these workers need to feel heard and that their needs are being addressed. You can try to force something down their throat, but that law is not going to move the trains.

You Might Also Like