Jan. 6 committee never got McCarthy, key Trump aides to testify. Here's who they are.

WASHINGTON – Despite the release of hundreds of transcripts and an 845-page final report, the House committee that investigated the Capitol attack on Jan. 6, 2021, left a variety of questions unanswered.

More than 1,000 witnesses cooperated with the inquiry, but dozens of key figures either defied subpoenas or refused to answer questions by citing executive privilege or because of their Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination.

Ten of the witnesses who defied subpoenas worked in the White House as top aides to former President Donald Trump, were lawyers arguing baseless claims of election fraud or were House Republican allies of Trump who criticized the committee as illegitimate.

Former Vice President Mike Pence, whose life was threatened during the attack, also declined to participate. Among the remaining mysteries is what Trump said to Pence during his tense call the morning of Jan. 6, 2021, when he urged Pence as president of the Senate to reject electors from states President Joe Biden won.

But the most notable no-show was Trump, who also defied a committee subpoena and fought it in federal court.

“Many witnesses hid behind claims of privilege, including Donald Trump himself, who initially blustered that he would be willing to testify but then sued so he could avoid actually facing our questions," the chairman, Rep. Bennie Thompson, D-Miss., and the vice chairwoman, Rep. Liz Cheney, R-Wyo., said in a joint statement Monday.

Here is what we know about 10 of the defiant witnesses:

Mark Meadows: He was central to planning, reacting to Jan. 6, witnesses said

The former White House chief of staff who helped organize former President Donald Trump’s rally on Jan. 6 and coordinated the administration’s response to the riot defied his subpoena. The House found him in contempt, but the Justice Department declined to prosecute him for contempt of Congress.

Meadows comes up repeatedly in transcripts of other witnesses. His aide Cassidy Hutchinson said he held meetings with former House colleagues strategizing how to overturn the 2020 election and routinely burned documents in his office fireplace.

Meadows’ trove of texts, which he gave the committee before deciding not to cooperate, provided messages from lawmakers and Trump relatives urging him to call off the mob while other allies urged him to continue fighting baseless claims of voter fraud.

But Meadows cited executive privilege to protect the confidentiality of his communications with Trump. Biden has rescinded executive privilege for documents and testimony dealing with the attack, which didn't persuade recalcitrant witnesses to testify.

Jan. 6 charges: Will Trump or his allies face charges over Jan. 6? Legal experts explain hurdles DOJ faces

Dan Scavino handled Trump's social media

Dan Scavino, the former White House deputy chief of staff for communications, also defied his subpoena. The House found him in contempt, but the Justice Department declined to prosecute him

Scavino served as Trump’s director of social media such as Twitter but said Trump also wrote his own posts. Scavino monitored social media, where threats of violence appeared for weeks before the riot.

The committee accused Trump of dereliction of duty for not calling off the mob for the 187 minutes between the end of his speech near the White House that morning and when he posted a video urging people to go home. One element that lawmakers said inflamed the crowd came when Trump tweeted at 2:24 p.m. that Pence “didn’t have the courage to do what should have been done” as Pence fled the Senate chamber and the mob chanted to hang him.

Other witnesses said Scavino could provide more insight into the hours-long debate over whether Trump would issue a public statement or even a tweet to call off the crowd.

More: Ketchup, regrets, blood and anger: A guide to the Jan. 6 hearings' witnesses and testimony

Steve Bannon amplified pressure on Pence, committee said

Steve Bannon, a Trump political strategist who defied his subpoena, was found guilty of contempt of Congress and sentenced to four months in prison. His appeal is pending.

Bannon told associates from China on Oct. 31, 2020, Trump would falsely declare victory even if he lost the election and said it would be a “firestorm.”

In a podcast, Bannon said Pence “spit the bit,” meaning he was no longer supporting Trump’s efforts to overturn the 2020 election, which the committee described as amplifying the pressure on Pence.

Bannon called Trump at least twice on Jan. 5, 2021.

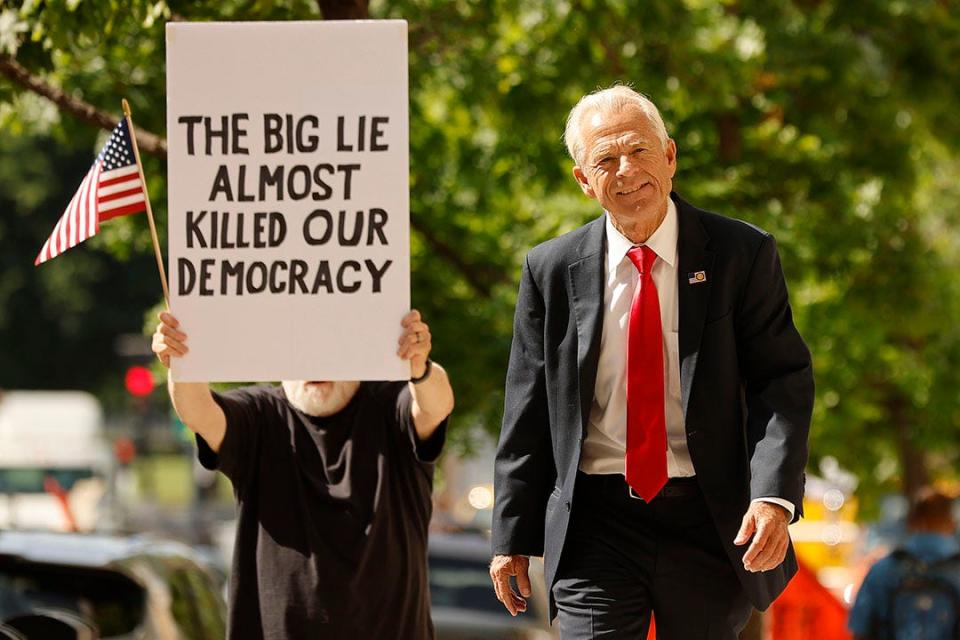

Peter Navarro focused attention on Pence

Peter Navarro, the former Trump trade adviser defied his subpoena and awaits trial Jan. 30.

Navarro, the director of the White House office of trade and manufacturing policy, referred to the strategy for having Pence overturn the election as the “Green Bay Sweep,” named after one of the football team’s running plays.

Navarro called Pence the quarterback who could delay certification of the election. Navarro described the strategy in his book: “In Trump Time: A Journal of America’s Plague Year.” The committee said the account explained why Trump loyalists became fixated on Pence.

But Pence refused to participate. In one book passage, Navarro compared Pence to Brutus, a Roman politician who helped assassinate Julius Caesar.

Jeffrey Clark sparked DOJ resignation threat with bid for attorney general

Jeffrey Clark, a former Justice Department official who sought to become Trump’s acting attorney general, refused to answer questions by citing executive privilege

Clark, a former assistant attorney general for the environment, drafted a letter for the attorney general to send to states falsely asserting the Justice Department found fraud and urging state legislatures to convene and change their electors. Clark sought to replace Acting Attorney General Jeffrey Rosen in order to send the letter.

In a three-hour Oval Office meeting on Jan. 3, 2021, top Justice Department and White House lawyers threatened to resign if Trump elevated Clark. Pat Cipollone, the White House counsel, called Clark’s letter a “murder-suicide pact” between the administration and state lawmakers.

As Clark refused to answer committee questions, his lawyer Harry MacDougald said the panel was illegitimate because of how it was organized even though federal courts upheld its subpoenas. “You are railroading Mr. Clark, publicly abusing him and threatening him with criminal prosecution on a completely spurious legal foundation,” MacDougald said.

John Eastman devised Trump strategy to overturn 2020 election

John Eastman, one of Trump’s personal lawyers, refused to answer substantive questions under his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination.

Eastman devised the strategy to have Pence reject electors from key states Biden won, in anticipation state legislatures would change their electors or the race would be decided in the House, where Republican delegations outnumbered Democrats.

Eastman acknowledged the Supreme Court would likely reject the strategy unanimously, according to Pence aides.

U.S. District Judge David Carter ruled that Eastman had to provide most of his emails to the committee, despite claims of attorney-client privilege. In that civil lawsuit, Carter ruled that Eastman and Trump “more likely than not” acted unlawfully to obstruct Congress. “The illegality of the plan was obvious,” Carter wrote.

The committee urged the Justice Department to charge Eastman and Trump criminally.

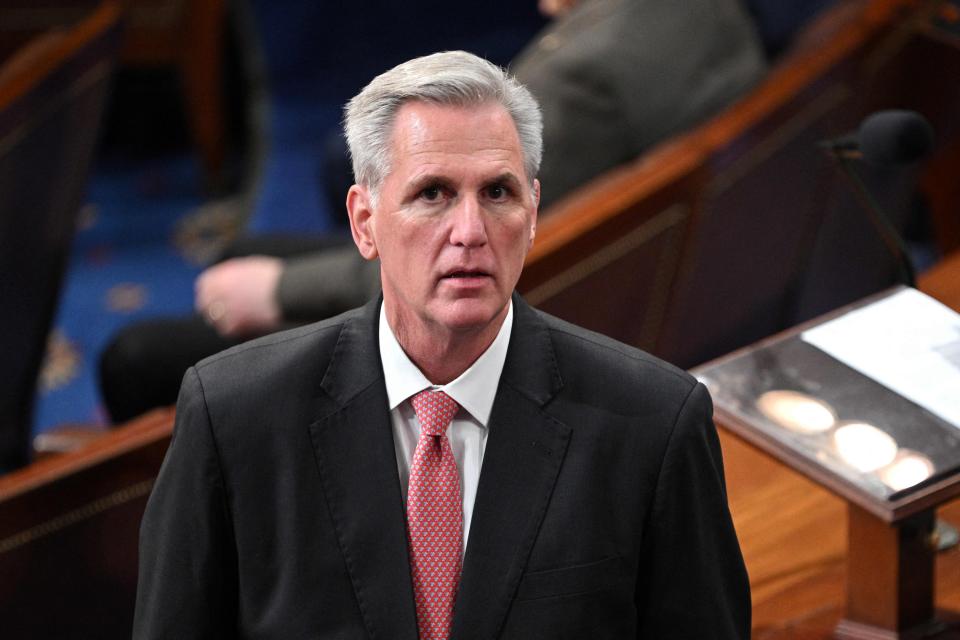

Kevin McCarthyHouse Republicans defied subpoenas they called illegitimate

Republican Reps. Kevin McCarthy of California, Jim Jordan of Ohio, Scott Perry of Pennsylvania and Andy Biggs of Arizona each defied a subpoena and criticized the committee as illegitimate and partisan.

The committee referred the four to the Ethics Committee for potential inquiries, but little is expected because the panel is evenly divided between the parties.

Here is what we know about each of the lawmakers' roles dealing with Jan. 6, 2021:

McCarthy spoke with Trump on Jan. 6, when Trump told him: “I guess they’re just more upset about the election theft than you are,” according to former Rep. Jaime Herrera Beutler, R-Wash. McCarthy said on the House floor on Jan. 13, 2021, “The president bears responsibility for Wednesday’s attack on Congress by mob rioters.” He told Republican lawmakers he would urge Trump to resign. But he later supported Trump and received his endorsement to become House speaker.

Jordan also spoke with Trump on Jan. 6, 2021, and had participated in numerous post-election meetings with White House officials and Trump’s personal lawyer, Rudy Giuliani. Jordan led a Jan. 2, 2021, conference call for Trump and lawmakers to discuss strategies including encouraging the president’s supporters to “march to the Capitol” on Jan. 6, 2021, according to the committee.

Perry introduce Clark to Meadows and to Trump. Perry was present for a meeting where members of the White House counsel’s office explained Trump’s strategy to submit fake electors wasn’t legally sound, according to the committee. Perry also participated in post-election meetings to discuss strategy to overturn the election.

Biggs also participated in the post-election strategy sessions. He texted Meadows on Nov. 6 urging him to “encourage the state legislatures to appoint” fake electors, according to the committee. Biggs coordinated with Arizona state Rep. Mark Finchem to gather signatures from lawmakers endorsing fake electors and Biggs contacted fake electors in at least one state seeking evidence of voter fraud, the committee said.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: McCarthy, Trump: The key January 6 witnesses who refused to testify