To Be Italian-American Is to Be Antifascist. It’s Time We Acted Like It.

After bonding over overpriced cheeses and tall-tales about our Southern-Italian nonni on our first date, my now-partner admitted to me that she felt relieved. “I was worried we wouldn’t get along,” she said. “Your profile said you were Italian-American.”

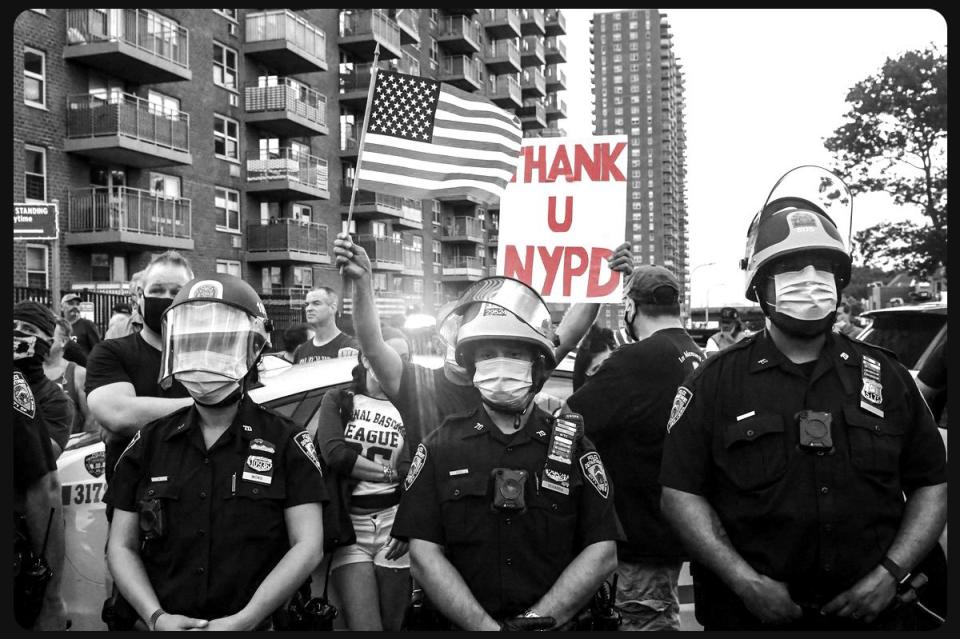

It occurred to me then that the two of us had opposing preconceptions about each other. I’m a fourth-generation Italian-American. My great grandparents were the last to reside on the Peninsula, and I was elated to meet someone who shares my cultural heritage. My partner's parents were born in Italy, though. She’s first-generation. So when Italian-Americans show up in the news doing despicable things–like, say, some of the cavones who were videotaped this summer spitting on Black Lives Matter protestors in South Brooklyn, hurling racial slurs, telling them to “get raped”–the shame stings a bit differently for her. And it was about to get a lot worse.

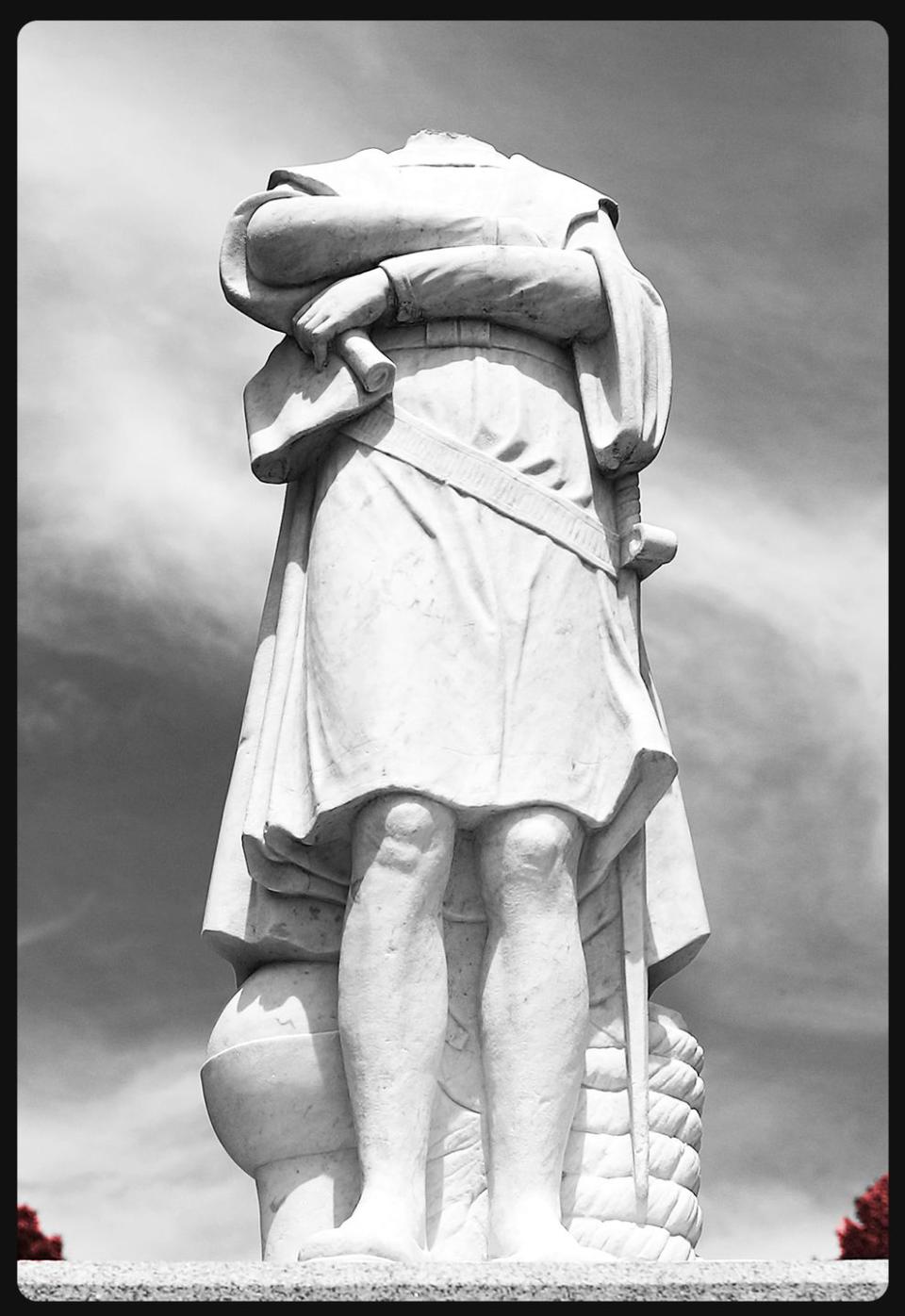

Today is the federal holiday known as Columbus Day. I personally choose to recognize Indigineous People’s Day instead, but for some Italian Americans, the holiday—and the man himself—have become something of a cultural flashpoint. As recently as August, a professor from SUNY Buffalo State College published an open letter denouncing the removal of Columbus statues as an “affront...to the entire literate world.” Meanwhile, Baltimore, and a number of other cities around the nation have put forth legislation to officially rename the day to honor the Native American people. The boxing match goes on and on.

Perhaps, having gotten this far, you can guess my stance on the 15th-century colonizer who’s partly responsible for the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. That’s not to say he makes me ashamed of my heritage. But I struggle to see statues of Columbus as any way to honor my Southern-Italian ancestors. Part of that is simple, geographical: Italy wasn’t a unified country until the late 1800s, so even if you believe that Columbus was born in the Northern region of the Peninsula (which is itself only a possibility at best), he might as well have hailed from a different country entirely. But the other part of it is more gut-wrenching: After this summer, it’s been pretty damn hard to feel any pride for my people at all. And a little over a year after that night with my partner at the wine bar, I think I’ve finally come to understand why she was so reluctant to date another Italian-American.

It wasn’t just the counter-protestors in South Brooklyn. We saw Italian-Americans all over social media this summer, screaming at their front-facing phone cameras about the 2nd amendment, their right not to wear masks, or, as I’ve now come to expect, their precious Christopher Columbus. On Facebook, five different communities currently don the title “Italian Lives Matter.” The sixth is called “Italian Blue Lives Matter.” But the ignorance goes further than social media. This sort of belligerent pride has, like a garlic burp, traveled all the way up to the White House.

On July 15, Rudy Giuliani, perhaps the most vocal and longstanding Italian-American political figure, said that Black Lives Matter wants to “take our property" and give it to Black people. At his Tulsa rally in June, Trump praised “the I-Tail-Eyans” for defending the Columbus statue in New York City. “They didn’t have too much of a chance,” referring to the “left-wing anarchists” who were apparently scared away by the resolute, patriotic Italian-Americans of the president’s Rocky Balboa fantasies. Governor Cuomo even agreed that, despite representing a genocidal conqueror, statues of Columbus should be upheld, saying that they “signify appreciation for the Italian-American contribution to New York.” All while his younger brother Chris compares Italians being called “Fredo” to Black people being called the n-word. Madonn’.

It’s a goddamn shame that so many Italian-Americans seem ignorant, perhaps willfully, about our heritage. Many of us can recite the entirety of The Godfather from memory while having no clue about the real-life history behind the immigrant experience that’s portrayed in that film. It’s a shame because our actual history is a lot more colorful–and radical–than a bunch of statues and stereotypes.

If you spend some time studying the Italian diaspora, you find a very different image of Italian-Americans than the baseball bat-wielding goombahs who were reported chanting “All Lives Matter” in the Bronx as recently as September. The majority of Italians didn’t leave their homes just in search of better lives. They came here, mostly from the South, fleeing poverty, feudalism, and oppressors who were a lot like Columbus. I should point out that, through the generations, America also saw its fair share of Northern Italians, too; the Peninsula was left quite unbalanced after its unification and our young nation presented untold opportunities. But, still, even if you believe that Columbus would’ve called himself an Italian, even if your family is from the North, the colonizer—whose expedition was sponsored by the Spanish crown—seems about as accurate a symbol for our people as Chef Boyardee (and at least Ettore Boiardi was definitely Italian).

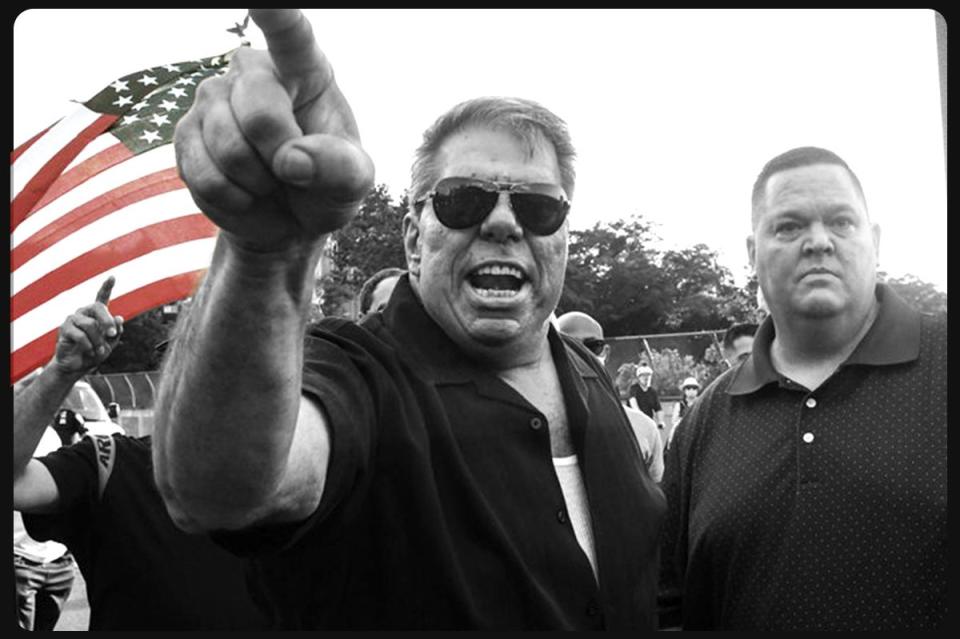

My beef (or braciole, I guess), isn’t really with Columbus, though. Not that he doesn’t sound horrible, because he absolutely does. But the man has also been dead for more than 500 years. It’s the Italian-Americans today who parade around in his name that worry me. Because there’s something about Columbus that seems to rile up a sort of malignant pride in Italian-Americans, one that’s based on a fantasy narrative–and a misinformed and harmful one at that. “We’re here, as Italian-Americans,” a Chicago demonstrator yelled in a Daily Caller video that surfaced in early August, “to ask these protestors...Why are you constantly picking on Columbus?...You may disagree with us, you may not like him, your history is different than our history. But I want to tell you something: We did it the proper way! We got our people elected. We worked hard in the streets. And we did it the American way.”

What is the “proper way,” though? What is the “right way?” And how does the unignorable existence of African-American slavery fit into this tidy narrative?

Believe me, I hate railing against people who remind me of my uncles, cousins, and my late grandfathers. Of course I want to find common ground with the folks who share my lineage. Why wouldn’t I? But while this demonstrator is right to say that our people “worked hard” when they arrived in America, if he understood that we arrived here facing echoes of the same sort of xenophobia and prejudice we’re seeing today, he’d understand the irony in his protection of symbols of oppression. When Italians came to America, after fighting government oppression in their home country, they brought that fight with them. In some cases, such as in the government execution of anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, or the lynching of eleven Italian-Americans in New Orleans–they died for it. And Columbus day? That was created only after decades of suffering discrimination, police killings, and generational government oppression. Many Italians say Columbus Day was given to us in remembrance of these horrible years–others, however, argue it was the American government’s way of making us forget.

Since that date last September, my partner has, in her words, turned me into a real “Bella ciao” paisan. “Bella ciao,” as I’ve learned, is the name of the famous Italian folk song that became the anthem of the country’s antifascist movement. Sure, she’s taught me how to throw together a pot of ciambotta. And I can comprehend all sorts of Napoletan dialect words now. But I’ve also learned how to better honor the radical parts of my heritage, too. She introduced me to the “leftists of the italian diaspora” Facebook group, which has become a constant source of refuge for me these days. In there, Italian-Americans share academic articles, family anecdotes, and essays about our ancestors’ history of protest, such as “Antifa, the American Movement with Italian Roots and the Same Enemy: Fascism,” from the publication La Voce Di New York. “While Italy has the shame of having spawned the first fascist regime,” writer Stanislao Pugliese explains, “it can boast of having generated the first anti-fascist movement as well.” Until recently, I didn’t even know that this sector of the Italian-American community even existed.

After joining this Italian leftist group, I’ve discovered (and signed) several petitions in favor of removing Columbus statues, such as Buffalo, New York’s “Not in Our Name” petition, or “Contro Colombo - Philly Italians Against The Colombus Statue.” The latter states, “The violent mob that gathered at Marconi Plaza in South Philadelphia to ‘protect’ a Columbus statue...made it clear that there is a stubborn commitment among many Italian Americans in Philadelphia to mythologize figures known for their brutality and bigotry.” Frank Rizzo, the former mayor and beloved figure for so many Philadelphia Italian-Americans, as the writer goes on to explain, has a “legacy of terror for Black, brown and LGBTQ Philadelphians.” This legacy includes the MOVE bombing, an appalling act of government violence in which Rizzo’s Police Department dropped a bomb on a West Philadelphia rowhome occupied by the Black liberation group MOVE, killing eleven people, including five children, and destroying sixty-one homes in the area. As per the Rizzo monuments in Philly? Contro Colombo wants them removed too.

Philadelphia, as we’ve seen from stories about Brooklyn, Chicago, and Boston, is not the only American city bogged down by these sort of bigoted demonstrations. Italian-Americans–who Buzzfeed reported in 2016 to be among the largest group of white people to vote for Donald Trump–have become as well-known for their cuisine as they have for their self-righteousness. HBO’s The Sopranos, as it always does, comes to mind here. Series creator, David Chase, faced the barbed edges of the prideful Italian-American community when he tried to film an episode of his show in Essex County, New Jersey. As described in Brett Martin’s Difficult Men, Italian-Americans in the area had boycotted the series for its negative representation of the community. Because of the protest, Chase was forced to relocate production, and was apparently furious. “How can these people cling to their victimhood so much?” Chase, himself an Italian-American from New Jersey (it was originally DeCesare, not Chase), writes in the book. “These mingy little barbers. Italians are very successful people. Why is it so important to stay a beaten, suffering minority? It makes me sick.”

And yet, that’s really the defining quality of the Italian-American stereotype, at least the one that’s been popularized by underdog stories like the Rocky film series, which Adam Serwer in The Atlantic rightfully points out, “sees a black boxer humbled by a white challenger in every single movie.” He writes that Rocky is a “product of a sense of white pride and humiliation, and the desire to overcome it by restoring the proper order of things.” I’d only add that it’s no surprise that this white challenger, however, turns out to be an Italian-American with a victimhood complex.

This strange obsession with victimhood: You hear it everywhere from the blatantly racist argument that Chinese people and members of other ethnic groups “took over” the Little Italys of the country, to the bogus assumption that low-income areas of cities were safer when they were filled with Italian immigrants. And now, of course, with the biggest self-proclaimed victim of all time in the White House, this mentality is not only validated on a daily basis, but encouraged. It is a fantasy, though. Italian-Americans have not been oppressed for generations now. We don’t need to “take our country back.” Our people hold office. We line the gated communities of suburban developments. Pizza is as American a food as apple pie. As Chase says, we are “very successful people,” indeed.

When I began work on this essay a few months ago, I felt some hesitation. I didn’t want to be another distraction; Italian-American ignorance is by no means a problem as dire as police violence or government negligence during the coronavirus pandemic. But my partner compelled me to keep digging, and eventually I struck the core of it–shrouded in the grassy shadows beneath every statue of Columbus is a righteous history of Italian antifascism. If there’s anything Italian-Americans need to take back, it’s our capacity for empathy. Because, to be Italian-American is not just to love Ladri di biciclette (The Bicycle Thieves) or your Nonna’s chicken parmigiana recipe. To be Italian-American is to be antifascist. It’s a proud tradition of protest in our heritage that has gone largely forgotten. And today, when the democratic values of our nation are threatened like never before, when Trump himself emulates Benito Mussolini, presiding chin-up over the South Lawn as if looming over his own personal 1930s-era Piazza Venezia, I realized I could use this essay to remind Italian-Americans what we’re made of. After all, it was Mussolini who, before Trump, was quoted as saying “Make American Great”–and we all know what the Italian people ended up doing with him.

You Might Also Like