“Hyperscale” Weapons Factory Vision Outlined By Anduril

Defense technology contractor Anduril has announced plans to build a novel “hyperscale” production facility that will be able to churn out huge numbers of different military products, including uncrewed combat aircraft and autonomous underwater vehicles. The project closely aligns with the Pentagon’s aim of securing the ability to manufacture at scale, to meet future demands, especially for uncrewed systems that are increasingly seen as being critical in potential peer-state conflicts.

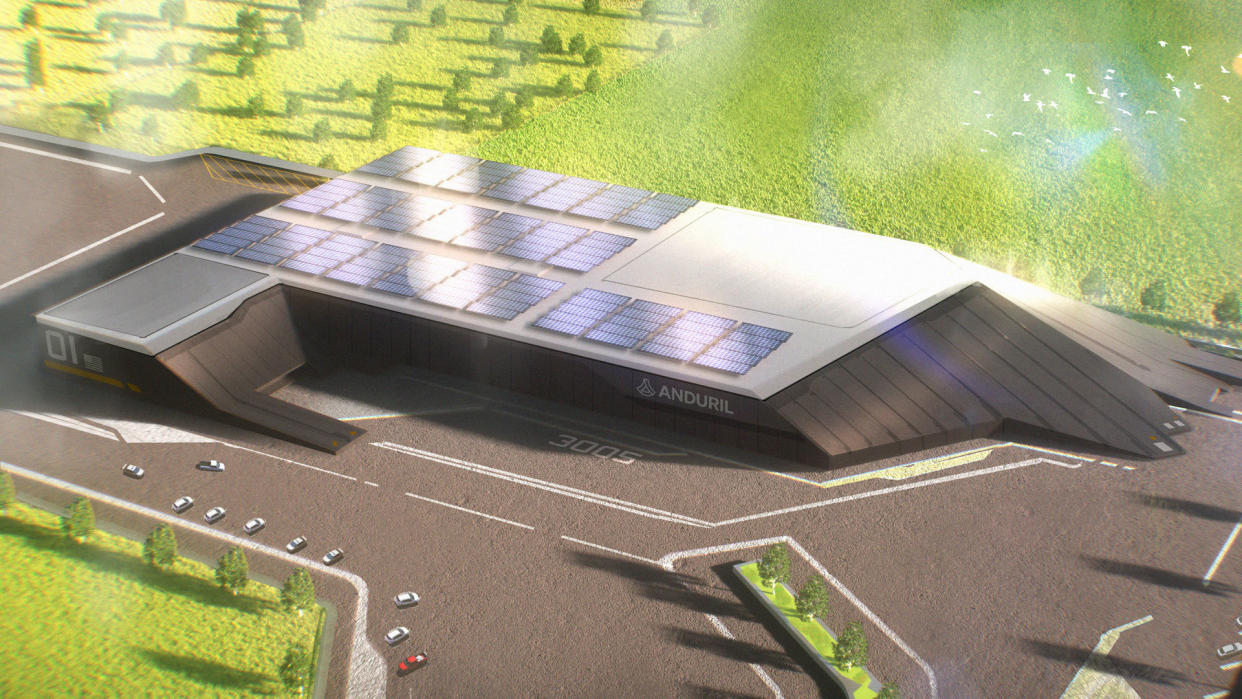

The California-based company announced today that it will build the first so-called “Arsenal facility” in the United States, using funding from a recent $1.5-billion Series F investment round. In a document titled Rebuilding the Arsenal of Democracy, Anduril lays out plans for the manufacturing facility, which will measure more than five million square feet and, once up and running, will be able to “produce tens of thousands of autonomous weapons systems addressing the urgent needs of the United States and our allies.”

Anduril says it sees a need for “a new paradigm in defense production,” in which the defense industrial base is configured to provide the quantities of autonomous systems, weapons, and munitions needed to achieve “affordable mass.” This means that the defense industry across the board will need to produce “orders of magnitude more than it is currently producing today.”

The company identifies what it sees as key limitations in the traditional defense industrial base, in particular how it struggles to scale production to meet demands.

“Slow and low production rates, inflexible processes, and the development of exquisite, defense-specific, bespoke systems have hindered the ability to respond quickly to need,” Anduril says. “Lead times to replenish key weapons and munitions average two years.”

These problems have been brought into sharper contrast by the war in Ukraine, in which the U.S. manufacturing base has been unable to keep up with demand, both to arm Ukraine but also to replenish its own stocks after the transfer of weapons to Kyiv.

A good example of this is the significant difficulty in replenishing stocks of Stinger air defense missiles supplied to Ukraine, an effort that has been estimated to take two to three years and which would be impossible without experienced workers being brought out of retirement.

“In a major conflict, use of weapons and munitions would quickly exceed supply,” Anduril continues, predicting that the United States would run out of weapons “in the first few weeks” of a peer-state war. A conflict with China, meanwhile, would see U.S. weapons expended after less than a week of fighting, the company predicts.

In particular, the company points to the different numbers of weapons to be procured in the Fiscal Year 2024 budget request, including 118 Long-Range Anti-Ship Missiles (LRASM), 39 Standard Missile 3s (SM-3), 125 Standard Missile 6s (SM-6), 34 Tomahawk cruise missiles, and 550 Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missiles — Extended Range (JASSM-ER).

USN

As well as costing several million dollars apiece, the United States currently lacks the capacity to ramp up production of such weapons. As a result, the United States and its allies “would run out of these and other critical munitions in a matter of days in a war against China and then struggle to replace them on a relevant timeline.”

Anduril sees the solution in adopting the same kinds of agile, rapid, and scalable processes found in the commercial manufacturing sector, but which have typically been absent from the defense industrial base.

At the center of the company’s ambitions is the Arsenal facility, described as “a software-defined manufacturing platform optimized for the mass production of autonomous systems and weapons.” To ensure that the manufacturing plant can achieve hyperscale, it will rely on four principles: designs that are optimized for simplicity and scale; a resilient supply chain; software-defined production; and the central infrastructure itself.

To start with, Anduril will build Arsenal-1, suggesting that ultimately the plans are for a chain of similar production enterprises across the United States, and potentially elsewhere too, dependent on requirements. According to reports, the location of the flagship U.S. plant is yet to be determined.

Currently, Anduril has major production facilities in California, Mississippi, Rhode Island, Georgia, and Sydney, Australia.

As to the actual products that will come out of the Arsenal-1 facility, Anduril says that “nearly 90 percent” of its designs are compatible with manufacturing at hyperscale, using commercially available components and materials.

Leveraging existing capabilities in the commercial sector will also see Anduril look to recruit personnel from there, as it builds toward hyperscale production.

“We’re taking many of the people who lead those processes at some of these world-leading commercial companies that have achieved this type of hyperscale production before and we’re bringing this into the defense industrial base to fundamentally transform how we build weapons, how we design weapons,” Chris Brose, Anduril’s chief strategy officer, said.

It’s also worth noting that Anduril is not the only U.S. defense contractor looking at the potentially transformational value of new, purpose-designed production facilities. Two of the more established U.S. aerospace players have also recently announced plans to set up new manufacturing facilities for advanced programs.

Boeing has invested around $1.8 billion in a new manufacturing center in St. Louis, Missouri. This is optimized for the production of advanced combat aircraft, is due to be completed in 2026, and would likely manufacture the crewed fighter component of the U.S. Air Force’s Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) initiative, if the Boeing bid is successful. Lockheed Martin, too, has opened a new cutting-edge manufacturing facility at its campus in Palmdale, California, described as a “factory of the future.” The facility, which is part of the famed Skunk Works advanced projects division, is intended to accelerate and optimize the designs and production of advanced aerospace vehicles, including stealth fighters, drones, and hypersonic missiles. You can read more about it here.

Notable programs and products in Anduril’s portfolio include the Ghost Shark extra-large autonomous undersea vehicle (in partnership with Australia), the Roadrunner reusable missile-like air vehicle, and the Iris family of passive infrared sensors. The company is one of two vendors building aircraft for the first increment of the U.S. Air Force’s Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA) advanced uncrewed aircraft program and is also understood to be developing technology for the Replicator low-cost drone effort, more on which later.

While these involve cutting-edge technologies and high-end capabilities, Anduril is confident these systems can be produced rapidly and in large numbers.

The company draws a parallel with the U.S. defense manufacturing effort in World War II, in which Ford assembly lines, for example, were repurposed to produce B-24 bombers without great difficulty. Today, it would be impossible for the Ford plant in Detroit to build B-21 stealth bombers — or most other advanced military platforms, for that matter — a problem that Anduril thinks it can help to resolve through its hyperscale production plans.

The idea of the U.S. defense production model trading traditional complexity for more simple designs, with the minimum of unnecessary materials, parts, and specialized processes, combined with software-based production is hardly a new one. It has previously been pitched as the answer to the demand for defense equipment that can be produced rapidly and in mass, while at the same time offering the potential to quickly adapt products in response to emerging requirements.

For Arsenal, Anduril highlights what it describes as “a unified system to integrate the design, development, and mass production stages for all Anduril products. Arsenal consists of a common enterprise resource planning system and a proprietary manufacturing execution software system to integrate threat-based operational analysis, modeling, simulation, drawing, testing, bill of material management, work orders, production, and data management across the product lifecycle.”

Overall, the concerns that Anduril identifies are very much already driving different U.S. efforts to field thousands of uncrewed vehicles, including the aforementioned Replicator program.

As you can read about here, Replicator has been very squarely set up to counter China’s rapid military progress and plans to rapidly field “thousands” of attritable autonomous platforms that will be characterized by being “small, smart, cheap, and many.” As in Anduril’s vision, Replicator seeks to harness U.S. innovation as a way to counter the mass of China’s armed forces, while relying heavily on uncrewed systems.

Anduril

Then there is the Air Force’s CCA, also based around highly autonomous drones, which will work closely together with crewed combat jets. The service plans to acquire 100 CCAs under Increment One, while Increment Two will build toward an ultimate goal to acquire and field 1,000 CCAs, and perhaps many more. Central to CCA is the requirement to accelerate development timetables, and then quickly ramp up large-scale production of finalized designs, very much at the core of Anduril’s plans.

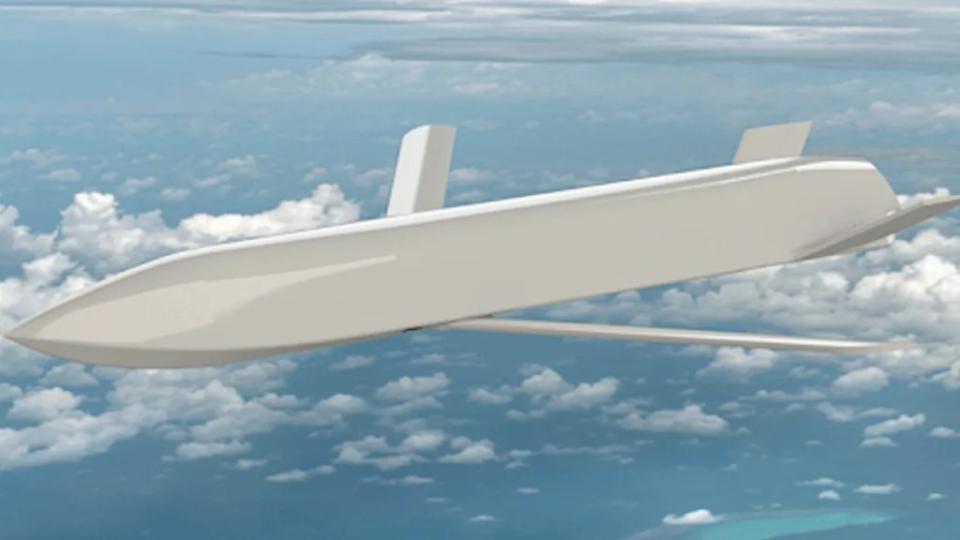

Anduril and its Fury design are currently competing against a rival General Atomics drone, which uses components originally made for the MQ-9 Reaper. There are suggestions, however, that both types could eventually enter service as a complementary team.

Another Air Force project that parallels Anduril’s vision is the Enterprise Test Vehicle (ETV) program, which aims to explore the potential of low-cost air vehicles that could be turned into cruise missiles, but which could also undertake electronic attack missions and other roles. In this case, the service is looking at how the available industrial base could be optimized to produce greater numbers of more affordable weapons, again with the demands of a future high-end conflict, such as one against China, at the forefront. Anduril is one of the companies that has been selected to design, build, and flight-test an ETV concept.

Ultimately, Anduril is also banking on the U.S. military and its allies making a dramatic shift away from heavily focusing on “exquisite” weapons toward cheaper, more autonomous, mass-producible ones.

The kinds of weapons that currently fall into this category, however, are chiefly smaller, tactical, shorter-range systems of the kinds now familiar from the war in Ukraine, as well as other combat theaters. For the future, these systems will not only have to be more affordable, autonomous, and be produced in large quantities, but they will also need to be bigger and more capable, offering greater range and payload, as well as enhanced survivability. This is especially important for future contingencies across the vast expanses of the Indo-Pacific region.

Anduril admits that its vision of hyperscale defense production might seem “fanciful,” but the company is confident it can be achieved. Anduril argues that by harnessing the existing raw materials, technology, and personnel, its ambitious targets can be met, and the U.S. defense industrial base overhauled to meet future demands. The key thing, the company believes, is the political conviction to change the way things are done.

That will likely prove easier said than done, but the software-driven Arsenal facility is, at the very least, a compelling argument for doing things differently. Whether it’s the whole solution to a growing problem or a part of it, remains to be seen, but it’s very clear that the drive toward scaling production — especially of uncrewed systems and weapons — is currently a key concern across the Pentagon.

Contact the author: [email protected]