Some hurricanes suddenly explode in intensity, shocking nearly everyone (even forecasters)

Janalea England started the morning of Aug. 29 last year preparing her home and seafood market for Hurricane Idalia. The National Hurricane Center's forecast called for landfall somewhere near Steinhatchee, their small community on the Gulf of Mexico by the next morning.

At their Steinhatchee Fish Market, she brought things in from outside, threw away any older seafood and packed the rest into the freezer, then headed home.

Like many who routinely experience tropical storms and hurricanes, they were somewhat blasé about Idalia, approaching from the Florida Keys with 85 mph winds at that point, England said. "We were preparing to be without power more than anything."

After finishing preparations, England and her daughter rode back through town, blasting “Under the Sea” from Disney's "The Little Mermaid" on the stereo and filming a Facebook live video. Now she wishes she’d saved the videos, to compare what Steinhatchee looked like before the storm.

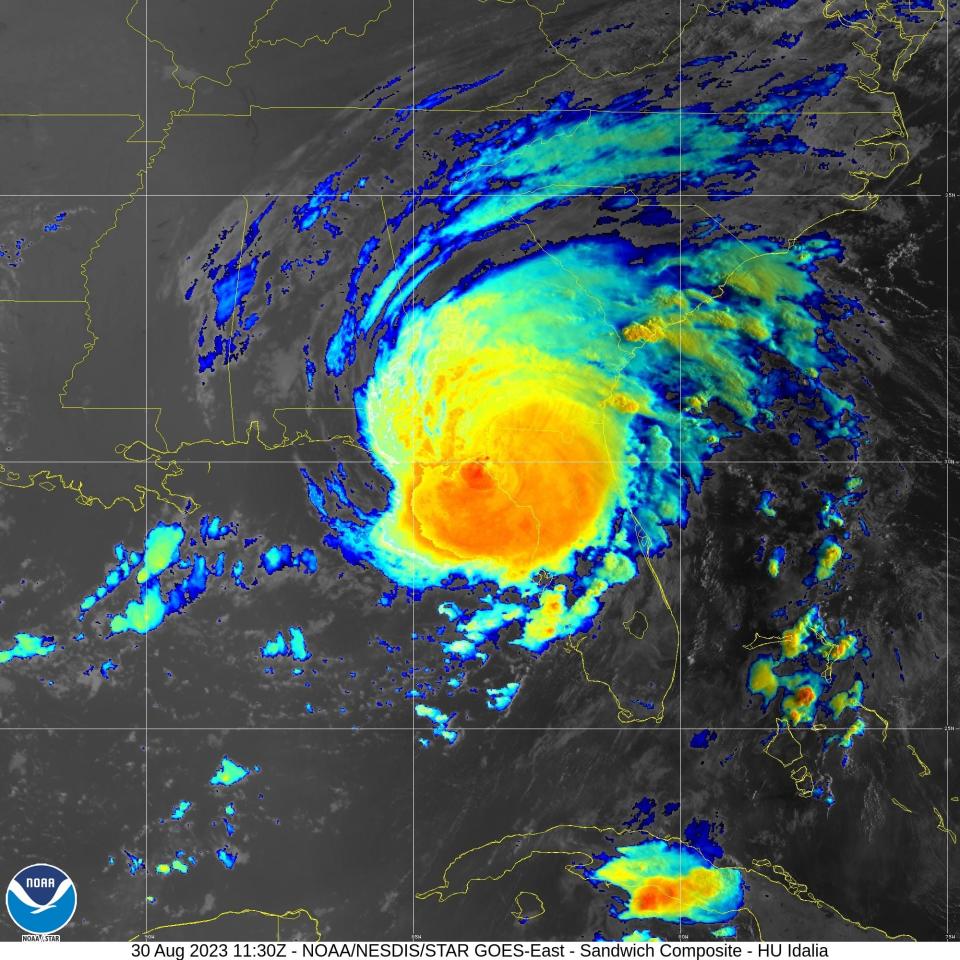

Between their ride through town and the time Idalia began battering the coast between 3 and 4 the following morning, the storm exploded, becoming a powerful hurricane with 130 mph winds in a phenomenon meteorologists call rapid intensification.

Although Idalia began to diminish almost as quickly before making landfall, Steinhatchee suffered major damage when the storm delivered an 8-12-foot storm surge.

The community, like others all along the Gulf Coast, continues to recover, even as another Atlantic hurricane season begins Saturday.

Outlooks for the six-month season call for above average activity, with at least two forecasts predicting more storms than they've ever predicted before. Colorado State University predicted 11 hurricanes and 23 named storms. The National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration predicted 17 to 25 named storms, with 8 to 13 hurricanes.

No one knows how many of those potential storms will make landfall or where, but it's a repeat of storms like Idalia that worry forecasters the most – the kind with names that often live in infamy.

They're the storms that intensify rapidly — quickly building ferocious wind speeds, becoming powerhouses almost overnight. All four of the most destructive, Category 5 landfalling hurricanes of the past 100 years – the 1935 Labor Day Hurricane, Camille, Andrew and Michael – underwent rapid intensification.

Your annual reminder that crazy things can happen:

All four Category 5 hurricane landfalls on the continental U.S. were from storms that were not even hurricanes just *three* days before making landfall!

It's critical to be vigilant and prepared throughout hurricane season. pic.twitter.com/bCT1rmEwbN— Brian McNoldy (@BMcNoldy) May 21, 2024

The process has been notoriously difficult to forecast, defying meteorologists for years. For reasons not fully understood, the storms are able to make the most of the surrounding conditions.

However, the hurricane center and the computer models it uses to develop forecasts have begun to see greater success with forecasting such rapid intensification, thanks to advancements in technology, data collection and modeling.

"We actually have the tools and the confidence to be able to do it, and we were pretty successful in Idalia," said Michael Brennan, director of the National Hurricane Center. But the forecasts and a suite of models were less successful in predicting the transformation of Hurricane Otis in the Eastern Pacific last year.

What is rapid intensification?

The official definition of rapid intensification is an increase in wind speeds of about 35 mph in 24 hours. Idalia did that in 15.

When Idalia became a tropical storm and moved into the Gulf of Mexico on Aug. 29, it found a warm, steamy sauna, full of the heat and moisture that helps make hurricanes stronger by providing lift, which builds towering cloud structures at the top and lower pressures at the surface.

When conditions inside and outside a storm are perfect, with warm water, low wind shear and lots of moisture, a storm can explode. It happened twice as Hurricane Ian loomed toward a landfall in Southwest Florida in 2022.

Scientists are still trying to understand more about what happens, and exactly why the storms can develop catastrophic winds so suddenly and with so little warning.

"You can have what seems to be a favorable environment but not have the structure of the storm to really take advantage of that," said Dan Brown, branch chief of the center's hurricane specialist unit. "Other times the storm might have more of that structure, but the environment's a little marginal."

Then sometimes when they forecast rapid strengthening, he said, the storm can increase at an incredible rate, even a higher rate than the forecast.

Hurricane season starts Saturday. See which previous storms passed near your neighborhood.

As Idalia continued to rapidly intensify offshore between 3 - 4 a.m. on Aug. 30, the winds already arriving on shore sent England, her husband Garrett, their three children and his parents into the master bathroom, where they huddled for safety for hours, reading the Holy Bible and praying as terrifying winds that sounded like mini tornadoes shrieked outside their home.

Idalia made landfall at Keaton Beach around 7:45 a.m. on Aug. 30. The Englands escaped damage at home or at the seafood market. Their business became a temporary distribution center for people donating supplies and a meal preparation station for volunteers cooking for residents and first responders.

Is rapid intensification happening more often?

Some signs point to more frequent rapid intensification events, Brennan said, making it even more crucial to continue improving their ability to forecast these storms.

Scientists are still trying to determine what impact the warming climate might be having on tropical cyclones, but rapid intensification is expected to increase, according to Tom Knutson, a senior scientist with NOAA's Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory who maintains an overview page on global warming and hurricanes.

A 2019 paper Knutson co-authored with a team led by colleague Kieran Bhatia suggested increasing greenhouse gases contribute to a detectable increase in rapid intensification in tropical cyclones.

Forecasting rapid intensification used to be nearly impossible

For years, intensity predictions were the hurricane center’s biggest nemesis. And forecasting rapid intensification was like “the forbidden zone,” said Brian McNoldy, a senior hurricane researcher at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric and Earth Science. It was considered “extremely difficult," he said, to have confidence that it would happen and to get the timing right.

That the center correctly predicted the possibility of rapid intensification within Idalia some 36 hours in advance is "amazing," McNoldy said.

The center wasn't even making rapid intensification forecasts 10 years ago, Brennan said. But in the last five years, they've begun making "significant progress."

Forecasting ability is improving because of the advancements NOAA and its partners have made in the quality and quantity of data and information being fed into the various hurricane models that help predict intensity, Brennan said. Dropsondes, drones and other tools provide more information than ever – and at higher resolution – about winds, moisture, temperature and other conditions inside and all around the storm.

Among the improvements NOAA plans to data collection this year are:

Two model additions to help understand hurricane intensity and predict the probability of rapid intensification

Upgraded coastal weather buoys to improve measurements of wind speed and direction

Additional drifting buoys, Saildrones and underwater gliders

A lighter weight form of dropsonde, called Streamsondes, will be added to the mix to collect a broader array of real time observations.

"We’ve seen some improvements in (forecasting) rapid strengthening ... but we still have a ways to go to really make this forecast exact as we can," Brown said.

Hurricane Otis defied the forecasts

Otis showed the ground left to cover. Meteorologists watched in horror as it exploded in intensity while approaching the coast of Mexico.

"None of the models were successful with Otis," Brennan said. "There was little to no model guidance that indicated much more than just sort of average strengthening."

The transformation was "incredible,” said Robbie Berg, a senior hurricane specialist at the center. “We’ve seen rapid intensification before, but it happened right on the doorstep of Acapulco."

The hurricane's winds increased from 80 mph to 165 mph in just 10 hours as it approached the beachside city of Acapulco, Mexico. Making landfall at 1:25 a.m. as a Category 5, it killed at least 52 and caused an estimated $12 to $15 billion in damages.

“I think what scares us is that it could happen in the United States,” Berg said. “Look at a big city like Miami or Houston or New Orleans. There's nothing stopping a storm from behaving the same way near our coastline.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Hurricane season 2024: This is one of forecasters' biggest worries