Hurricane track forecasts have hit a wall but new modeling may give them a boost

Decades of improvements in forecasting the track of a tropical cyclone have led to a skinnier and more precise hurricane cone but this year will see no further refinement.

Some of the blame falls on a wily tropical storm from 2023 that evaded official predictions, spoiling the average track error rate so that this season's notorious cone of uncertainty will bulge in some places and remain virtually unchanged in others.

And experts caution that gains made in divining the path of a blustery menace are slowing, if not idling.

“I think we are definitely at some sort of limit, not the limit, but improvement has been flat at least the past five to six years,” said John Cangialosi, a senior hurricane specialist with the National Hurricane Center (NHC). “Why it’s happened is a hot topic that no one can really answer.”

2024 hurricane season: Forecasts all point to a busy season with La Ni?a and warm ocean temps

With the June 1 official start date of hurricane season coming soon, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is looking to a new weather prediction model called the Hurricane Analysis and Forecast System, or HAFS, to boost track and intensity forecasts.

HAFS, which uses weather and climate supercomputers installed in 2022, ran side-by-side existing hurricane models last year. It is expected to supplant current forecast models by the end of the 2024 hurricane season.

2024 hurricane season: New 'cone' means upgrade to tracking forecasts

“This may be an opening to break the barrier in track forecasting,” said Vijay Tallapragada, senior scientist for NOAA’s Environmental Modeling Center, about HAFS. “Tracking has been stagnated for a long time. This is expected to increase forecast skill by 5 to 10%.”

The Mean Season: Two decades later, 2004 is remembered as the 'mean season' as hurricanes shredded Florida

Between 1990 and 2015, track errors were reduced by 70%, Cangialosi said.

The reasons for that kind of long-term improvement are many.

Pieces of code that go into computer models representing characteristics of the atmosphere, such as temperature, moisture and winds, have gotten better. Computers are running at higher resolutions. And more sophisticated satellites circle the Earth beaming down images so clear, forecasters see towering cloud tops and fields of Saharan dust like never before.

"One thing we are trying to figure out is is this a temporary pause in improvements until we get a next wave of technology or is it something more severe," Cangialosi said about the plateau in track forecasts. "My hunch is it's more temporary."

The size of the hurricane forecast cone is adjusted each year before June 1 based on the error rates of the previous five seasons, so this year's cone builds on forecasts made between 2019 and 2023. The cone, which covers days 1 through 5 of a forecast, is made up of circles sized so that 66% of the time the center of the storm has stayed inside that area.

2024 Hurricane season: NOAA makes highest storm forecast on record. What are chances SoFla impacted?

2024 hurricane season: Uncertainty outside the 'cone' still a concern

A smaller forecast track cone means less uncertainty on where a tropical cyclone is headed but notably does not forecast impacts outside of the cone, such as storm surge, flooding rains and damaging winds that can occur in surrounding areas.

The average three-day NHC track forecast error for Hurricane Floyd in 1999 was 236 nautical miles.

That's down to 102 nautical miles in the cone the NHC will use this season. Still, that’s slightly bigger than compared to 2023.

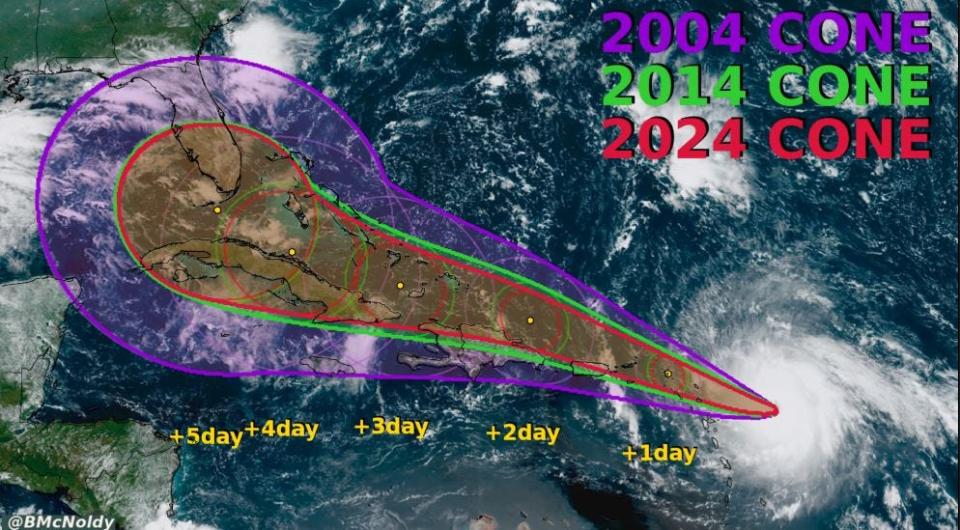

“This year, the cone is actually larger at all lead times compared to recent years,” said Brian McNoldy, a senior research associate at UM's Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric and Earth Science, in his Tropical Atlantic Update blog. “At a one-day lead time it's the biggest it's been since 2020, at two days it's the biggest since 2018, and at five days, it's the biggest since 2016.”

In the past decade, forecast track errors at five days out improved a scant six nautical miles from 226 nautical miles to this season’s 220.

Is our time up?: Why hasn’t Palm Beach County been hit by a massive storm lately? Well, it ain’t science

One storm that dinged track forecast accuracy last year was the mostly unknown Tropical Storm Philippe, whose lazy meander west of the Leeward Islands was tracked for 14 days by the NHC beginning in late September.

Unrelenting wind shear but incredibly warm water warred with each other on whether to shred the storm to bits or build it up to hurricane status. Philippe acted erratically in slack steering winds, turning north, stalling, drifting south, and then drenching Barbuda before pushing out to sea.

Track errors in some cases were more than double the five-year mean and increased seasonal track errors up to 25%.

“There is room to run, we just need more technology,” Cangialosi said. “And that’s primarily advancements in the weather models.”

Register for the Palm Beach Post's 2024 Storm Season Preparation forum

The 2024 hurricane season is forecast to be one of the most active on record with most predictions calling for more than 20 named storms. To help our communities get prepared, The Palm Beach Post is hosting a forum on storm readiness Wednesday, June 5, from 6:15 to 8:30 p.m. at Palm Beach State College's Lake Worth Beach campus. To attend, please scan the QR Code to register or click this link.

Kimberly Miller is a journalist for The Palm Beach Post, part of the USA Today Network of Florida. She covers real estate and how growth affects South Florida's environment. Subscribe to The Dirt for a weekly real estate roundup. If you have news tips, please send them to [email protected]. Help support our local journalism, subscribe today.

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: Has cone of uncertainty reached its limit in predicting storm track?