Hundreds of day cares are closed today as educators go on strike. Here's why

Hundreds of child care providers in 27 states and Washington, D.C., went on strike Monday to remind policymakers how essential they are, not only to families but to the nation’s economy.

Early childhood professionals – and the parents they serve – said they’re fed up with the lack of progress on policy promises such as better wages and expanded subsidies.

“I’ve never met a family who has said child care is affordable,” said Allyx Schiavone, a member of the Ideal Learning Roundtable, a national group of developmental early childhood education experts. Schiavone helped organize a Connecticut-specific day of activism this year.

Few providers make much of a profit, and many are in the red: Teaching and caring for young children is as expensive as it is essential.

Center closures were among various ways organizers took action Monday as part of "A Day Without Child Care: A National Day of Action." Some will take students (and any interested parents) on field trips to rally at state capitols or city halls or to celebrations at parks. Others simply asked parents to wear to work pins with statements such as "I wouldn't be here today without child care."

There were more than 50 confirmed events and nearly 400 providers who pledged to call out, close their doors or strike Monday, according to Wendoly Marte, a community organizer in New York City who helped coordinate the national initiative.

'Why should I have to sacrifice taking care of my family?'

Demand for child care far exceeds the supply, and one reason is a staffing crisis. There are few incentives to work in early learning: The jobs tend to pay poverty-level wages and lack fringe benefits.

A survey conducted last summer found that 4 in 5 early learning and care centers nationally were understaffed, according to the National Association for the Education of Young Children. Providers participating in the day of action said the problem has gotten worse, pushing some of their workers to lower-stress, higher-paying jobs at warehouses and chain restaurants.

A 'confusing and frustrating maze': COVID-19 made finding child care even harder

Before COVID-19, Shineal Hunter's Family Circle Academy in Philadelphia served 65 children. Now, Hunter has only three teachers, so she's down to about two dozen kids.

In consultation with staff and parents, she decided to close down her center Monday to make a statement as a Black woman and fourth-generation child care provider.

"Enough with the talking. ... Why should I have to sacrifice taking care of my family? Why am I constantly in a position where I have to choose?" Hunter said. "I want to leave my business to my children, but I'm strongly against advocating for my daughters coming into this industry."

Hunter's event will start with a rally at City Hall, followed by a block party in the center's neighborhood.

Many of the women spearheading protests were themselves mothers who relied on – and struggled to afford – child care when their kids were younger. They paid their dues and got their degrees, studying early childhood education, working in classrooms and complying with all the licensing rules to retain their designation as high-quality.

Women account for almost all of the child care workforce, and a disproportionate number are women of color. Their median wage is $13.22 an hour.

Parents desperately need child care: But day cares struggle to retain workers.

Despite her passion for the work, Kelly Dawn Jones is similarly skeptical about passing down her child care business to her children. Jones, a single mother, runs a child care center out of her one-bedroom home in Indianapolis. Love Your Child's Care Childcare serves about a dozen children for 10 hours every weekday of the year.

Home-based providers are often subject to the same licensing requirements as centers, such as meeting teacher-student ratios. But they tend to face more barriers in accessing subsidies and are often paid less per child. That means Jones, who refuses to raise tuition for her largely low-income families, is barely getting by.

Jones’ children share a bunk bed in the bedroom, and she sleeps in the living room. She said she isn’t able to save for retirement and she’s had to put off dental work. She has no idea how she’ll pay for her aspiring-rocket-scientist son’s college education.

“The money isn’t being put where their mouth is,” Jones said. “The goal of this action is to hopefully snap people awake. Many providers and I really believed that when the pandemic occurred that everyone kind of got it – yeah, this thing is essential."

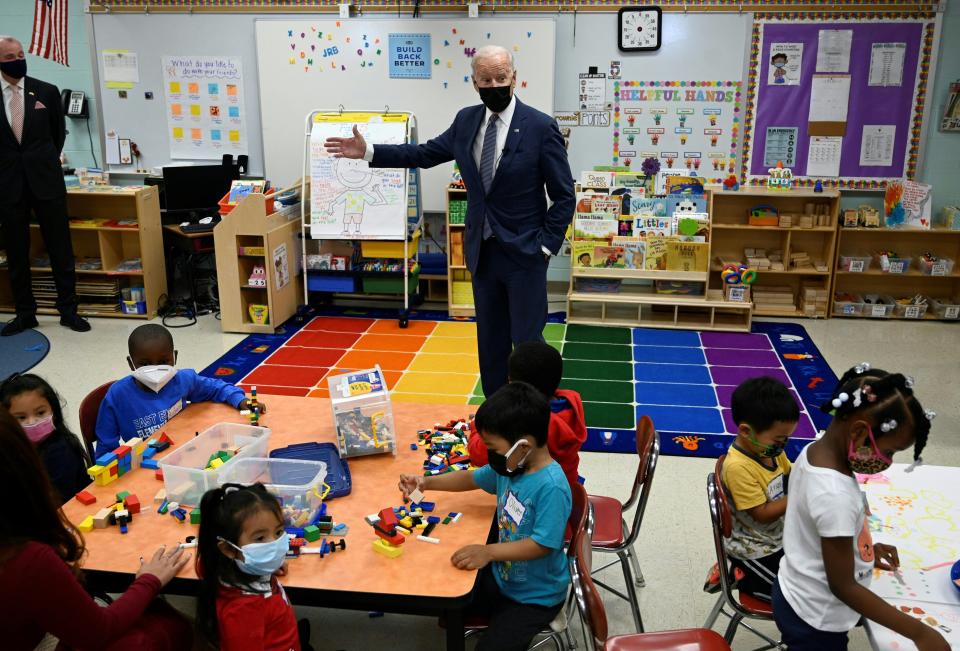

Failure of Build Back Better, other bills

At first, observers were hopeful as politicians on both sides of the aisle championed the need to invest in child care during the pandemic, said Marte, the national coordinator. After the failure of the Biden administration's Build Back Better domestic spending plan, which included provisions that would've set a cap on the amount families pay for child care and established minimum salary requirements ensuring pay parity for workers, that optimism quickly subsided.

Advocates have grown more demoralized by Congress' failure to continue an expanded child tax credit, which deposited monthly payments into parents' bank accounts. Democrats are pushing to renew the credit.

In some places, parent groups organized the Day Without Child Care events.

"The parent-provider relationship is one of the most symbiotic relationships in the world," said Oriana Powell, a parent organizer in Detroit. "The trajectory of my life has been decided by having to take care of folks" – from her child to her mother to her sister and, after her sister died, her sister's child.

Congress let COVID-19 relief expire: Millions of kids have fallen into poverty.

Powell will always remember a moment of clarity she had before her daughter, who's in pre-K, had reliable care. Her employer allowed Powell to bring her daughter into the office and work events. Her daughter grew accustomed to being around other people; she was beloved among Powell’s colleagues.

One day, Powell was giving a speech and realized she couldn’t see her daughter in the sea of her colleagues. Then, she heard a scream. Her daughter had fallen down the stairs. Fortunately, another woman picked her up almost immediately. It was the scariest moment of her life, and it taught her "I cannot be a worker and a parent at the same time."

"Providers show up because they understand that mothers have to work," Powell said. "And mothers know they have to work because they're invested in their child. There's no me without you."

Contact Alia Wong at 202-507-2256 or [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter at @aliaemily.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: A day without child care? Providers across the US are going on strike