A historic housing crisis has America in its grip. Can Marcia Fudge save the day?

WASHINGTON _ It was around dusk when about 15 of Marcia Fudge’s sorority sisters gathered on the deck of a friend’s house in Warrensville Heights, Ohio.

It had been a tough day. They had attended the funeral of U.S. Rep. Stephanie Tubbs Jones, a fellow member of Delta Sigma Theta. Fudge, a close friend and former chief of staff for Tubbs Jones, told them that August day in 2008 that some power brokers had urged her to run for the congressional seat.

She thought maybe she could protect the legacy of Tubbs Jones.

Fudge had been mayor in Warrensville Heights, a city of fewer than 14,000 people. A congressional campaign would require a huge war chest.

“We started collecting money right there. We said, ‘Oh, you got some money,’’ recalled Pamela Smith, a Delta and longtime friend.

Smith said she and others had no doubt Fudge, who was the first in her family to go to college, became a lawyer, served as national president of their sorority and had worked on Capitol Hill, was up for the job. Fudge would go on to be elected eight times as a Democrat for the 11th congressional district in Ohio.

On Wednesday, the Senate confirmed Fudge as secretary of the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development. Fudge received strong bipartisan support in a 66-34 vote, becoming the second Black woman to serve in the post and one of the most powerful government leaders in the nation, heading an agency facing the worst housing crisis since the Great Depression

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell voted in favor of Fudge, saying that "the nation needs the president to be able to stand up a team so long as their nominees are qualified and mainstream."

But critics cited her lack of experience on housing policies and what might be a steep learning curve. Fudge inherits a department with fewer people and funding than her predecessor, Ben Carson, as 40 million Americans face the threat of eviction.

Fudge’s supporters said her deep community ties, modest upbringing and life’s work as chief of staff, mayor and congresswoman, have prepared her for the role.

Fudge declined to be interviewed for this story, but nearly two dozen friends, colleagues, sorority sisters, advocates and high school classmates describe a woman who is passionate about helping the voiceless, opening doors for others and fighting to end poverty and hunger.

“She'll be on fire about trying to do the right thing,’’ said Peter Lawson Jones, a former high school classmate and longtime Ohio politician. “There's nothing flamboyant about her. She's solid. She's got a lot of integrity. And I think that the constituents of HUD will find that they have a champion that's on their side.”

Fudge's career guided by faith

Fudge, 68, grew up in Cleveland and later moved about 10 miles to Shaker Heights.

Faith was central in her upbringing and she says in everything she still does. She grew up in a home where she went to church every Sunday. Her mother and grandmother would attend in a full ensemble of matching hats, dresses and coats.

“I'm the kid that sang in the choir. I can't sing, cannot carry a tune in a bucket, but that's what we did,’’ Fudge recalled in an earlier interview with USA TODAY. “We were in the choir and we gave speeches …There was morning service, afternoon service, Bible school. I'm that kid.’’

Fudge, who is Baptist, said her faith teaches that she has the responsibility to give back.

“I'm doing the work that God has planned for me to do,’’ she said. “And I'm good with it.”

Also central to her life is her close ties with her family. Fudge, who is single and has no children, has two nephews, one grandniece and one grandnephew. She was one of two children, but her only brother was fatally shot when she was in college.

During her virtual confirmation hearing last month, Fudge turned to introduce her family, including her 89-year-year-old mother, Marian L. Garth Saffold, who was seated behind her in a room at Cuyahoga Community College in Ohio.

Fudge was raised by her mother, a labor organizer, and her grandmother, a domestic worker. She said neither had formal education outside of high school, but they pressed upon her the importance of education and a strong work ethic. She described them as “very, very strong Black women.”

“None of their lives were easy, but they always made us believe that we could be what we wanted to be,” said Fudge. “I just wanted to make them proud. I think that that's probably the thing that drives me most.’’

Fudge embraces Ohio roots

Fudge’s life is steeped in her upbringing. She still eats fried baloney, still plays bid whist, a popular card game among African Americans, still puts ribs on the grill and still shows up at the block party in Warrensville Heights.

She was the first woman and first Black person elected mayor of the predominantly African American city, located just outside of Cleveland.

She still has a home there. She also has a home in Washington, D.C., where she stays when Congress is in session, according to House financial disclosure reports.

Jones, a classmate of Fudge’s at Shaker Heights High School, remembered her as a star athlete, particularly on the basketball court. She also played on other teams, including fencing, field hockey and volleyball.

“She seemed to have a certain degree of confidence,’’ said Jones, 68, a former Ohio state representative and Shaker Heights councilman turned actor. “There was just an air about her of calmness. And you didn't hear her name associated with any silliness or foolishness … That wasn't Marcia. And she had enjoyed great relations with both the Black and the white students.”

Shaker Heights had a hard-fought history of integration dating back through the 1950s. Although white and Black neighbors in some areas worked to make it a part of their community, Mark Souther, an urban historian at Cleveland State University, said "the community as a whole remained resistant to the idea of integration until perhaps the later 1960s."

Today, Shaker Heights is home to a population that is 56% white and 35% Black, according to the Census.

Lee Fisher, who attended Shaker Heights two years ahead of Fudge, said she had a no-nonsense attitude.

"You just always knew she was destined to do something great," he said.

Their careers later overlapped when Fisher was Ohio’s lieutenant governor and Fudge was chief of staff to Tubbs Jones and later mayor of Warrensville Heights.

Fudge went to Ohio State University where she majored in business. She later attended the Cleveland-Marshall College of Law at Cleveland State University where she graduated in 1983.

In the mid 1990s, Jones and Fudge later shared their first law office space in Shaker Heights.

As Smith, her longtime friend, recalled, it was a small suite of rooms in a building on a main street. There was no big sign outside with Fudge’s name on it. And it was Smith, Fudge and their friend Marsha Brooks who put together the furniture, including the credenza. There wasn’t money for a carpenter.

“We were poor little Black girls, struggling, striving,” Smith, a retired educator, said with a laugh. “We got whatever we needed to get done, done. We just helped each other.”

Together they celebrated victories: earning degrees, buying their first homes, launching careers.

“To see someone who knew what she wanted to do, set herself a goal to be done with her law degree in x number of years, then to pass the bar ... It was fabulous,” said Smith.

A Black sisterhood provides community

It was at Ohio State where Fudge joined Delta Sigma Theta, one of the nation’s largest Black sororities. Later in 1979, she won a seat on the sorority’s national finance committee and two years later successfully ran to chair that committee.

Smith, who became her campaign manager, said Fudge had her sights on becoming an officer in the sorority. In 1996, she won her bid for national president and served four years.

“She was a straight shooter,’’ said Smith. “If you asked, she’d tell you.’’

Smith said Fudge steered the sorority back to its mission of scholarship and service.

Under her leadership, the sorority paid off the mortgage on its headquarters and adopted signature programs, including ones that provided mentoring and etiquette training for girls, said Smith.

The role also gave Fudge a national platform and connections to a network of tens of thousands of Black women. Fudge can often be spotted wearing the Delta’s signature crimson red and cream, such as during her Senate confirmation hearing.

When Sherrod Brown was running for the U.S. Senate in Ohio, he went to meet with Fudge, whom he called an influential mayor. She told him about her connections to Deltas across the state. He left clutching a list of names of sorority sisters.

In the years since, Brown, who is serving his third term in the Senate and lives in Fudge's district, has attended the Delta breakfast held in the U.S. Capitol.

“There were always these women from Ohio in red coats running around the Capitol,’’ he said.

Grooming the next generation of Black leaders

Fudge is known for hiring talented people and helping groom them, particularly young people. She’s mentored several on and off Capitol Hill who say she not only encouraged, but guided them.

Bradley Sellers was three months into retirement from the NBA and swinging golf clubs every day when he was summoned to meet with Fudge, then the mayor of Warrensville Heights. He went to her first-floor office assuming she wanted help with a sports project or something.

But in an office with the door closed, Fudge told Sellers, a Warrensville Heights native, he needed to run the city’s economic development program. The salary was nowhere near what the former Chicago Bulls player was used to nor a job on his bucket list. Still, he listened to the woman he just met and decided later to do it — for a year or two.

“She saw something in me that I probably didn't see in myself at the time. She saw a skill set because she does her homework,’’ said Sellers, who majored in economics at Ohio State University.

Sellers stayed in the job for 11 years. When Fudge decided to run for Congress, she urged him to run for mayor.

“She was like, ‘OK, I'm going to Congress and the seat won't come open for another two and a half years, but I groomed you for this,’’ Sellers recalled her telling him. “I've shown you everything. You understand the mission. I'm going to need you to carry this forward because we put too much time into building this back.’’

Sellers is headed into his 10th year as mayor.

Basheer Jones didn’t care much for politics. Then he met Fudge, who was a guest on his radio show in Cleveland 15 years ago. She told him there’s a difference between being an elected official and a public servant. “It rocked me,’’ he said.

Fudge took Jones, 36, under her wing, offering advice—personal and political, helping raise money for campaigns and making calls to get support.

She constantly reminded him, “If you do right by the people, the people will do right by you.’’

Fudge was the only person who endorsed him in 2013 in his first bid for the Cleveland City Council over the Democratic incumbent. He lost by 600 votes. She encouraged him to run again four years later.

“She made me run. Mothers don’t encourage. They say ‘Boy!’ She made me run and I ran,’’ Jones said with a laugh. He won by 13 votes. This year he’s running for mayor.

He credits Fudge with being his political mother.

“She said, ‘I got your back,’’ he said. “And she never left me.”

Fudge carved her own path in Congress

South Carolina Rep. James Clyburn, the House majority whip, got a call from Fudge’s stepfather in 2008 asking him to support her bid to fill Tubb Jones’ congressional seat.

“I told them I would do what I could,’’ Clyburn recalled.

Fudge won that special election and later the general election.

Five years later, she was elected chairwoman of the Congressional Black Caucus, a powerful bloc of mostly Democrats.

And in 2018, she threatened to challenge Nancy Pelosi for her spot as speaker of the House. Fudge got a subcommittee chairmanship out of it.

She served on the Agriculture, Education and Labor and the House Administration committees, where she championed expanding access to food nutrition, addressing education disparities and protecting voting rights.

Last year, Fudge pushed to include a measure in a COVID-19 relief bill that allows students eligible for free or reduced lunch to have meals through SNAP while attending school online. One in four constituents in her district live below poverty.

"She's a pragmatist," said John Corlett, president and executive director of The Center for Community Solutions, a nonpartisan think tank focused on economic issues in Ohio. "I've seen her less as someone tilting at windmills and more on trying to move things forward."

Fudge also chairs an agriculture subcommittee and one on elections, where she has focused on voter suppression.

Illinois Rep. Rodney Davis, the top Republican on the election subcommittee, has worked with Fudge on both committees. He called her a tough competitor.

“I raised some eyebrows by voting with Marcia on some of her nutrition-related amendments,’’ said Davis. “And we developed a relationship there that was very cordial. That didn't always remain when she decided to come over to House Administration and take over as the chair of the election subcommittee. But I think there's mutual respect even when we have some differences.”

Davis supported her for HUD secretary.

“To know that I can pick up the phone and call the secretary if there's a major issue in my district, I think is a benefit regardless of what party the administration is made up of,’’ he said.

A leader for other lawmakers

Ohio Rep. Joyce Beatty remembers as a freshman, Fudge, then chair of the Congressional Black Caucus, invited her and other new Black lawmakers to dinner one evening and told them to bring family. Fudge said it was important for their families to understand the life of a member of Congress.

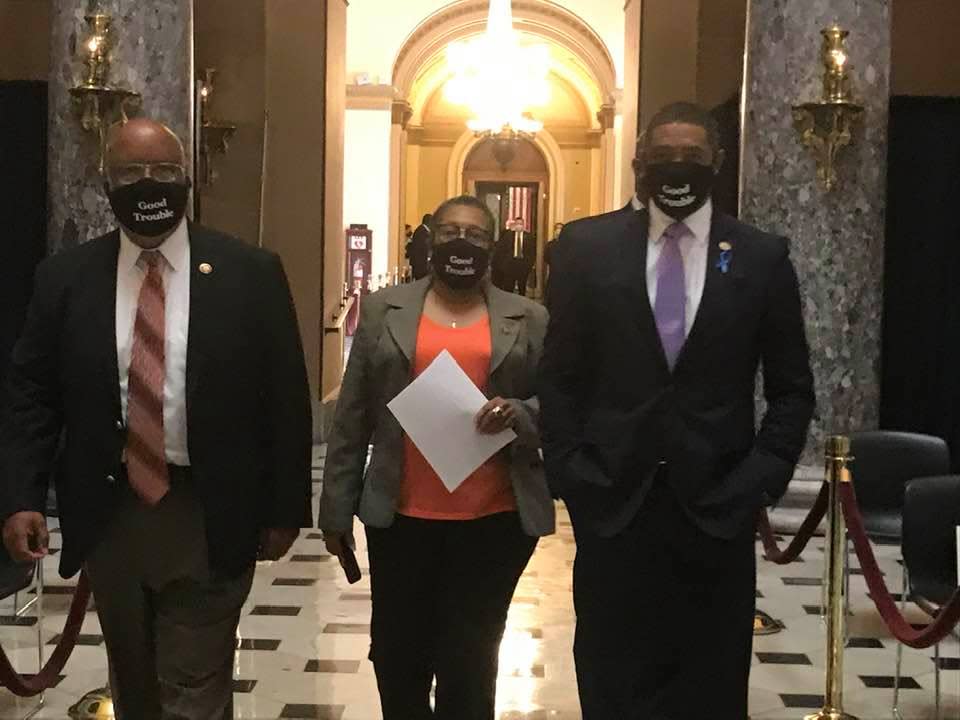

They gathered in a private room on Capitol Hill. Fudge took a seat in the middle of a long table.

“She didn’t come in as most leaders do and sit at the head of the table,’’ recalled Beatty. “She sat in the middle and she said, ‘I will always be with you whether she was leading us or not.”

The freshmen peppered Fudge with questions. She explained protocols, committee assignments and suggested places to live. She also urged them to work across the aisle.

“If you wanted to get legislation done … you cannot do it in isolation,’’ Beatty recalled Fudge sharing.

The support didn’t stop there.

Seats in the House chamber are not assigned, but Beatty said Fudge would take her usual seat off the aisle up front near the voting box. She invited Beatty to sit next to her so she could school her on the ways of Congress. It was there that Beatty said she marveled at Republicans coming over to Fudge to seek advice.

“Everybody knew where Marcia sat on the House floor,’’ Beatty said. “So to be able to sit as I call it, ‘Second chair to the boss lady' was huge.”

Sen. Cory Booker, a Democrat from New Jersey, said Fudge was like a sister to him when he was elected in 2013. At the time, he was the only African American Democrat in the chamber.

“She really helped me deepen my relationship and friendships with the Congressional Black Caucus and helped me see that this was really my family in Washington and really my allies in getting good things done,’’ he said.

Booker said Fudge included him in the caucus push for criminal justice reform and credits her with working behind the scene to get momentum to pass a measure.

“She knows how to make the sausage,’’ he said.

Booker sought her advice in 2019 when he considered running for president.

Fudge was also the only member of Congress to threaten his life after he brought vegan food to a caucus meeting.

“She teased me that my time in the world might be shorter if I brought Black folks in the caucus vegan food ever again,’’ he said with a laugh.

Nations faces historic housing crisis

The Department of Housing and Urban Development was created in 1965 and was supposed to help low-income Americans enter the housing market after decades of redlining and predatory financing practices by the federal government and private lenders had locked out Black and brown families.

Fudge would start with a budget of $47.9 billion, a 15% drop from last year.

"It's a disastrous time to be learning on the job," said James DeFilippis, a public policy professor at Rutgers University in New Jersey.

Bill Faith, executive director of the Coalition on Homelessness and Housing in Ohio, who worked with Fudge on housing measures, said HUD has been hollowed out.

“Bringing in good people will be important to rebuild that agency,” he said.

Fudge has been doing homework, including reading, "The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America'' by Richard Rothstein.

Fudge told lawmakers at her confirmation hearing that 21 million Americans pay more than 30% of their income on housing and conditions were dire before the pandemic.

"On any given in 2019, more that 500,000 people experienced homelessness in America," Fudge told senators. "That's a devastating statistic."

She vowed to work with Republicans and Democrats to among other things, expand housing programs. Only one in five eligible households receive housing assistance, she said.

"Much like COVID-19, the housing crisis isn't isolated by geography, people in blue states and red states, in cities and towns," she said.

She also pledged to tackle racial disparities in homeownership. The rate of Black homeownership had not improved from 41% since 1968, when the Fair Housing Act was enacted.

“I will do everything in my power to ensure every American has a roof over their head,” said Fudge.

Not everyone appreciates what Fudge has to say.

Some critics have railed against her for writing a 2015 letter on behalf of former judge Lance Mason in a domestic violence case. Years later, he was sentenced to death for killing his wife. In a statement then, she condemned the crime and said her support for Mason had been based on the man she had known for years.

Others have accused her of being too partisan.

During her confirmation hearing, Pennsylvania Sen. Patrick Toomey, the top Republican on the committee, questioned Fudge about comments she made last September. Fudge described Republicans who wanted to quickly fill the seat of the late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Ginsberg as having no decency, no honor and no integrity.

Fudge answered that she has a reputation for bipartisanship.

“I do listen to my constituents and sometimes I am a little passionate about things. Is my tone pitch-perfect all the time? It is not,’’ she said. “But I do know this. That I have the ability and the capacity to work with Republicans and I intend to do just that.”

GOP Sen. John Kennedy from Louisiana called out Fudge for saying Republicans don’t care about people of color, even a little bit.

“Do you think Republicans care about people of color?”

“I do some, yes,’’ Fudge responded.

“Do you think most Republicans care about people of color?’’ Kennedy asked.

“Yes, I do,” Fudge said.

Toomey was among the seven Republicans on the committee to vote against her nomination.

A close relationship with local mayors

Fudge supporters initially lobbied for her to head the Department of Agriculture.

Clyburn, who led the push, said it was important to have someone like Fudge who would advocate for nutrition programs, rural development and owners of small farms.

“I wanted somebody in that office who would be there for little farmers; be there for the other end of the spectrum,’’ he said. “She had the background and experience and the sensitivity that is necessary to do that.”

Instead, Biden nominated Tom Vilsack, who led the Agriculture agency under the Obama administration.

Brown, the senator from Ohio, had also pushed for Fudge to head the Ag agency, but as the new chairman of the Banking, Housing and Affairs Committee, he said housing will be a priority and he will work closely with Fudge.

“We do so poorly on housing in this country. That’s why I’m excited about her being there,’’ he said. “I like the idea of her being in the room with President Biden at these cabinet meetings.’’

Mayor Nan Whaley, a Democrat representing Dayton, Ohio, said Fudge’s experience as a mayor will help her succeed because she knows what local officials need.

“She just has a natural affinity I think for a lot of mayors because that's kind of how we feel too—like we have to speak up and advocate and fight on behalf of the communities that a lot of time don't get a voice,’’ Whaley said.

'A silent killer' against the competition

It’s at the card table where many say Fudge has also beat her rivals — friends and family included. Her determination to win hints at how she might run HUD during this moment of widespread need.

Some victories have come with Clyburn, her regular bid whist partner. They often play with other Black lawmakers late into the night after Congressional Black Caucus events.

“We don't lose,’’ he said.

Clyburn remembers one night years ago sitting down to play at 8:30 p.m. and not ending until after midnight.

“You can tell a whole lot about a person by playing golf with them. That's how I get to know most men,’’ said Clyburn. “And if you sit down and have a card partner you can tell a whole lot about a person by the way they play cards.”

Challengers say Fudge will smile and talk trash, but take no prisoners as Jones, her high school classmate, found out a few years ago.

“She's a silent killer on the bid whist table,’’ he said.

Bid whist, popular in African American culture, is a game of strategy, teamwork and looking ahead. It’s often played by fierce competitors. There’s a lot of bluffing. One key skill is to be able to read your opponent.

Those skills will give her an edge as the new HUD chief, her supporters say.

“She thinks far ahead,’’ said Clyburn. “She's very good. And she thinks she's better at cards than I am.”

Follow USA TODAY national correspondents @dberrygannett and @RominaAdi

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Biden's cabinet: Marcia Fudge confronts crisis as new HUD Secretary