Grimes Tried to Make a Soundtrack for the End of the World. The Result Is Surprisingly Timid

This is how the human race ends: with the shallow clang of metal on metal, a squalling screech, the heavy stomp and throb of percussion. At least, that’s how the A.I. revolution goes down in “We Appreciate Power,” an arresting single by Canadian art-pop eminence Grimes with help from frequent collaborator HANA. Surprising contrasts are a trademark of Grimes’ songwriting and production, and on this track she cuts the harshness of the beat with vocals that whisper, coo and cajole despite the cartoon militancy of lyrics that demand: “What will it take to make you capitulate?” It’s a crazy song, stuffed with musical ideas, inspired by Kim Jong-un’s reportedly handpicked, all-female North Korean pop band Moranbong and written in the voice of what a press release described as “a Pro-A.I. Girl Group Propaganda machine” evangelizing for their robot overlords.

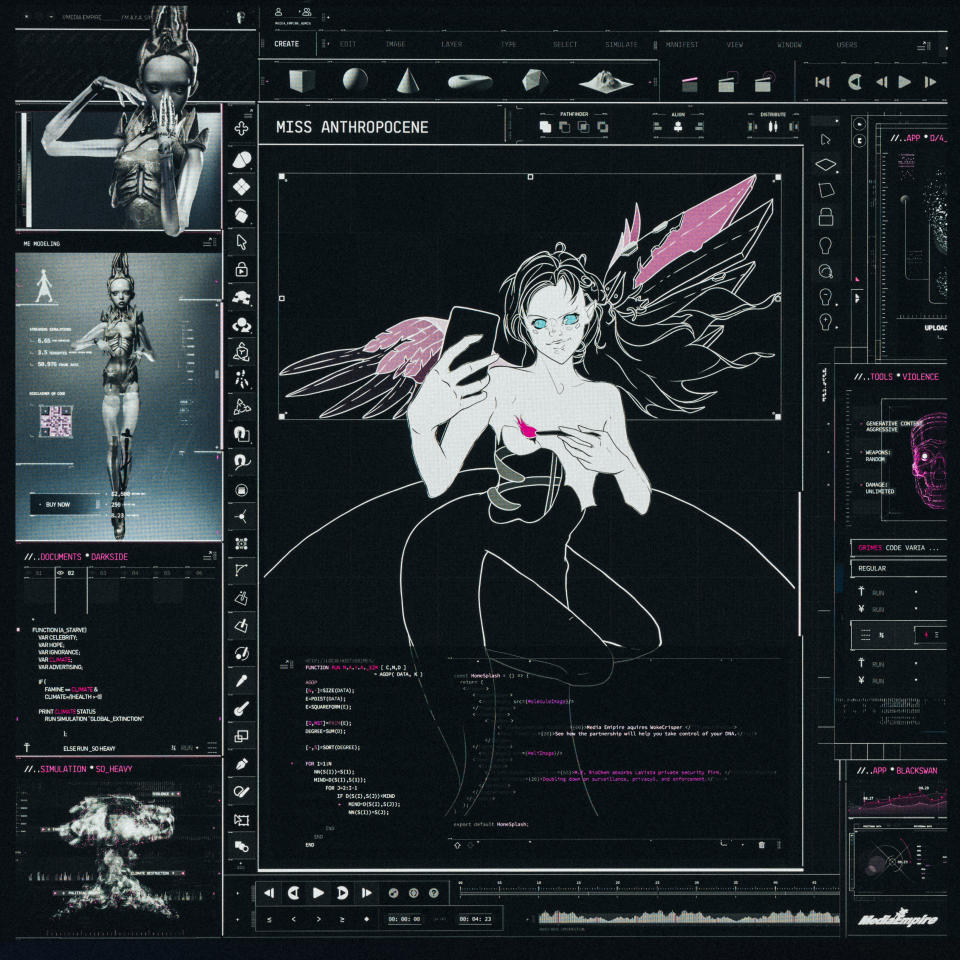

Released in November 2018, “We Appreciate Power” was supposed to be an early cut from Grimes’ fifth album, Miss Anthropocene, which is named for the grim current geological era. Though the record was delayed for more than a year before finally dropping on Feb. 21, Grimes—the stage name of 31-year-old Claire Boucher, who now apparently goes by “c,” as in the scientific constant for the speed of light—has attracted more mainstream attention than ever in the interval, and not just because she’s kept the one-off singles and collaborations flowing. Ever since she attended the 2018 Met Gala on the arm of divisive PayPal/Tesla/SpaceX billionaire Elon Musk, she has been at the center of a media whirlwind, her every interview and tweet subject to widespread scrutiny. Even during her rise to the highest echelons of indie-music fame in the mid-2010s, she had a tendency to wind up in the middle of controversies. And now she’s half of an easy-to-mock pop-culture power couple, her identity as a musician often erased by headlines that identify her solely as Musk’s girlfriend. It’s a familiar narrative for women artists. But the fact that her newfound celebrity has begun to overshadow her work as a singer, songwriter and producer is especially frustrating for those of us who see her as a rare talent—an artist whose indelible melodies and off-kilter perspective come together to make sublime, occasionally maddening but always singular, music.

Take “We Appreciate Power,” one of the weirdest singles in a career defined by them. I’ve had the earworm chorus stuck in my head on and off for the past 15 months, which is extra unsettling when you consider that the singer isn’t necessarily opposed to authoritarian rule by artificial intelligence. “Everyone’s so worried about the evil A.I. wiping us out,” she mused in a 2019 interview. “I think the A.I. will be cool.” Eerie though it inarguably is, far-out beliefs like this one have helped to make Grimes one of music’s most distinctive voices. Her forward-thinking compositions are inseparable from her idiosyncratic cluster of obsessions: technology, sci-fi and fantasy, K-pop, video games, international cinema, ancient societies. Even more than Gen Z stars like Billie Eilish and Lil Nas X, her identity seems forged in the fires of internet culture, where there’s a fandom for every obscure interest and a forum for even the most outlandish points of view. Which is why it’s unfortunate that “We Appreciate Power” didn’t end up in the unexpectedly timid Miss Anthropocene after all.

It’s possible that, arriving more than four years after the release of 2015’s Art Angels and preceded by five singles out of just 10 total tracks, the album itself was always going to feel overworked and anticlimactic, less a rejoinder to nonstop Grimes Discourse than a casualty of it. Grimes fueled anticipation with grand descriptions of Miss Anthropocene as a concept record named for an imaginary “death god” meant to personify climate change, on which every song would offer a different vision of death. She seemed to want to push buttons, claiming that she hoped to render environmental apocalypse thinkable by removing guilt from the public discourse around it—by making something “beautiful” and “fun” that would tackle humanity’s impending doom, in the form of “an evil album about how great climate change is.” If you’re looking, you can detect traces of this bold, almost trollish conceit in both the lyrics and sounds as diverse as the glitchy industrial rock that briefly dominated alternative radio in the late ’90s and the swirling rhythms of Bollywood, as if in a final retrospective of human dance music. But if you’re not, you probably won’t find it.

To be clear, Miss Anthropocene is by no means a bad album. Several individual tracks are quite good. Like a Red-era Taylor Swift jam, “Delete Forever” opens with disarmingly spare strumming and maintains a subtle country jangle throughout its four minutes. Grimes’ often-otherworldly vocals are plaintive, almost conversational, tethered to earth; she has said that “the finished product is basically almost the demo.” It’s a fittingly somber treatment for a song about the opioid crisis, written just after she learned that the influential 21-year-old rapper Lil Peep had died of an overdose. The few adornments—a churning loop, horn sounds that join the mix in a long outro—gorgeously offset the simplicity that surrounds them. The low-key devastating refrain, “I see everything,” rides in for the first time on a shooting star of twinkling sonic sparkle.

Another highlight, “4ÆM” is about as eclectic—and giddily chaotic—as the record gets. Grimes feeds a sample of “Deewani Mastani” from the Indian blockbuster Bajirao Mastani into a tornado of harsh dance beats and layered, chattering vocals. Its retro-futuristic vibe should fit right in on Cyberpunk 2077, an upcoming sci-fi video game on which she also voices a character. Yet the sugary hook that creeps in two-thirds of the way through, along with its viscerally slap-happy evocation of insomnia, ensure that the song does more than provide an appropriate soundtrack for mashing buttons.

Miss Anthropocene also reflects Grimes’ impressive evolution as a producer; by now she could bend and meld genres into breathtaking new shapes in her sleep. But not even the highlights stand up to Grimes’ most memorable singles, from the vivid, vicious dance-pop of Art Angels’ “Kill V. Maim” and “Flesh Without Blood” to the anxious, Tiffany-on-uppers frenzy of “Oblivion” from her breakthrough third album, 2012’s Visions. What’s more frustrating is that the songs don’t hang together as tightly as a concept record with the ambitious and mischievous goal of wringing aesthetic beauty out of the death of our planet should.

Grimes’ lyrics have always been elliptical, which isn’t necessarily a problem unless you’ve promised to conjure a fully immersive allegory. The gulf between what she described in a conversation about “New Gods” as the “sick” contemporary idols of “plastic and pollution and plastic surgery and social media” and that icy power ballad’s vague laments—“Hands reaching out for new gods/You can’t give me what I want”—is too wide for listeners to fill in. Album opener “So Heavy I Fell Through the Earth” prettily showers trip-hop beats in New Age glisten, but its central image of overwhelming sexual love is generic. Unlike the menacing girl group of “We Appreciate Power” or the antiheroes of other concept albums (Ziggy Stardust, Grimes collaborator Janelle Monáe‘s ArchAndroid alter ego Cindi Mayweather), Miss Anthropocene never coalesces as a character.

As a result, the album lacks the audacity of Grimes’ interviews about the album. If she is indeed feeling cautious about what she expresses in her music these days, it’s hard to blame her. Musk’s quick temper, futurist bluster and various business gaffes have made him—and, by association, her—a popular target of disdain and ridicule, particularly by the skeptical, left-leaning indie subculture that made up much of Grimes’ original fan base. She’s felt compelled to respond to accusations that Musk is a union buster and been drawn into his legal dramas, his disastrous Cybertruck rollout, and even an odd saga in which pugnacious rapper Azealia Banks visited his home. Grimes’ glib, inflammatory yet also fascinating prediction that A.I. would not only conquer humanity, but also eclipse our artistic abilities fueled weeks of heated debate. Now she’s pregnant and Musk is presumably the father; she broke the news by posting to Twitter topless photos in which a fetus is visible beneath her translucent skin.

Watching her weather these news cycles, I couldn’t help but think of Lena Dunham—a onetime feminist indie-film darling whose mainstream breakthrough, HBO’s Girls, exposed the limitations of her privileged worldview and made her a punching bag for detractors of all ideologies. In both cases, the critiques of these women are often valid, but the intensity of the backlash can feel disproportionately, gleefully nasty to an extent that suggests underlying misogyny. Such media narratives are so difficult to escape (if still perhaps enviable trade-offs for musicians who wouldn’t mind if a billionaire came around to liberate them from the music industry’s 21st-century monetization problems), they could make a musician want to sand down the most potentially controversial aspects of a record already primed to be pilloried. “On my last record I was like, ‘I don’t care. I’m not trying to impress anybody,’” Grimes told Lana Del Rey in a recent conversation for Interview. “And on my new record I’m trying to impress everyone.”

It’s not really for me to say whether Grimes deserves your sympathy or, for that matter, your scorn. But it seems like a side effect of all this noise that her new album that sounds like a pleasant, skillful, sometimes beguiling feint—a pulled punch from an artist whose superpower used to be her sonic and conceptual fearlessness. There’s a loneliness to the rarefied cultural space she and Dunham occupy, where money, power and fame insulate you from the financial blow of a failed project but can’t wrench control of your identity from a narrative you didn’t create. That isolation comes to define Miss Anthropocene, manifesting as restlessness, insomnia, darkness, desolation, want. The image that sums it up is Grimes in the “Delete Forever” video, posing listlessly in a crimson gown on a marble throne placed amid computer-generated Grecian ruins. As the shot widens, you can see Earth far away in the night sky but no signs of life on the ground. What suddenly matters more than whether this woman is Grimes or Claire or c or Miss Anthropocene is the sense that she is profoundly alone.