I Was George Floyd

Before I learned how to use my fists I withstood a few knuckles to my cheekbones. One time, a little boy smashed a large rock into my eye, leaving a gash so deep that it required stitches. All of it before Kindergarten. When I did begin school, I used violence to settle differences. It was soon decided that my behavior was abnormal. Before completing second grade I was taken out of the Columbus Public School system and sent to St. Vincent Children’s Center, a school that specializes in children with learning, behavioral, and psychological issues.

Mrs. Osborne, one of two Black teachers at St. Vincent was the first woman to make me feel loved. She told me I was brilliant, beautiful, and she bragged to her colleagues about my studiousness. Not only did I believe Mrs. Osborne, but I wanted to live up to what she saw in me. Mr. Johnson was my other favorite teacher. Like Mrs. Osborne, he praised my bookishness.

I do not recall excelling inside the classroom at St. Vincent. What I do remember is Mrs. Osborne’s love. I especially remember culturally relevant teachings of Mr. Johnson. I wanted to know who was the red-faced man inside the pendant hanging from Mr. Johnson’s neck? He taught me it was Malcolm X. He drove me to a Black-owned bookstore on Livingston Ave. and it filled me with wonder, which lived opposite my apprehension at hearing the big kids in my neighborhood talking about life inside T.I.C.O., a jail for juvenile felony offenders in Franklin County, Ohio. I would roam the bookstore thumbing through pages of books, wondering who were these important-looking Black people between the pages. I didn’t ask too many questions about books, but I did ask about the hip hop music he listened to. He played a lot of Ice Cube, A Tribe Called Quest, and Public Enemy. He would use hip hop to discuss social issues like drug abuse, crime, and the poverty that was prevalent in my neighborhood, as much as a 7-year-old could understand.

In the 5th grade, I left St. Vincent’s Children’s Center. I was back in the public school system, but in remedial classes. Here, I felt invisible, and disconnected from the teachers as well as the curriculum. My home life didn’t improve either. I was barely going to school, living in a group home, or in jail at Franklin County Juvenile Detention Center. I would go to jail for petty offenses. Once, I broke a guy’s window because he wouldn’t fight me. Another time, a friend and I were caught stealing basketball jerseys out of the mall. I eventually moved to Laurel, Mississippi with my grandmother, who, realistically, was too old to keep an eye on me. Shortly afterwards, I dropped out of school to become a full-time drug dealer. Another grownup I knew, who struggled with crack addiction, taught me the ins-and-outs of the drug game, watching over me while I hustled crack.

Decades before I became a full-time hustler, George Floyd was born in Fayetteville, N.C., eventually settling in Houston, TX. In many ways, our lives ran parallel. The education he received at Jack Yates High School failed him. Jacks Yates, a school known for its stellar football program and where Floyd was star athlete, suffered from decaying facilities, out-of-date textbooks and vestiges of segregation. According to Robert Samuels and Toluse Olorunnipa’s His Name is George Floyd: One Man’s Life and Struggle for Racial Justice, one Yates teacher even told Floyd that he’d receive a passing grade if he sat in the back of the classroom and didn’t talk.

Like many Blacks who do not receive culturally relevant education, Floyd saw his talents on the football field as a way to get his family out of poverty. While Floyd excelled on the basketball court and football field, he struggled inside the classroom. One teacher in particular, Bertha Dinkins, encouraged Floyd to think beyond Yates and sports. She saw in Floyd a smart kid, who struggled academically. But Dinkins encouragement contradicted what Floyd saw at Yates and in his neighborhood, Cuny Homes. The people who rose from poverty in Houston’s Third Ward did so because of their elite performances on the football field. A handful of Yates football players went on to the NFL. Few students even passed the standardized state tests needed to graduate high school. Floyd fell into this category, keeping him from graduating with his class.

Floyd is dead. I often wonder why I am alive today. Our stories diverged once I encountered a love of reading. Ironically, it took me dropping out of school to fall in love with books and words. Today, I am the Senior Culture Editor for this magazine, and a Justice-In-Education Scholar at Columbia University. No, my education and job title does not make me immune from racial violence, but they do place me in a position to show that I am George Floyd, and also show that all of the George Floyds of the world are actually human beings, with dreams of creating a new life for themselves. For me, change came through taking in the intellectuality of Nas, Wu-Tang Clan, Jay-Z, Jay Electronica, among others. These wordsmiths opened a flood of self-didacticism in me that I didn’t know existed.

While my former classmates graduated high school, enrolled into college, the army, or got a job at one of the chicken plants in Laurel, I graduated from hustling inside of crack houses to selling quarters and half ounces of crack. No longer was I hugging the block, making hand-to-hand sales. I was selling crack to the dope boys on the corner. With the violence, police harassment, my hyper-awareness of the drug game and feelings of hopelessness combined with the trauma lingering from my childhood, I began using cocaine.

But on the flipside, I became infatuated with the historical and social content found in hip hop and in hip hop magazines. Hip hop made me a voracious reader. RZA, of the Wu–Tang Clan, said his favorite books included The Good Earth, The Art of Peace, The Bible and the Holy Qur'an. Because RZA read these books, I wanted to read them, too. Nas rapped about the likes of Langston Hughes, Clarence 13X, and Huey P. Newton, among others. Because Nas rapped about them, I would buy books written by or about them. Hip Hop, and hip hop magazines, and the streets became my classroom.

Floyd’s shaky education kept him from realizing his dreams of playing Division 1 football. However, he still managed to receive a basketball scholarship to South Florida Community College. He continued to struggle academically. To stay eligible, Floyd had to take vocational classes such as welding and car repair. He eventually transferred to Texas A&M–Kingsville to play football. But many of the vocational credits from South Florida didn’t transfer, making him ill-prepared for basic subjects like math and English courses. He did so poorly inside the classroom, the school assigned him to remedial classes, making him ineligible to suit-up for football games.

Back in Cuny Homes, Floyd’s mother took on the responsibility of raising her daughter's children. The stress caused Floyd’s mother to develop high blood pressure and hypertension. She even had a stroke. As months passed at Kingsville, it became evident that Floyd would ever see action on the gridiron. Feeling dejected, still lacking education, and worried about his mother’s deteriorating health, he went back to Houston’s Third Ward, where he struggled to find a solid footing.

While Floyd bounced between brief jail stints for petty drug crimes and an aggravated robbery, I sensed my time in the streets was coming to an end. I was trafficking heroin from Louisville, KY back to Laurel and trafficking nearly 20 ounces of crack from Jasper County to Jones County, Mississippi every two weeks. But the lifestyle was wearing on me. On one trip to Louisville, tears pushed through my eyes. I wanted to create a new life, and I had an uncanny sense that I was about to go to prison, get murdered or seriously hurt, or harm someone in the act of protecting myself.

For months leading up to this particular trip, I’d been mulling over ways to get out of the drug game. I was in the process of creating a magazine, The Diary, where I would cover street culture and music in the Deep South. But after a couple of interviews, I realized that I didn’t know anything about writing feature stories. I tried to sell shirts and hoodies emblazoned with hip hop quotes, and quotes from the books I was reading. That didn’t work, either.

My feelings about death and prison were so potent that my grandmother told me she began having nightmares about my demise. Staring out of the window as Greyhound wrapped its body around the curves on Interstate-59, with tears falling, I dropped my head, feeling defeated. There, sitting in my lap, was Carter G. Woodson’s The Mis-Education of the Negro, a XXL magazine, and a notebook. You dummy, I thought to myself, you love hip hop magazines and history books. Go to college to study history and journalism.

A week or so later, I was arrested on Mississippi’s Interstate 59 with four ounces of heroin. At 21-years-old I was on my way to prison. I served nearly four years on a five year sentence.

A week before the anniversary of his death, I finished reading His Name is George Floyd. While reading, I could feel the sun rays beaming down on me while I stood on the corner with my hustling crew–the same sun rays that shed light on Floyd’s gleaming face as he lingered in Cuny Homes courtyards with his crew. I could see the uneven teeth of my friends as they laughed and joked and told stories about the night before. I could see the beads of sweat, ragged clothing, jaundiced-eyes, and stained-teeth of the addicts–addicts who we actually cared about—buying crack from us. I could see the serious stares, fresh clothes and detailed cars of the mid-level dope boys I did business with. I could hear the southern drawls–complete with wide eyes and huge smiles–of my friends saying how they’d one day not have to sell drugs for a living. Behind those smiles, if you looked closely, you could see the pain that comes with knowing that none of us had a promising future, as badly as we wanted one. His Name is George Floyd brought roaring back the conversations I have had with men who have shot and stabbed guys about their feelings of hopelessness and wishing their lives were different. I realized that I am no different than Floyd.

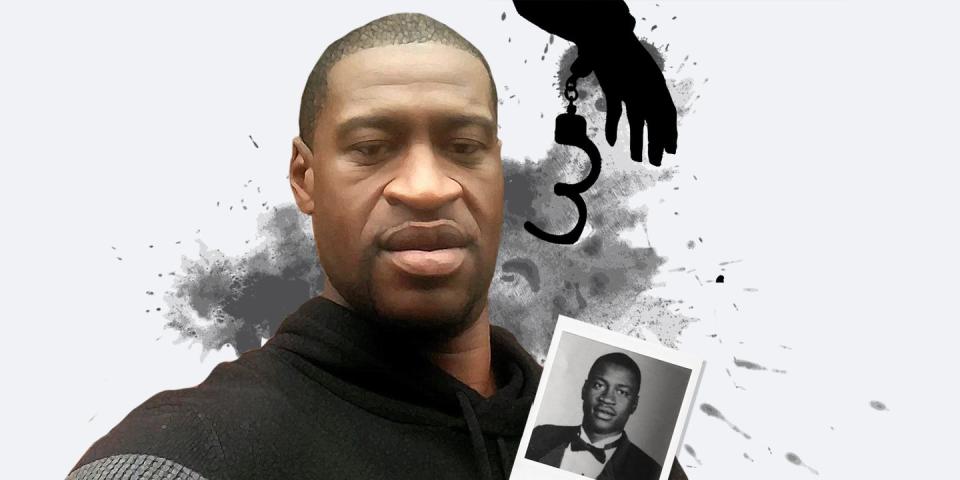

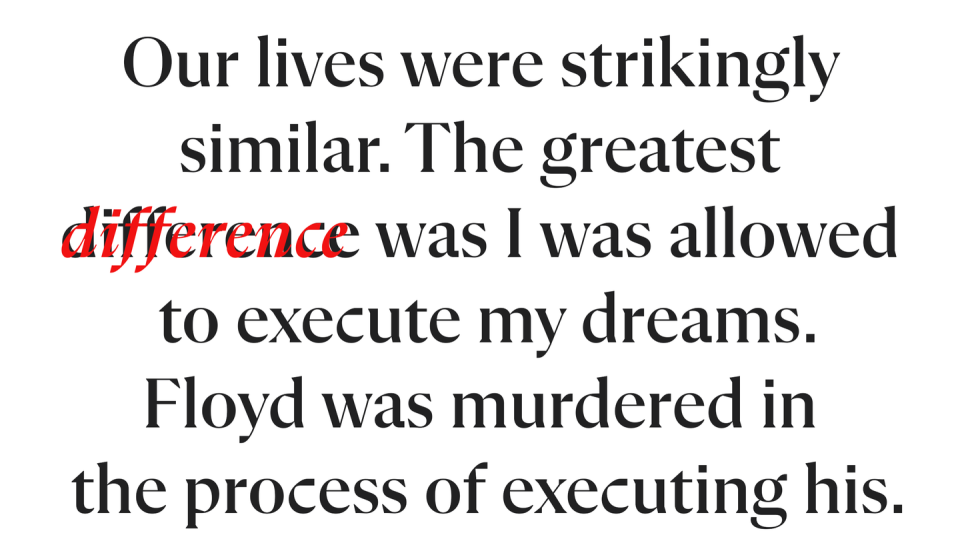

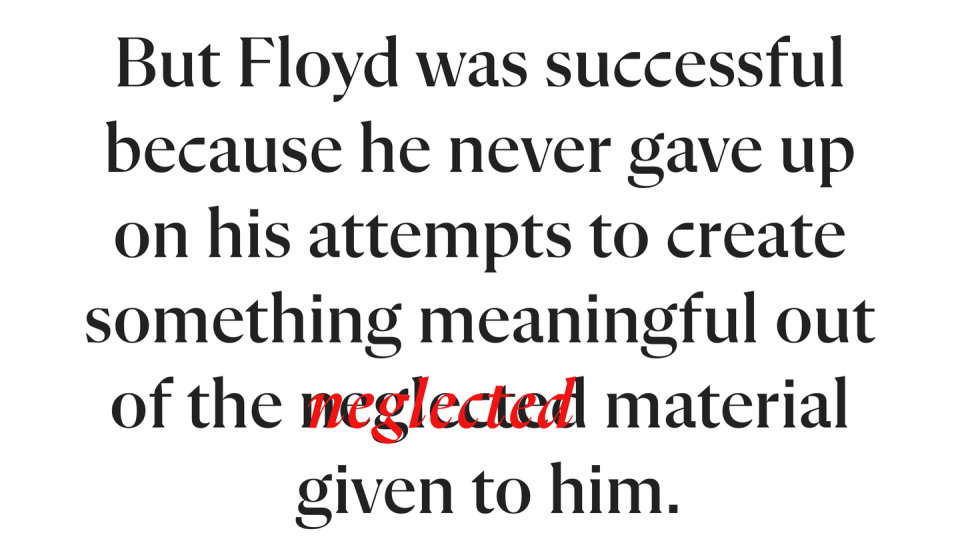

I, like Floyd, struggled with addiction, watched loved-ones struggle with addiction, sold drugs, and spent time in jail. Also, like Floyd, I never stopped reimagining the life I wanted. Until the day Floyd was murdered, Floyd was working to exectute his plans to become a truck driver. When I was arrested on Interstate 59, I had a plan to better my life. Overall, Floyd’s life is a humbling reminder of what success looks like. It’s punishingly easy to look at Floyd’s death and see a life full only of pain. But Floyd was successful because he never gave up on his attempts to create something meaningful out of the neglected material given to him. Like me, he looked down into his lap and saw a future for himself beyond his world’s limitations. Yes, I figured out a way to create a better life for myself, partly through self-education, but my success is also made possible because I never encountered Derek Chauvin while attempting to execute my dreams. I dreamed of journalism, Floyd dreamed of driving trucks. Our lives were strikingly similar. The greatest difference was I was allowed to execute my dreams. Floyd was murdered in the process of executing his.

You Might Also Like