Family of Charlotte man killed by police appeals after judge rules shooting justified

Listen to our daily briefing:

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Alexa | Google Assistant | More options

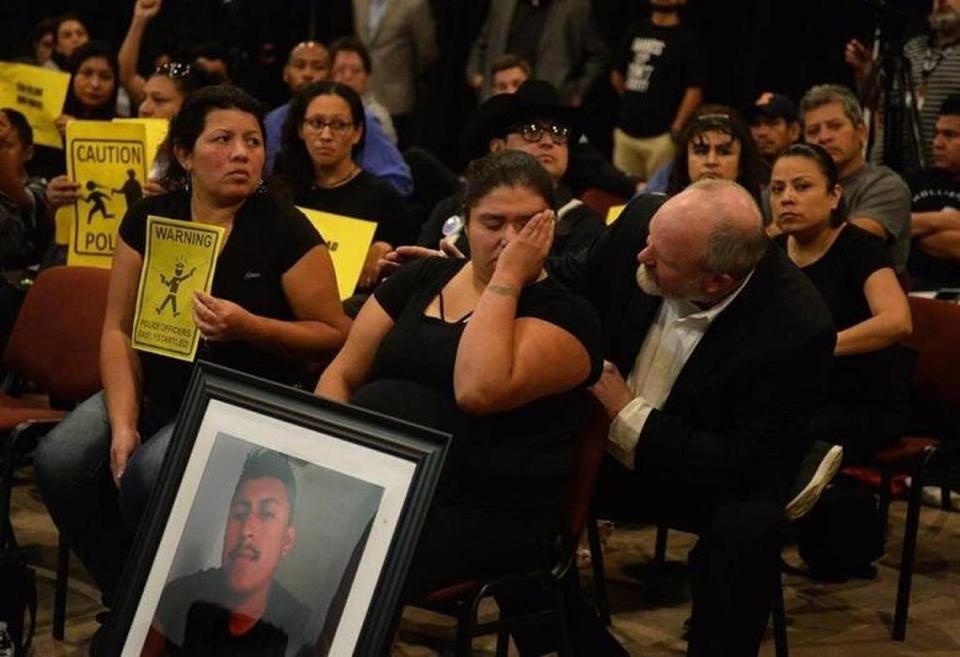

The family of a Charlotte father fatally shot in 2017 during a six-second confrontation with Charlotte-Mecklenburg police has appealed a federal judge’s decision to dismiss the wrongful-death lawsuit filed against the officer involved.

In an emphatic 20-page ruling, U.S. District Judge Robert Conrad of Charlotte said Officer David Guerra acted reasonably — and legally — on Sept. 6, 2017, when he twice shot Ruben Galindo. The brief but lethal confrontation occurred outside an apartment near Sugar Creek Road and Interstate 85 where Galindo and his family had been staying.

Under U.S. Supreme Court precedent and North Carolina law, police are legally justified to use deadly force if they have a “reasonably objective” fear of imminent death or serious injury for themselves or others.

In throwing out the lawsuit filed by Galindo’s partner, Azucena Zamorano Alemana, a month before it was to go to trial, Conrad ruled that Galindo’s actions met the legal standard necessary for Guerra to kill him.

“The reasonableness test is objective, and this horrendous set of facts justifies the use of deadly force in the face of an imminent threat,” Conrad wrote in his Sept. 30 ruling.

“Galindo’s series of poor decisions — drinking to excess while possessing and carrying a .380 semi-automatic handgun, executing a bad plan of surrender, and exhibiting a complete inability or unwillingness to heed safety suggestions or law enforcement commands — all combined to create ‘the tense, uncertain and rapidly evolving’ circumstances which required split second officer decision-making of a kind that case law ... instructs district courts not to second guess.”

The judge gave little weight to written and oral arguments by the family’s attorneys that challenged whether Galindo ever posed an imminent threat.

That included statements from two police officers at the scene who said that while Galindo had a gun at the time of the shooting, he held it upside down or pinched between his fingers and thumb and “not in a shooting grip.”

Another CMPD officer who was standing near Guerra outside the apartment later told investigators he was “surprised” that Guerra shot Galindo, according to filings in the case.

Conrad’s opinion also did not reflect one of the lawsuit’s major allegations, namely, that Guerra opened fire on Galindo seconds after giving him orders even though he and his fellow officers had taken protected positions near buildings and were not in imminent danger, as the law requires.

Charlotte attorney Luke Largess, who filed the lawsuit for Zamorano, on Tuesday filed an appeal of Conrad’s ruling to the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals in Richmond, Va. The court — the country’s second highest — handles cases from the Carolinas, Virginia, West Virginia and Maryland.

Largess told the Observer on Wednesday that he believes Conrad’s ruling will be reversed.

Guerra’s attorney, Lori Keeton, welcomed the judge’s decision.

Her client, she said in a statement that first appeared in the Charlotte Ledger, “has devoted his life to serving others — first through his military service and now through his career as a police officer with CMPD. In this lawsuit, the Court properly concluded that Officer Guerra did not violate Mr. Galindo’s rights.”

Guerra, a former Marine who served in the Iraqi War, was hired by the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department in 2013, remains on the force.

CMPD used ‘paramilitary’ tactics in shooting man with hands up, lawsuit claims

‘Imminent threat’?

Zamorano’s lawsuit named Guerra and the City of Charlotte as defendants. Courtney Suggs, a second police officer who fired at Galindo but did not hit him, was dropped from the lawsuit last year.

The complaint alleged that Guerra and his colleagues used “paramilitary tactics” to unnecessarily escalate tensions; that Guerra opened fire in a matter of seconds without ever being at risk; that police failed to recognize that Galindo was experiencing a mental health crisis, and that Galindo died with his arms raised in surrender.

The lawsuit also accused the city of failing to properly train its police officers.

On the night of his death, Galindo, Zamorano, their 3-month-old daughter Ruby and Zamorano’s other children, were all together in the friend’s apartment in northeast Charlotte.

Galindo, a 29-year-old native of Mexico, had been drinking heavily when he twice called 911, telling the dispatchers in a rambling and occasionally delusional fashion that he wanted police to take him into custody for an upcoming court date. He also wanted to give them his gun.

Toxicology reports later would later determine that Galindo’s blood-alcohol level was almost three times the legal limit. He had also been experiencing recurring delusions that he was being followed.

According to case records, Galindo told the dispatcher twice that his gun was not loaded. “No tengo balas.” Translation: “I have no bullets.”

But Galindo also was warned by the dispatcher at least six times to leave his weapon inside the apartment before surrendering to police. Instead, he had the firearm in his pocket when he appeared at the door to the patio.

As police shouted “manos” — which is Spanish for “hands” — Galindo raised his arms before eventually pulling out the gun. Officers at the scene repeatedly shouted at him in English to drop it. Then they opened fire.

A weapon was recovered at the scene. As Galindo had promised, it was not loaded.

The lawsuit claims Galindo was killed trying to comply with the only Spanish command he heard — to raise his hands. Given Galindo’s limited English, officers should have delayed confronting Galindo until an interpreter was on the scene.

Police could have waited, according to the lawsuit, because Galindo “did not pose an imminent threat to anyone.”

Police chief, experts clash over whether deadly Charlotte shooting was justified

Conrad, a former U.S. Attorney, ruled otherwise.

“The split-second decision-making confronting Guerra and thus any reasonable officer in his position, takes into account all that can be seen and heard on the video footage, and all that led up to that moment. It leads this Court to the conclusion that a reasonable officer in Guerra’s position would have been justified in perceiving an imminent threat,” Conrad wrote.

“A reasonable officer in Guerra’s position did not have to wait (until a gun was pointed at him); did not have to trust a man believed to be delusional, and possibly homicidal or suicidal; a man who had refused every law enforcement directive aimed at keeping him and others safe.”

Debate over use of force

Conrad’s ruling likely will renew debate locally over the broad legal protections surrounding police use of force. Supporters say the law appropriately reflects the volatile nature of police work in which split-second decisions can determine life or death.

Critics say the law too often upholds needless police violence. An expert witness in the trial of Derek Chauvin, for example, testified that the former Minneapolis police officer was justified in kneeling on George Floyd’s neck for more than nine minutes because Floyd posed an imminent threat. Floyd died. Chauvin was convicted of murder in April.

In 2017, the Mecklenburg District Attorney’s Office declined to bring criminal charges against Guerra and Suggs, arguing — as Conrad would do — that it was reasonable for Guerra to shoot Galindo.

“While it is entirely possible that Galindo’s intent was to surrender to police and give them the firearm, other alternatives that could have been lethal to the officers, neighbors in the community or other occupants of the residence were just as likely based on the information available to Officer Guerra in the seconds he had to evaluate the situation,” then-District Attorney Andrew Murray wrote.

“This officer-involved shooting was indisputably tragic, but it was not unlawful.”

Two experts in police use of force who were shown the shooting video at the time of Murray’s decision said the killing was unnecessary. One said police had not given Galindo adequate time to respond to their commands before they shot him.

Another, political scientist and former law enforcement officer Phil Stinson, said the case points out the broad protections of police within the law.

“It’s unfortunate that a police shooting can be found to be legally justified yet unnecessary and inappropriate,” Stinson said.

“In my view, this case should have gone to a grand jury.”

Que Pasa Charlotte, a Spanish-language publication in Charlotte, reacted to Conrad’s ruling this way:

“There was no justice in the death of Mexican father Ruben Galindo ...”