Fall River was an Underground Railroad junction. These 6 homes are part of Black history

Fall River’s history, like all of American history, is inextricably linked to the slave trade, the kidnapping and involuntary servitude of millions of African people. The city’s first textile mills built in the early half of the 19th century — the foundation upon which the city’s fortunes stood — were fueled by cotton from fields in the American South, picked by generations of Black people forced into slavery from birth to death.

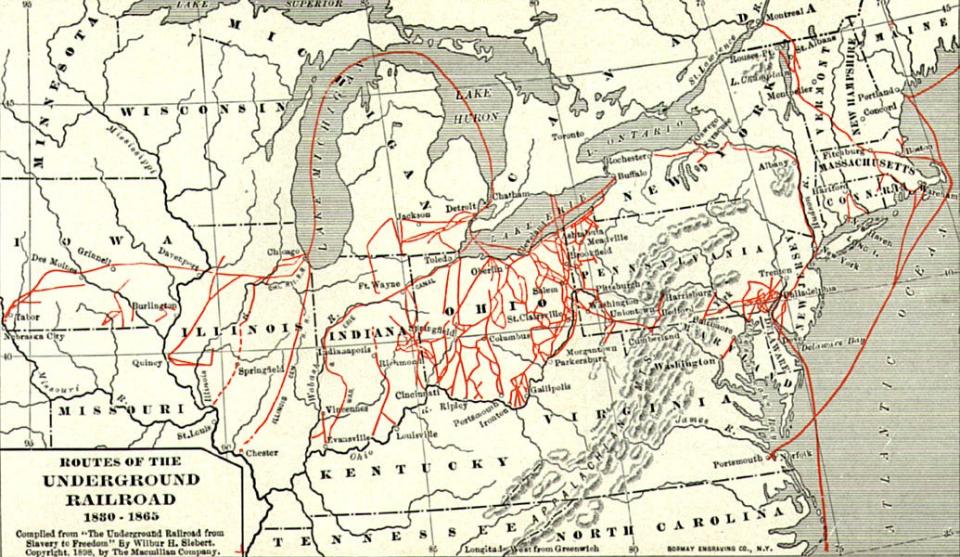

But Fall River was also a notable hub of anti-slavery activity in the decades before the Civil War. For several decades in the early 19th century until 1865, Fall River was an important stop on the Underground Railroad, the network of safe-houses and collaborators who helped Black people escape the South and slave-catchers. Runaways bold and lucky enough to make it from the cruel horrors of the plantations to Norfolk, Virginia, would be stowed away on commercial ships to Wareham or New Bedford, then to Fall River, and on to Rhode Island and points north.

'Anti-Slavery Days': Fall River's role in the Underground Railroad is the focus of new book

“Conductors” on the Underground Railroad would take in desperate fugitives, starving and sometimes clad in tattered rags or even costumes, hide them from the law until their next stop was arranged, and then send them on to Rhode Island, Vermont, and finally Canada, which had abolished slavery decades earlier and gave Black people equal rights under the law.

The conductors and their "cargo" were criminals, breaking the Fugitive Slave Law. The white conductors risked steep fines and imprisonment. The Black fugitives risked being sent back to the hell of slavery and likely punishment that could have meant whipping, branding or mutilation. Because of the secrecy, it will never be known for sure how many Black people passed through Fall River, or even how many stations there were.

But several people in Fall River were known to be conductors on the Underground Railroad, and their homes known to be “stations.” Most are still standing. In honor of Black History Month, here’s a look at some of the places in Fall River known to have harbored Black people on their journey to freedom.

Fall River strong: From Rhodes scholars to MMA fighters, 10 notable city natives

40 Second St. — N.B. Borden house

Nathaniel Briggs Borden was a prominent Fall River businessman and politician who served in the state Legislature and became Fall River’s third mayor. His third marriage, in 1843, was to Sarah Gould Buffum, from an outspoken, radical abolitionist family that also produced “the conscience of Rhode Island,” Elizabeth Buffum Chace. The couple opened their home to runaway slaves for years and kept them safe from “man-stealers.” The home was demolished many years ago — it stood about where the Webster Bank on Sullivan Drive stands now.

175 Rock St. — Abraham Bowen House

Abraham Bowen Jr. was a wealthy son of Fall River royalty — his father was a cotton mill agent who successfully got Fall River change its name to Troy, a move that lasted from 1804 to 1833. Bowen was in the printing business and had his own newspaper, called the Fall River All Sorts, what we might now think of as an alternative publication, published from 1843 to the 1850s. He was a man of “strong individuality” and “marked eccentricity,” according to a biography — and he also opened his Rock Street home to fugitive slaves heading north. The house is still here, though it’s since been converted to apartments.

'It was horrific': Irving Street apartment house fire wasn't the first fire on that block

263 Pine St. — Isaac Fiske House

Dr. Isaac Fiske was a Quaker who studied medicine and taught penmanship for years. He owned a private boarding school in Scituate, Rhode Island, for 10 years, then settled in Fall River to practice medicine as a homeopath. He was also a staunch abolitionist involved in anti-slavery meetings, and used his Pine Street home as a way station for slaves — including, it’s rumored, Henry “Box” Brown, a runaway who had himself mailed in a wooden crate from Virginia to Philadelphia. Today, the Preservation Society of Fall River owns the Fiske house. It's a multi-tenant residence today. The Preservation Society has acquired items from a distant relative of Fiske, and plans to open the basement as a museum dedicated to the Underground Railroad within the next few years.

335-337 Pine St./190 Rock St. — Slade Double House

Albion King Slade and his wife, Mary Bridge Canedy Slade, lived at this house on the corner of Pine and Rock streets with three addresses. Both were teachers, with A.K. Slade becoming principal of Fall River High School, and his wife a writer and editor who also penned a number of gospel songs. They harbored runaway slaves at their spacious home, helping them avoid slave-catchers and the local sheriff. The building is today home to a law office.

Buying or selling a home?: Fall River real estate market staying hot

2634 N. Main St. — Squire Canedy House

Mary Bridge Canedy Slade, mentioned above, was one of 13 children of Susan Hughes Luther Canedy and William Barnabas Canedy, the postmaster of Fall River’s Steep Brook neighborhood. The Canedy family was deeply involved in the anti-slavery movement — all seven daughters became teachers, and two went South to teach the children of newly freed Black families. A grandson, named after his grandfather, fought for the Union in the Civil War and died in 1862 at age 22. Their home, used as an Underground Railroad station for fugitives heading to Rhode Island, is today a two-family home.

28 Columbia St./451 Rock St. — Fall River Historical Society

The building that now houses the Fall River Historical Society used to be located a mile and a half southwest, at Fountain and Columbia streets, which at the time was on the border between Massachusetts and Rhode Island. The land was a wedding gift from Andrew Robeson to his son, Andrew Robeson Jr. and his new wife, Mary Arnold Allen, who built a granite mansion on the site in 1843. They soon converted their wine cellar to a hiding place for fugitive slaves, accessible via secret door hidden in the library. The legacy was kept up by a Quaker abolitionist, William Hill Sr., who bought the home 11 years later. The house was moved to its current location in 1869 by another owner — and by then, the state border had been moved 2 miles south. The secret door to the wine cellar is still intact. It's visible when open to the public, but the Historical Society is currently undergoing renovations to its heating and ventilation system.

Dan Medeiros can be reached at [email protected]. Support local journalism by purchasing a digital or print subscription to The Herald News today.

This article originally appeared on The Herald News: Fall River has role in Black history as Underground Railroad station