Don't call Senate candidate Marsha Blackburn a feminist, even if she is one

GRANVILLE, Tenn. — When U.S. Rep. Marsha Blackburn first considered running for Congress almost 30 years ago, she went to see a prominent player in Tennessee politics, a man she knew and respected, to solicit his advice and talk about her prospects.

At the time, Blackburn was a suburban mother of two young children, a fashion consultant who had appeared dozens of times in the pages of the Tennessean, the local daily newspaper — first as a model and then as a source on fashion trends. (“Every man needs a chambray shirt in his wardrobe,” she advised readers in 1992.) Blackburn was — as she is now — a fixture on the local society pages, written up for her involvement in charity dinners and volunteer work.

But Blackburn was also a rising star in local Republican politics. In 1977, when she was pregnant with her first child, the Mississippi native had helped found a local club for young Republicans in her adopted hometown of Williamson County, Tenn., near Nashville, when the region was prominently Democratic. In 1989, she was tapped as chair of the Williamson County GOP, the first woman to hold the job and one of the few female party chairs in the state at the time. She was a successful fundraiser and widely credited for helping grow the party in what is now one of the most conservative counties in Tennessee.

Still, as Blackburn began to consider her own political future, she was met with disdain. The political player, whom she won’t name, had been friendly before. But when she broached the subject of her running for office, he turned cold. “He never came from behind his desk,” Blackburn recalled. Up to that time, Tennessee voters had never elected a woman to Congress, except four women who had won special elections or been appointed to succeed their husbands after their deaths.

“You’re wasting your time, you’re wasting my time, you’re wasting money,” he told her. ‘I don’t see how you would ever win.”

She left deflated but determined to prove him wrong, as she eventually did, winning a state senate seat in 1998 and, four years later, the congressional seat she had eyed for more than a decade. The man who had dismissed her ambitions at first came around later as a supporter and campaign donor. The lesson she took from the experience is that “you never let these obstacles and these challenges define you. There is nothing that says you as a female, or you as a conservative female, are unworthy. Not anything.”

In her eight terms in Congress, running now for the U.S. Senate seat being vacated by two-term Republican Bob Corker, she has grown and changed with the times. The question she faces is, has Tennessee changed enough?

If she wins, Blackburn would not only be the first woman to represent Tennessee in the Senate, she could potentially be the first woman elected to a statewide office. (State House Speaker Beth Harwell and U.S. Rep. Diane Black, the only other woman in the state’s congressional delegation, are seeking the GOP nomination for governor but face a crowded primary this August.)

Yet it’s a milestone that Blackburn almost never mentions — not in her campaign ads and not to voters as she canvasses the state in a race many believe will decide which party gains majority control of the Senate next year. Democrats need just two additional seats to regain majority, and Phil Bredesen, the former Democratic governor of Tennessee and Blackburn’s opponent, is considered one of the party’s best prospects.

In early polls, Bredesen, a political centrist who is popular with many Republicans, narrowly leads Blackburn, who holds one of the most conservative voting records in the House. A Mason-Dixon poll released in April found Bredesen with a three-point advantage over Blackburn, 46 percent to 43 percent, among registered voters — a stunningly close race in a state that has gone bright red for Republicans in the last several elections and where voters overwhelmingly backed Trump in 2016.

Blackburn, a passionate ally of Trump who backed him early in his 2016 bid, has built her campaign around her unwavering loyalty to the president, trashing Senate Republicans who “have acted like Democrats or worse” and vowing that she will work to enact his agenda, including on immigration and his push to repeal the Affordable Care Act.

But many believe the race won’t be decided purely on Blackburn’s efforts to hold the line among Republicans. She will also likely need the help of female voters, who were pivotal in Trump’s victory in Tennessee two years ago but are not as enamored of the president today. While 59 percent of Tennessee men approve of Trump, according to a Vanderbilt University poll released last month, just 48 percent of women do — down more than five points since the election.

Part of Bredesen’s early strength is his appeal among women. The Vanderbilt poll found 72 percent of women viewed Bredesen favorably, compared to 46 percent for Blackburn. When presented with the question of how they would vote if the election were held today, the Mason-Dixon poll found the ex-governor with an 11-point lead over Blackburn among registered female voters.

Even running in what has been billed as the “year of the woman” because of the record number of female candidates and increased activism among women voters, Blackburn has done almost nothing to call attention to her own potentially history-making bid or her personal story as a woman who has broken gender barriers in business and in politics. She explains the omission by saying she wants voters to back her because she is “the most qualified,” not because she is female.

In some ways, it’s a surprising stance for Blackburn, a political spitfire and constant presence on cable news who has given motivational speeches and even wrote a book encouraging women to see themselves as “warriors” in a society that more often elevates men as “great leaders.” Blackburn is careful to say she is not of the “men-are-pigs school of feminism.” She argues that women should “rise up and take places of leadership alongside men.” But while being a passionate advocate for women to embrace leadership roles, she has sometimes offered a mixed message on how she applies these rules to her own career.

In a state that has been slow to recognize women in politics, Blackburn has been careful to avoid the subject of gender in her own campaigns, including her current race, where she has sounded themes more commonly heard from male candidates, bragging about shooting skeet and mentioning that she carries a handgun in her purse. When she arrived in Washington in 2003, she pointedly asked to be called “congressman” instead of “congresswoman.” “It’s the name of the job,” she explained.

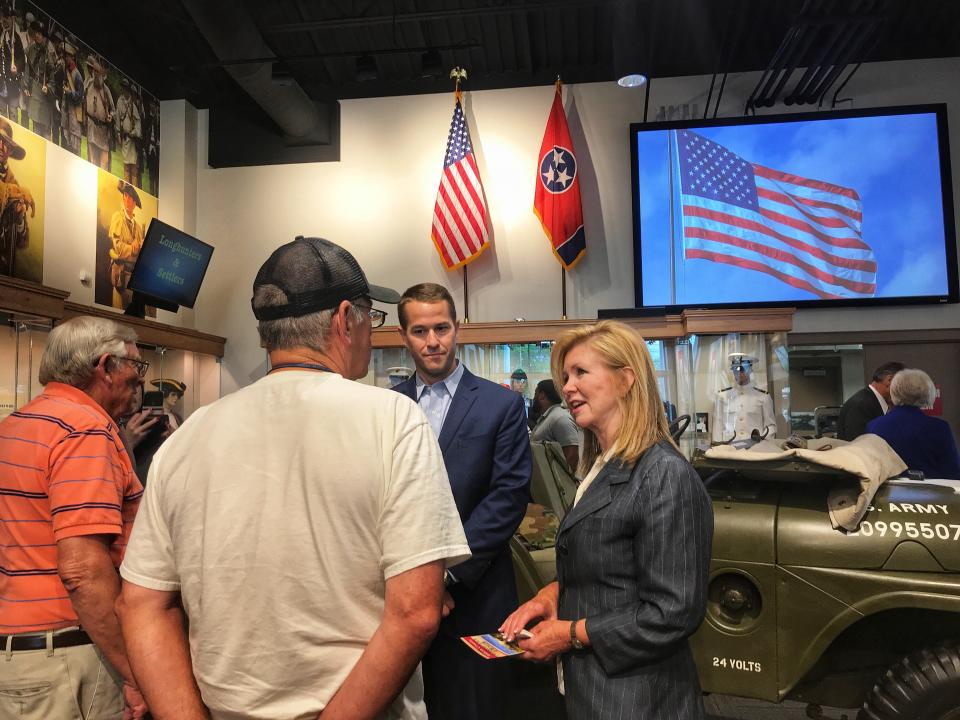

On a recent Saturday, Blackburn introduced herself simply as “Marsha,” as she campaigned during a blisteringly hot afternoon at an outdoor festival here. She handed out business cards, dispensed hugs and posed for pictures, including with a man who called the petite lawmaker “little woman.” She presented herself as a foot soldier for Trump who will help continue his agenda, but spoke less about herself.

“I go at it as [if] I am earning every vote,” she said, briefly taking shade under a large oak tree. “I have always felt that you work hard and you give your best effort, and you are hopefully rewarded, no matter who you are.”

Born in Laurel, Miss., the second of three children born to a father who sold oil-drilling supplies and a stay-at-home mom, Blackburn — then known by her maiden name, Marsha Wedgeworth — first made headlines in the local newspapers when she was just 13. It was 1966, and she had won a statewide chicken-cooking contest in Mississippi that had earned her a bid to the national championships in Maryland that summer.

An enthusiastic member of the local 4-H club, she had been competing since age 10, winning contests in gardening and sewing. But Blackburn’s cooking was the talk of the region. Her winning dish that year was a chicken casserole that involved a medley of canned soups, including cream of mushroom and chicken noodle, and the exotic detail (for the South, anyway) of adding chow mein noodles. She had been cooking the dish over and over, determined to master the recipe. “Most of the family is already getting tired of chicken, but I’ve got to keep practicing,” she told the Clarion-Ledger in nearby Jackson, Miss., in April 1966. The story ran with a photo of the future lawmaker, with a short bob haircut and a gingham apron, grinning and holding a piece of chicken. Her casserole placed seventh in the nation.

Blackburn would eventually win a 4-H scholarship to Mississippi State University after winning a national contest for excellence in food preservation. (A 1968 write-up of the scholarship noted she had canned more than 1,250 quarts of food and nearly 5,000 pounds of meat — saving her family an estimated $15,000 in food costs.) She majored in home economics.

But Blackburn had bigger dreams than simply being the world’s greatest homemaker. While she was very much her mother’s daughter — a girly girl who had an interest in fashion and would win the beauty pageant at the Laurel Oil Festival — she also loved going to work with her father, who often got late-night calls from customers in need of emergency parts. A night owl who even today operates on little sleep, she would hit the road with her dad to keep him company. “I would pop into the front seat of that pickup truck, and we’d have a thermos of coffee and Tammy Wynette on the radio, and off we would go to wherever they were putting in an oil rig,” Blackburn recalled.

She began to dream of becoming a salesman like her a dad, a goal her parents encouraged. Blackburn said she was raised in a conservative, churchgoing household where her family never spoke of limitations on what women could do professionally, even though the women’s liberation movement hadn’t yet taken hold in the South.

“It was shocking to me when I went to college, and I found out there were people who expected that you would treat men differently or more favorably and women less so,” she said. “I was just never accepting of that as a premise. I said, ‘Well, if it’s a barrier to break, you go break it.’”

And Blackburn did. Her brother James, who is two years older, had spent his summers during college selling Bibles and other books door-to-door for Southwestern Company (now known as Southwestern Advantage), a Nashville-based publishing outfit that employed many prominent conservatives in their youth, including Rick Perry and Jeff Sessions.

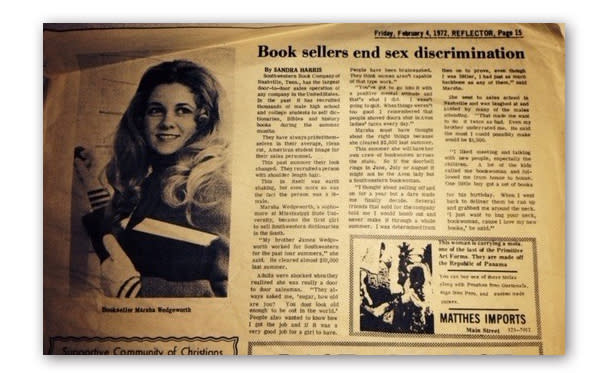

Blackburn saw how much money her brother was making (upwards of $10,000 one summer) and quickly applied. The company, which had no women on its sales team, initially rejected her. Their student reps usually traveled to Nashville for sales school before being deployed to other cities to go door-to-door working as long as 80 hours a week, on commission. The company didn’t think that was the right environment for a young woman like Blackburn, who was not yet 19.

Some of Blackburn’s male friends made of fun of her, suggesting she lacked the stamina to spend an entire summer selling books door-to-door. But their skepticism only made her want the position “twice as bad,” she said. It was sexist, she argued, to think a woman couldn’t do the job. Soon, the company relented. They would hire her as their first female saleswoman, but on one condition: She could get her sales training in Nashville, but then she would have to go back home and live with her parents and work from there. She couldn’t travel like the guys.

That summer, back home in Laurel, Blackburn took her catalog of books and trudged from porch to porch in the oppressive heat of the summer. Her hair was big and curly, and she looked younger than the college sophomore she was. Many prospective customers, mostly men, found her to be a curiosity. “Sugar, how old are you? You don’t look old enough to be out in this world,” one man told her.

It was good training, she said, for her future career in politics. She learned how to talk to people and engage them, to keep doors from getting slammed in her face. Some of her toughest customers were women, who didn’t like having their afternoon soaps interrupted by a knock at the door. But Blackburn would entice them by showing off a giant cookbook — “The Encyclopedia of American Cooking” — and she would get invited in to pitch her wares during the commercial breaks.

“That cookbook opened a lot of doors for me,” she recalled.

That summer, Blackburn distinguished herself as one of the company’s top salespeople — earning enough to pay off her tuition for her sophomore year and to buy a bright blue Ford sedan, which she nicknamed the “Can-Do.” She was so prolific that, the following summer, the company decided to hire more women and expand its offerings to female customers, introducing more cookbooks and titles geared toward women and children. Blackburn recruited her Chi Omega sorority sisters and other women she knew into the company, and while they were still required to live at home, they would hold their sales meetings at a Shoney’s restaurant in Jackson every Sunday.

Her college newspaper documented her efforts in a glowing profile, calling her a lady trailblazer who had ended “sex discrimination” at the book company. “People have been brainwashed that they think women aren’t capable of this type of work,” Blackburn told the paper. By her third year working for Southwestern, when she had been promoted to sales manager, there were scores of women working for the company. And they relaxed the rules, allowing Blackburn and the women on her sales team to work in Atlanta for the summer.

The gig soon became more than just a job to Blackburn. While the women’s movement was largely associated with liberal politics, Blackburn, a conservative, began organizing meetings at school with her female classmates, encouraging them to register to vote and become more politically active. And she became obsessed with trying to bust the conventions of the South that women were destined to be only wives and mothers. Along with her sorority sisters, she began pushing local businesses to hire more women, particularly for male-dominated jobs like sales. Part of it was motivated by self-interest: Blackburn was nearing graduation and she was worried about finding a job in Mississippi, where employment opportunities were limited for everyone, not just women.

But for all of her efforts to break the glass ceiling at Southwestern, Blackburn was eventually forced out. In the fall of 1974, a year after she graduated college, she married Chuck Blackburn, a young man from Texas who was also a sales manager at Southwestern. (Though they worked at the same company, he first saw her on television, where she was appearing on a game show, and, afterwards, looked her up.) “I found out they had a nepotism rule, and I had to give up my job,” she said.

The couple ultimately moved to Brentwood, Tenn., outside Nashville, where Blackburn got a job in fashion merchandising and promotion. She occasionally modeled — appearing in fashion layouts in the Tennessean — and in her spare time, she began dabbling in local politics, putting her on a path where she would break more barriers.

Blackburn didn’t win the first time she ran for Congress in 1992, when she took on a well-known and well-financed Democratic incumbent. But in 1998, she won a seat in the state Senate — a significant accomplishment given that just 18 women were serving in the entire Tennessee legislature at the time, one of the lowest rates of female representation in the country.

According to those who know her, Blackburn hasn’t changed much since her early days in politics. Back then, as now, she positioned herself as a far-right conservative — a notable tack in Tennessee, a state that until recent times had a long history of electing moderate politicians from both parties. She campaigned on curbing big government and came out against abortion and same-sex marriage. “Good luck to anyone trying to find any sign she’s changed dramatically on any position,” said a GOP strategist in Nashville, who declined to be named. “She has been a very, very consistent conservative, even if it means taking on her friends.”

Her defining moment as a state legislator came in the summer of 2001, when she tangled with a close ally, Gov. Don Sundquist, a Republican, who had proposed a state income tax to solve a budget crisis.

Blackburn emerged as one of the strongest critics of the proposed tax. After hearing word of a possible deal between the governor and other Republicans in the Senate on the measure, she had aides alert local conservative radio hosts who told their listeners about the last-minute vote. Many of them stormed the state capital in a wild protest in which one opponent of the tax punched through a glass window in Sundquist’s office. Though some lawmakers criticized Blackburn for her role in whipping up the protest, which she later said had gone too far, she was ultimately credited for going up against members of her own party to stop the income tax — an effort she regularly reminds voters about today.

The battle against the income tax gave her the boost she needed to make another bid for Congress, and in 2002, she ran again and won — becoming the first woman elected to a full term in the U.S. House in Tennessee without the benefit of a husband’s coattails. But in that campaign and the others in the 16 years since, she played down her status as a woman — though other women active in Tennessee politics say this is not unusual.

“We don’t talk about it. We just do it,” said Susan Richardson Williams, a political strategist from Knoxville who in 1982 became the first female chairman of the Tennessee Republican Party. “Maybe that’s unusual, but that’s who we are, and that’s how it is in Tennessee. We don’t brag. We go out, we run, we get elected. … It wasn’t anything everybody got up and touted any time we made history. It was just the way it was, the way it has been.”

In Congress, Blackburn has occasionally spoken out about the need for her party to be more inclusive for women. A member of the House leadership — she is a deputy whip — Blackburn has argued there should be more females in party leadership roles and argued the party has not done enough to appeal to women voters. And she wrote a book, “Life Equity,” that cited her own experience in politics to encourage women from all walks of life to rise up, take on leadership roles and see themselves as equals to men.

But Blackburn has also been criticized for taking positions that some describe as anti-woman. Among other things, she has repeatedly argued against legislation mandating equal pay for women. And in 2009, she voted against the Lily Ledbetter Fair Pay Act, which would have made it easier for women to pursue employment discrimination cases based on pay differentials with men.

Asked why she has opposed bills aimed at promoting gender quality in the workplace, Blackburn has argued that women want recognition over equal pay. “You know, I’ve always said that I didn’t want to be given a job because I was a female, I wanted it because I was the most well-qualified person for the job. And making certain that companies are going to move forward in that vein, that is what women want,” Blackburn told “Meet the Press” in 2013. “They don’t want the decisions made in Washington. They want to be able to have the power and the control and the ability to make those decisions for themselves.”

Looking toward November, Blackburn’s quest to become the first woman from Tennessee to win a U.S. Senate seat could ultimately come down to her relationship with Donald Trump.

While many Republicans have distanced themselves from the president in recent months — not unlike past midterm elections where members of the sitting president’s political party have run away from the White House — Blackburn has embraced Trump with an enthusiasm remarkable even in the current GOP. In the video announcing her bid for Senate, she fully endorsed some of the president’s most controversial proposals, including the construction of a wall along the U.S. border with Mexico, which local polls show is not as popular in Tennessee as in some other Republican states.

When Blackburn introduces herself to voters, she often talks more about Trump than her own policies — touting his record on conservative judges, tax cuts and the record-low unemployment rate, promising she’ll help him continue his work. In parts of Tennessee outside her district, which runs from the suburbs south of Nashville a couple of hundred miles west toward the suburbs of Memphis, this is a smart introduction, as she is not as well-known, in spite of her frequent television appearances.

On a recent Saturday, she spent a little over an hour mingling with voters at a pancake breakfast in Fairfield Glade, a leafy retirement community in the center of the state. As she moved from table to table, clutching a paper plate of pancakes in the shape of Mickey Mouse that had been made especially for her, several voters asked her to reaffirm her support of Trump. It was a question that came up again and again.

“Will you stand with my president?” one woman asked her.

“That’s why I am running,” Blackburn replied.

While Trump remains popular in Tennessee, there are certain risks to holding him so closely. Polls show many female voters here, including Republicans, strongly disapprove of his rhetoric towards women. And speaking one on one, many Republican women say they have not gotten over the infamous“Access Hollywood” tape of Trump making demeaning remarks about women — although they still voted for him because they didn’t want to support Hillary Clinton.

While many of Blackburn’s colleagues, both men and women, abandoned Trump in the aftermath of the video, she did not, displaying a loyalty that Trump has not forgotten. In recent months, he has appealed to his nearly 53 million Twitter followers to support Blackburn, a boost that helped her avoid a potentially messy GOP primary. And he showed up in Nashville to campaign for her, trashing Bredesen and inviting Blackburn to share the stage.

But Blackburn has had rare moments of disagreement with the president. Last summer, after Trump went on a Twitter tear attacking MSNBC host Mika Brzezinski’s appearance, Blackburn posted a note on her Facebook page criticizing Trump’s comments as “inappropriate and pointless” and a sign of the nation’s crumbling civil discourse.

“In this era of 24/7 worldwide news, the president of the United States represents each and every one of us on the world stage,” Blackburn wrote. “We are right to expect a higher level of civility, graciousness and diplomacy from our president. We expect the individual who holds the office and the title to rise above the hubris and noise of the day.”

But Blackburn has not been nearly as critical of the president since. In Fairfield Glade, Marcia Storrison, a registered Democrat from Michigan who recently retired to Tennessee, approached Blackburn and pressed her on her alliance with Trump.

“How as a woman can you support Donald Trump?” Storrison asked. “He treats us like we’re second-class,” she said, and has taken women’s rights “back to the 1950s.”

Blackburn stood quietly for a moment and then began to carefully tick through talking points about Trump’s handling of jobs and the economy. “He’s working very hard for us,” she said, carefully.

“The economy was good under Obama,” Storrison shot back.

“Well, we’re going to have to disagree on that,” Blackburn replied.

Asked later what she wanted Blackburn to say, Storrison admitted she didn’t know. “I was trying to get her to tell me, woman to woman, how she can support him,” she said. “Because I just don’t get it.”

Long before Bob Corker announced that he wouldn’t seek reelection, Trump administration officials, including the president’s former adviser Steve Bannon, had been privately pushing Blackburn to run in hopes of adding a reliable Trump ally to the Senate.

But when Bredesen, the last Democrat to win a statewide race in Tennessee, emerged from political retirement last December to jump into the race, some Republicans, both in and out of Tennessee, panicked. They pressed Corker to reconsider his decision to retire, raising concerns that Blackburn might be too conservative to win independents or could alienate mainstream Republicans.

Andrea Bozek, a spokeswoman for the Blackburn’s campaign, castigated the skeptics in an interview with the Washington Post. “Anyone who thinks Marsha Blackburn can’t win a general election is just a plain sexist pig,” she declared.

Corker later confirmed that he had considered reentering the race, but said he was sticking with retirement. Finally, in April, he threw his support behind Blackburn in an endorsement that was tepid at best. Though he wrote a check to Blackburn’s campaign and told reporters he would “support the Republican nominee” in the race, Corker told reporters he would not campaign against Bredesen, a longtime friend whose moderate politics he shares.

In some ways, Corker’s public comments weren’t surprising. Some Republicans had privately wondered if he would endorse Blackburn at all. But even some party officials who aren’t close to Blackburn have been critical of Corker’s behavior towards her, calling her a victim of the “boys club mentality” that still permeates the state’s politics.

But Blackburn won’t go there. While she reiterates again that she doesn’t want to campaign as the woman in the race, the Tennessee lawmaker, standing under that oak tree on a hot Saturday afternoon, allows herself a rare moment to consider the history she could make.

“I think that women who have worked hard do want to be recognized as achieving that success, as they should. … Is it change? Yes. Is it nontraditional? Absolutely, especially in a place like Tennessee,” she said. “You’ve never had a female win a statewide office, run for the U.S. Senate. I’ve spent much of my life breaking those barriers. This would be a nice one to break.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

Obama official: ‘We should have done more’ on Russian interference in 2016 election

Sage grousing: Senators charge Interior is holding up conservation grants

California’s Gavin Newsom wants to lead the way to a post-Bernie, post-Hillary party

The Eighth Circuit strategy: How abortion foes are lining up cases to challenge Roe

Photos: Historic summit between Trump and North Korea’s Kim in Singapore