Cascades bicentennial journey: Waterfall to baseball field to brownfield to pinnacle park

About 200 years ago, before there was an amphitheater, sidewalks or splash pad, there stood a waterfall – the original "Cascades."

Two commissioners sent by Gov. William Duval reported that the Cascades waterfall would be a source of mill power for the pioneer settlers of Tallahassee, according to an article in the Tallahassee Democrat from 1974, the year the city celebrated its 150th birthday.

John Lee Williams of Pensacola and W. H. Simmons of St. Augustine were tasked with surveying the land. In a letter to Richard Keith Call dated Nov. 1, 1823, Williams described the Cascades area that would contribute to the city being named the capital city.

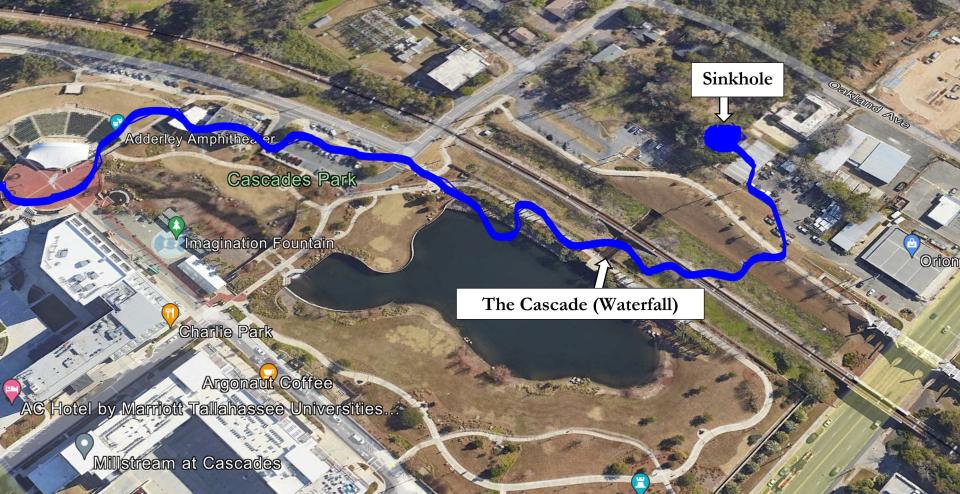

"Directly east of the old fields runs a stream of water which you must recollect. This stream, after running about a mile south pitches about twenty or thirty feet into an immense chasm, in which it runs 60 or 70 rods (990 to 1,125 ft.) to the base of a high hill which it enters among…..rocks full of shells and other fossils," the 1974 article quotes.

That stream emptied into what is now the lower parking lot of Leon High School off of Tennessee Street.

But there's no evidence that the hydropower of the waterfall was ever used. Instead, the railroad was built, and workers plugged the sinkhole where the water flowed underground.

"According to accounts from eye-witnesses, this ruined the spot's natural beauty," the 1974 article reads.

It turned the whole area into a marshy swamp, and later, the city used it as a trash dump in the 1920s.

Then came Centennial Field.

Baseball, the Babe and Bloxham Street

Boca Chuba Pond, a stormwater pond at Cascades Park designed to flood during major storm events, was once a proving ground for athletic prowess.

![A Sept. 26, 1970 rally for the Reubin Askew campaign for governor held at Centennial Field in Tallahassee. Askew is in a blue shirt on the dais leaning over to touch the shoulder of his running mate for Lt. Governor, [1961-1971 Secretary of State] Tom Adams. Centennial Field, built in 1924 for Tallahassee's 100th anniversary and demolished in 1975, served as the capital city's chief sports and civic arena for decades. The site, off South Monroe Street, is now Cascade Park.](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/8qz0tTcB0ygZtBtp_JpuCw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTc1MA--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/tallahassee-democrat/baca478f26a907329532b0b248dbe10e)

Demolished in 1975, the baseball stadium on South Monroe Street, just down the hill from Gaines Street, was built to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Tallahassee in 1924.

Centennial Field was home to a Class D minor-league team, the Tallahassee Capitals, from 1935 to 1942 and from 1946 to 1950. A local semi-pro team, also called the Capitals, played there from 1946 to 1956.

Babe Ruth himself was even offered a job as Capitals manager, wrote Democrat writer Gerald Ensley in 2014.

“The Babe said no thanks,” Ensley said.

But on April 2, 1937, his former team, the New York Yankees, beat the Capitals 5-2 in an exhibition game at Centennial Field. The New York Giants, Chicago Cubs and Cleveland Indians also played exhibition games at Centennial Field.

Today, the field’s historical significance is commemorated near the corner of Bloxham Street and Monroe Street.

Not just a park, an art deco memorial

Before it was the city's crown jewel park, the Cascades area was part of Tallahassee’s historic downtown.

Three old buildings, called the Bloxham Annex, were built between 1936 to 1939, and were perfect examples of art deco construction. They were the last in Tallahassee before being demolished in 2018 to build a $150 million residential-retail-office complex called Cascades.

The Firestone Building, between Gadsden and Meridian streets, was once the Leon County Jail. It's the location of Leon County's last recorded lynching – in July 1937, two Black prisoners were taken from the new jail by four white men, taken east of town and fatally shot. Earlier victims were hanged from an oak whose branches cascaded in the old jail yard. Now, where the jail used to be, sits a memorial to Leon County's victims of lynching.

The architect of the jail, the Firestone Building, was Leo Elliott, a Tampa architect who became famous for many buildings throughout Florida. Elliott also was the architect for Tallahassee's Leon High, built in 1937. Both were built as part of the federal Works Progress Administration of the Great Depression, which put millions of unemployed people to work on public works projects.

Locals tried to save the buildings surrounding Cascades Park when development threatened, but the only one currently standing is the old health department; the Leon County Health Unit broke color barriers with its interracial staff and care to both Black and white residents.

In 2019, Cascades developer North American Properties updated the building with a new roof, repairs to interior damages and original flooring, new windows and a new coat of paint.

Althemese Barnes, a historian and founding director of the Riley House Center and Museum, said the segregated Health Unit bused Black children in for appointments on separate days from white children.

"It’s important to preserve the architectural style and integrity," she said in 2019, when the renovated building was unveiled. “That’s the way present and future generations will learn how things used to be and how did that change."

How Cascades Park was born

According to Ensley, the idea of Cascades Park was first broached in 1971.

The state built a half-size version in 1978. That park closed in 1989 when soil contamination was discovered and it became a brownfield.

"It took until 2006 for federal, state and city forces to remove the contamination and deed the park to the city. In 2010, construction started — and completion was advertised as a couple years away. It turned out to be four years," Ensley wrote.

"But the four years allowed officials to add things that were needed (a Smoky Hollow tribute), eliminate things that weren't (a grand entrance from South Monroe Street) and adjust things for effect and cost (the history panels on brick posts, rather than an iron fence, along Meridian Street). It allowed Blueprint 2000 to assemble committees of citizens to help them plan.

"And Blueprint brought home the project for $30 million — when it was originally estimated to cost $35 million."

"Yes, it took a long time. But look what we got," said Wayne Tedder, then director of Blueprint 2000 and today an assistant city manager. "We did it the right way. We got the community involved, we used the sales tax the way voters wanted us to.

"It was worth the wait."

Cascades Park is one of those places that protects and memorializes history while providing a place where everyone in our city can meet in the middle.

"You have to be proud that Tallahassee actually built one of its dreams," wrote Ensley in 2014.

This article is part of TLH 200: the Gerald Ensley Bicentennial Memorial Project. Throughout our city's 200th birthday, we'll be drawing on the Tallahassee Democrat columnist and historian's research as we re-examine Tallahassee history. Read more at tallahassee.com/tlh200. Email us topic suggestions at [email protected].

This article originally appeared on Tallahassee Democrat: Tallahassee Cascades: Waterfall to baseball field to park in 200 years