Can you rein in the president without weakening the presidency?

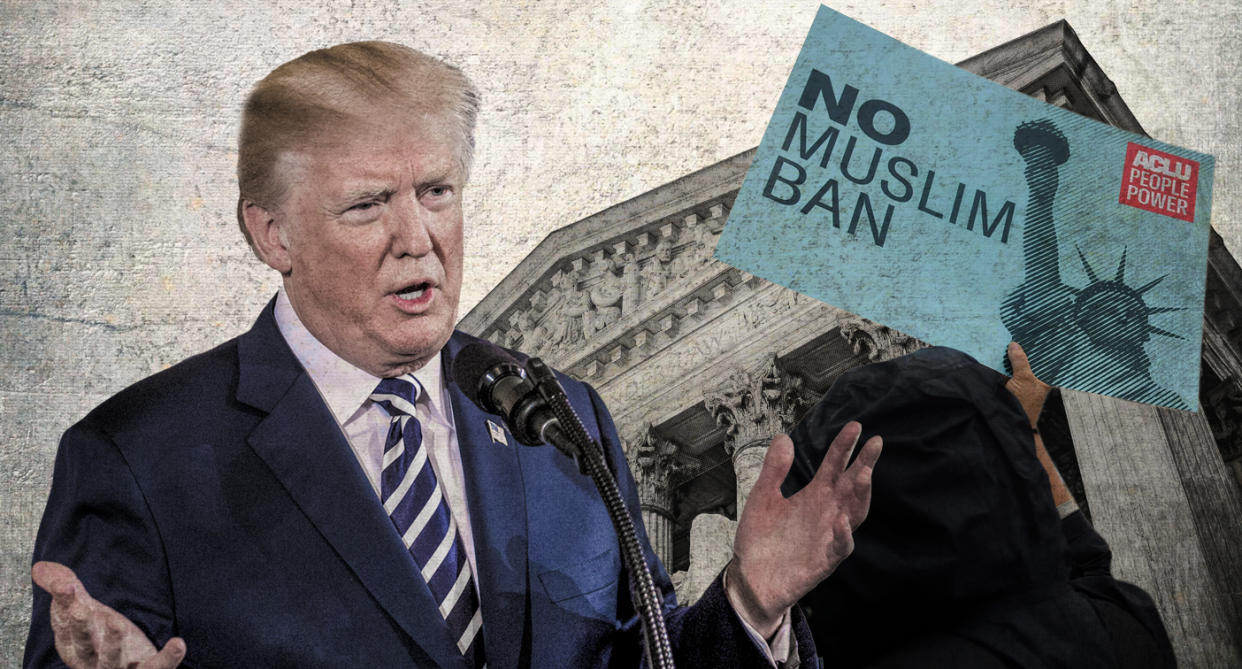

Having now heard arguments for and against President Trump’s immigration ban, the justices of the Supreme Court will have to weigh a couple of novel objections to the law.

One, summarized nicely in an op-ed this week by some of the elder statesmen in the president’s own party, holds that the Constitution clearly gives authority over immigration law to Congress, not the president, and that the court has an opportunity — if not an obligation — to restore the rightful balance of power between the two branches.

The second main indictment of the law rests on what the law calls “animus” toward a single religious group. In a brief supporting the state of Hawaii, which brought the case, more than 40 constitutional scholars argued that what matters here is Trump’s intent, made clear by his campaign rhetoric and his voluminous tweets from the Oval Office.

Trump seeks not to solve any real national security crisis, they say, but rather to stop Muslims from entering the country, period, which violates the very first amendment to the Constitution. (That amendment is already one of Trump’s least favorite, of course, since it contains that whole nettlesome thing about a free press, too.)

As a non-lawyer, I can’t weigh in with any authority on the technical validity of these arguments. As a critic of Trump’s odious proclamation — which I consider fundamentally un-American, legal or not — I’d certainly be relieved if the justices saw enough there to strike it down once and for all, which didn’t impress observers of the court as very likely.

But as someone who’s closely covered several presidential campaigns and administrations, I harbor some doubts about the logic of these objections, however noble the ends.

As with so much else about Trump, I worry that the inventive measures deployed to stop him might wind up weakening the presidency itself.

Both principal arguments here ask the high court to establish some new precedent on executive authority. The first point, about the separation of powers, is just the kind of argument that might appeal to conservative jurists, since it relies on a strict reading of the Constitution. But it also requires that the justices overlook decades of presidential action on immigration, as well as some long-standing case law.

The second line of attack is potentially even more consequential. Those who challenge the law on the basis of the establishment clause point out that the court has long enjoined Congress and state governments from enacting policies that are intended to discriminate against one group or another, even if the policy itself, in another context, might be lawful.

For instance, in the early 1990s, the City Council in Hialeah, Fla., reacting to the arrival of a church practicing the Caribbean rituals of Santeria, passed what seemed like a reasonable measure outlawing the possession of animals for sacrifice or slaughter. The Supreme Court ultimately invalidated the law, because its sole purpose was to thwart a single religious group from exercising its faith.

In the immigration case, the constitutional experts in their amicus brief cited numerous examples of Trump spewing hateful rhetoric, both before and after his election, as a way of justifying what he himself had called a ban on Muslims.

“The reason everyone thinks this policy targets Muslims,” Joshua Matz, a lawyer who co-authored the brief, told me recently, “is because the president has ostentatiously gone around saying it targets Muslims.”

He’s got a point. Except that the White House isn’t the Hialeah City Council, and this reasoning has never actually been applied to a president. (Largely because no modern president has done anything outrageous enough to test it.)

It’s not at all unusual — in fact, it’s the norm — for candidates and presidents to say whatever crazy stuff will rally their most ardent supporters to the cause, while doing something entirely more defensible when it comes to actually making policy.

In most presidencies, unfortunately, projecting defiance and even extremism while crafting more conventional law in private isn’t considered masking your true agenda. It’s what we call governing.

In this case, the administration rewrote its order twice in an effort to make the policy constitutionally viable — a process Trump complained bitterly had “watered down” his proposal. By Matz’s logic, however, Trump can’t actually do anything to restrict immigration that’s legally sound, because anything he tries to do has already been tainted by his own indiscreet blather.

Taken to its extreme, this means a president’s power can be curtailed by the presumption of motive, no matter what he or she might have proposed in terms of actual policy. Hypothetically, you can see how a president might be better off enacting sensitive policies without ever making a public case for them at all.

Trump’s critics would argue that this fear is specious, because Trump represents an extraordinary challenge to the norms of responsible governance, and as such the moment needs to be met with extraordinary measures. I get that, and no one would be happier to see him lose this fight than I would.

The danger, though, is that with each extraordinary measure they unleash, they risk permanently defining down the presidency. To use a sports metaphor, we’re not so much moving the goalposts on Trump as we are trying to bring in the sidelines, in order to shrink the field on which he can play.

Take, for instance, the congressional move to shield the special counsel, Robert Mueller, from being fired, which would give Congress rare purview over who stays and who goes in the executive branch. Precedents like that don’t go away once the crisis has passed.

The better option, as I’ve written, is to let Trump fire whomever he wants and have confidence that the voters will ultimately render a verdict. It’s their constitutional republic, after all.

Maybe the benefit here is pretty solidly worth the risk. Maybe you do what you have to do in the moment to contain an existential threat to American values, and you hope that the institution of the presidency will endure more or less as it has.

Were I a lawyer trying to win a case with grave implications, or a politician trying to cut short this presidency, that’s probably how I’d look at it.

But we can’t lose sight of the bigger picture here, which is that what Trump threatens to do — through his reality-show antics, through his alarming nepotism and incompetence — is to devalue the office and undermine our faith in the process.

It would be a real travesty to help him along.

Read more from Yahoo News: