California's Feinstein and Harris take aim at Trump's Supreme Court nominee

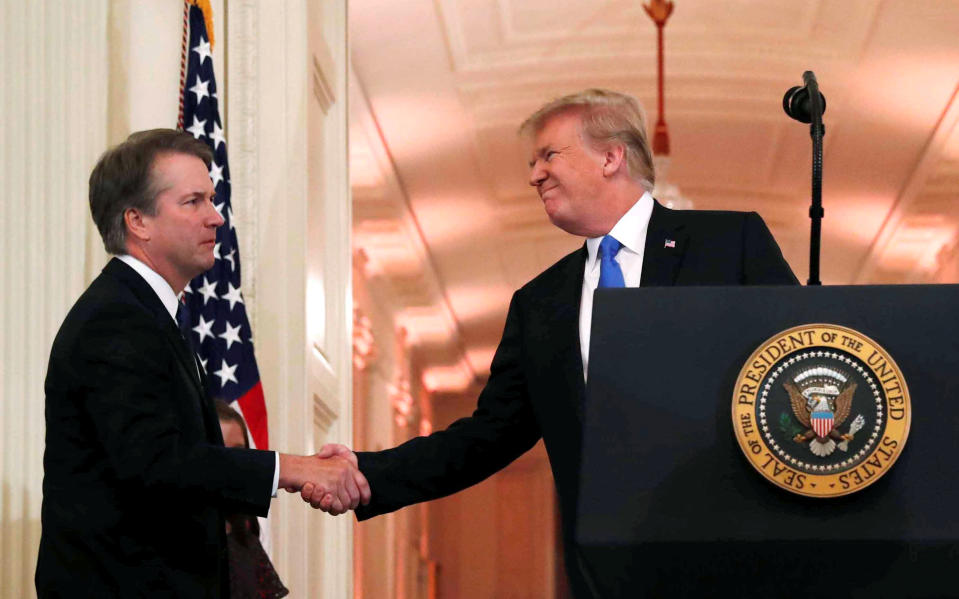

LOS ANGELES — As the confirmation hearings for Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh draw near, California’s two senators will have more power than any other Democrats to determine his fate — and highlight the challenges and choices facing the party as it struggles to chart a course out of the political wilderness.

Both Dianne Feinstein and Kamala Harris sit on the GOP-controlled Senate Judiciary Committee: Feinstein is the ranking member (i.e., the top Democrat); Harris is the junior-most Dem. As such, they are particularly well positioned to delay or derail Trump’s pick: Feinstein will lead the Democratic opposition and interrogate Kavanaugh first; Harris will question him last.

A lioness of Democratic politics, Feinstein, now 85, is the oldest sitting senator, and has represented the Golden State on Capitol Hill for the last quarter-century, becoming the only woman to chair the Senate Rules Committee and the Select Committee on Intelligence in the process.

At 53, Harris is one of the party’s freshest faces — a rising star who has gained a national following since arriving in Washington, D.C. last January.

Ultimately, Feinstein and Harris may not succeed in keeping Kavanaugh off the high court. Several red-state Democrats are considering supporting him as the seek to shore up their reelection chances, and neither of the two likeliest Republican defectors, Maine Sen. Susan Collins and Alaska Sen. Lisa Murkowski, have given any indication that they are, in fact, likely to defy the president.

But that doesn’t mean the Californians won’t try. For both, the political stakes couldn’t be higher. Feinstein, a relative moderate, is attempting to fend off a younger, more progressive Democrat, state Senator Kevin de León, 51, in the toughest reelection fight of her long career. (California elections are nonpartisan affairs, where the top-two primary finishers compete in the general even if they belong to the same party.) At the same time, Harris, boasting a diverse heritage and a fervent opposition to Donald Trump, is working to distinguish herself from potential rivals as she lays the groundwork for a possible 2020 presidential campaign. Both, in other words, have something to prove.

So, regardless of the eventual outcome, how Feinstein and Harris choose to approach the Kavanaugh hearings, and how other Democrats respond, will reveal a lot about where the party stands right now — and where it may be heading.

“Feinstein represents an approach that has dominated the Democratic Party since the onset of the Clinton era — a party of conciliation that prioritizes outreach to the political center and across party lines,” says Dan Schnur, a senior fellow at the USC Annenberg Center on Communication Leadership & Policy who previously served as a spokesman for Republicans John McCain and Pete Wilson. “That Democratic Party doesn’t really exist anymore. The party of Kamala Harris is much more combative.”

‘One million pieces of paper’

Last Saturday, Feinstein traveled to the Marriott City Center Hotel in Oakland, Calif., for a meeting of the executive committee of the state Democratic Party. During a breakfast that morning with supporters, she revealed her plan for the Kavanaugh hearings.

Prior to that moment, Feinstein hadn’t exactly been shy about criticizing Kavanaugh. The day President Trump announced his nomination, she’d released a statement warning that, if seated, Kavanaugh would be “pro-gun” and ensure that “Roe v. Wade would be overturned ‘automatically.’” (Her quotes referred back Trump’s campaign-trail promises about the staunchly conservative justices he would appoint.) Kavanaugh’s views “are far outside the legal mainstream,” Feinstein declared. “We need a nominee who understands that the court is there to protect the rights of all Americans, not just political interest groups and the powerful.” She also declined an invitation from the White House to watch the president reveal his pick in person.

But Saturday was different. For months, the California Democratic Party, which is dominated by progressives, had been open about its issues with Feinstein. After badmouthing her bipartisan instincts and relatively hawkish foreign policy views for years, activists became especially eager to unseat her when she refused last August to call for President Trump’s impeachment, arguing instead that he “can be a good president” if “he can learn and change.” De León has sought to capitalize on their unrest with his insurgent bid, and in February, delegates to the state party convention voted not to endorse Feinstein for a sixth term, awarding de León 54 percent of their support to Feinstein’s 37. The incumbent went on to defeat her challenger by 33 percentage points in the June 5 primary, but she’d come to Oakland, where the party would be issuing its general-election endorsements, to avoid a similar embarrassment.

The politics of the moment, then, were surely on Feinstein’s mind Saturday when she decided to get expansive about her Kavanaugh strategy. She reminded the crowd about her leadership position, saying she’d participated in 10 Supreme Court confirmation hearings and helped craft the party’s battle plan for contentious nomination fights. Yet this one, she predicted, would be “beyond — different from all of them.”

“The vetting process of this justice is going to be incredibly difficult,” Feinstein told her audience.

The reason, continued the senator, is that Kavanaugh generated “one million pieces of paper” during his decades-long career as a judge on the D.C. circuit court, a White House staff secretary under President George W. Bush, and an assistant to Kenneth Starr, the independent counsel who investigated President Bill Clinton — and “our staff is going to need to go through [all of them] prior to a hearing,” Feinstein said.

“We have a massive effort going,” she concluded. “We collect information from everywhere.

This strategy — rational, methodical and fastidious; a following of the facts wherever they might lead — should sound familiar to anyone who has observed Feinstein over the years. It’s perfectly in keeping with her measured approach to politics, which the New Yorker once described as “slightly formal in style,” with a faithful adherence “to procedure and protocol” and a belief in “settling disputes privately, by argument rather than by force.”

Feinstein has always avoided reflexive partisanship. In 1978, she became mayor of San Francisco after her predecessor, George Moscone, was shot and killed by a rival politician; it was a tumultuous, even violent time, and as the first woman to hold that office — as well as her previous position as president of the city’s board of supervisors — Feinstein was careful not to seem extreme. A member of the Judiciary Committee since 1993, she voted for several of Bush’s lower-court nominees and against filibustering Kavanaugh himself when Bush nominated him to the D.C. Circuit Court. She can also be tenacious in pursuit of what she believes is right. Perhaps the best example is her lonely, years-long war against the CIA and the Obama administration, both allies in other regards, over the issue of Bush-era waterboarding and torture — a clash that saw her and her staff immerse themselves in millions of documents and ultimately expose, with a 6,300-page report, the full extent of government wrongdoing.

“She’s absolutely not the type of person who’s going to be the first to make a partisan statement,” Hawaii Sen. Brian Schatz recently told Politico. “She’s a person who does her research, however long that may take.”

In other words, Feinstein is a realist — someone who thinks in terms of what is possible and works within the system to achieve it.

Feinstein’s realism explains why she is calling on Republicans to cooperate, in a “bipartisan” fashion, with her extensive document requests — just as she and other Democrats did when Republicans requested similar documents from Barack Obama nominee Elena Kagan, and despite Republican complaints that such transparency would delay Kavanaugh’s confirmation process. (That may be part of the point.)

It also explains why, when Feinstein outlined her endgame in Oakland, she stopped short of saying she would stop Kavanaugh. Rather, she explained that as “the lead Democrat of the committee” it’s “really key and critical” that she “put[s] together a kind of message” for “the American people” that will “enable” the “five Democratic [senators up for reelection] from states that Donald Trump won” by large margins to “vote along with” the rest of Democratic Party — a line of reasoning that implicitly acknowledges how daunting it will be to flip any Republicans, which is what Democrats need to do if they actually want to prevent Kavanaugh from becoming a Supreme Court justice.

In response, de León pounced, insisting at a different Oakland event that Feinstein & Co. “need to shut the Senate down” instead.

“Republicans go [for] the jugular all the time,” de León later told a reporter. “It’s time for Democrats to fight as hard for our values as conservatives fight for theirs.”

Later that day, the California Democratic Party endorsed de León with 65 percent of the vote.

‘A direct and fundamental threat’

Harris hasn’t said as much as Feinstein about the coming fight over Kavanaugh. But what she has said so far — and, more importantly, what she’s done in previous nomination battles — suggests that she will be approaching the hearings with a different goal in mind.

The instant Trump announced his pick, a combative Harris took to Twitter. “Judge Kavanaugh represents a direct and fundamental threat to the rights and health care of hundreds of millions of Americans,” Harris wrote. “I will oppose his nomination to the Supreme Court.” (In her initial remarks, Feinstein said nothing about how she would vote.)

Half an hour later, Harris was already casting this decision in personal terms, highlighting her own multi-ethnic background — her mother was Indian and her father was Jamaican — to explain why the composition of the Supreme Court is so important.

“Two decades after Brown v. Board, I was only the second class to integrate at Berkeley public schools,” Harris added on Twitter. “Without that decision, I likely would not have become a lawyer and eventually be elected a senator from California. That’s the power a Supreme Court justice holds.”

And when Harris spoke to PBS’s Judy Woodruff the following day, she admitted that while she was “in the possess of reviewing [Kavanaugh’s] writings and his background in terms of the decisions he’s made and the speeches he’s given,” she already had a pretty good idea of the questions she wanted to ask him.

“I will definitely ask him about whether he believes that Roe v. Wade is settled law,” she said. “It is also important to also know how he feels about issues like same-sex marriage and whether he believes that marriage is a fundamental right that should be guaranteed to all people. [And] there are questions I have about where he stands on issues like discrimination, be it against members of the LGBTQ community or based on race [or] religion.”

Unlike Feinstein, Harris didn’t focus on how she would be digging through millions of documents, potentially delaying Kavanaugh’s confirmations as she searches for some nugget that could convince other Democrats to vote against him. Unlike de León, Harris never mentioned anything about using arcane parliamentary tactics to shut down the Senate. (Perhaps that’s because, as a someone who’s actually in office and not just running for it, she knows they ultimately wouldn’t work.)

What Harris did do, however, is exactly what has made her such a brand name among Democrats in such a relatively short period of time: Resist Trump in the strongest possible terms, make it personal and seize center stage.

Harris is a career prosecutor: first a deputy district attorney in Alameda County, Calif., then San Francisco district attorney, then attorney general of California. She is expert at grilling people in public — and that’s the primary way she has raised her profile in the Senate. Last June, Harris asked Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein whether he’d reinstate a Bush-era special prosecutor policy that would prevent Trump from firing special counsel Robert Mueller; when Rosenstein tried to filibuster, she repeatedly demanded a yes or no answer. A week later, Harris asked Attorney General Jeff Sessions to explain the legal basis for refusing to answer questions about his communications with Trump. Both times Harris dismissed their dodges and doggedly kept asking the same question; both times, she was shushed by Republicans on the committee.

The confrontations made a splash, and progressives praised Harris for her persistence. So she kept it up. This April, Harris forced Facebook head Mark Zuckerberg to contradict himself several times about why the company did not inform tens of millions of users in 2015 that their data had been improperly sold; in May, she asked soon-to-be CIA Director Gina Haspel whether Bush-era techniques for interrogating terror suspects were immoral. Haspel deflected.

“Answer yes or no,” Harris shot back.

Again Haspel tried to avoid the question, and again Harris interrupted. “Please answer, yes or no,” she said. “Do you believe in hindsight that those techniques were immoral?”

Another non-answer, another curt Harris interruption. Finally, Haspel said, “Senator, I think I’ve answered the question.”

“No, you’ve not,” Harris snapped.

Expect more of this from Harris in the Kavanaugh hearings. According to her staff, Harris spends extensive time preparing for hearings like these, looking to use her experience as a career prosecutor to question Kavanaugh.

As the last Democrat to interrogate him, she can zero in on subjects that have been insufficiently covered by her colleagues and act as a “closer” of sorts, asking questions multiple times to try to pin him down on subjects he’s tried to avoid.

The question for Harris is whether such tenacity can actually change anything. Rosenstein, Sessions, Zuckerberg and Haspel were tripped up but not derailed because of her cross-examinations (though Arizona Republican Sen. John McCain did allude to Harris’s line of questioning when he announced his opposition to Haspel’s nomination, saying, “Her refusal to acknowledge torture’s immorality is disqualifying.”) And regardless of how many times Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer insists that Kavanaugh has a “serious and solemn obligation” to share his “personal views” instead of resorting to the boilerplate evasions employed by past Supreme Court nominees — avoiding the question of whether they’re anti-abortion or pro-abortion rights by insisting that they will respect “precedent” and defer to “settled law” — Kavanaugh, one of the top legal minds of his generation, is unlikely to cough up damaging information just because Harris gives him the third degree.

The more likely outcome? Harris, who just inked a book deal, enjoys another round in the spotlight. Progressives praise her again. And the 2020 talk ramps up.

With hearings not expected to begin until early September, it’s impossible to know which approach will play a bigger part in the Democratic Party’s long-shot campaign to keep Kavanaugh from the high court. Conceivably, Feinstein’s quiet, methodical pragmatism could produce a revelation that would upend the hearings; that may be easier to imagine, in the end, than Harris tying Kavanaugh in knots and forcing him to self-incriminate.

Or it may be that the Californians work in tandem, with Feinstein providing institutional expertise on process and procedure and Harris using her prosecutorial skills and newness in Washington to find avenues of opposition not dictated by previous norms.

Either way, as Schnur points out, “these hearings may ultimately be less about preventing Kavanaugh’s confirmation” — again, a long shot — “than about positioning the Democratic Party to take maximum political advantage of it in November.”

In that sense, the question facing Democrats is whether the political realism that defined the party under Bill Clinton, Barack Obama and Dianne Feinstein still packs a punch — or whether, in the Age of Trump, something more pugnacious is now taking its place.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

Ex-NSA official: Russian hack of Democrats was ‘assembly line operation’

Brett Kavanaugh’s ex-boss: It’s ‘preposterous’ to demand his recusal from Mueller cases

‘I thought I would never see him’: Asylum seeker and son reunite after border separation

After Trump’s defense of Putin, sighs of resignation — but nobody’s resigning (yet)

Trump and Putin: The admiration is mutual, the benefits one-sided