Browns learn of 'forgotten' players at Hall of Fame tour

CANTON, Ohio (AP) — The Cleveland Browns went on a field trip to explore their football roots, including some deep ones nearly forgotten.

Hoping to connect his team to its storied past, Cleveland coach Kevin Stefanski took minicamp on the road Wednesday with a trip south to Canton for a light practice along with a tour of the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

“It’s important honestly for all of us in any walk of life to know the people who walked that path before you,” Stefanski said. “My job as the head coach of the Cleveland Browns is finite. I will not have this role forever. I know people have come before me. I know there will be people who come after me.”

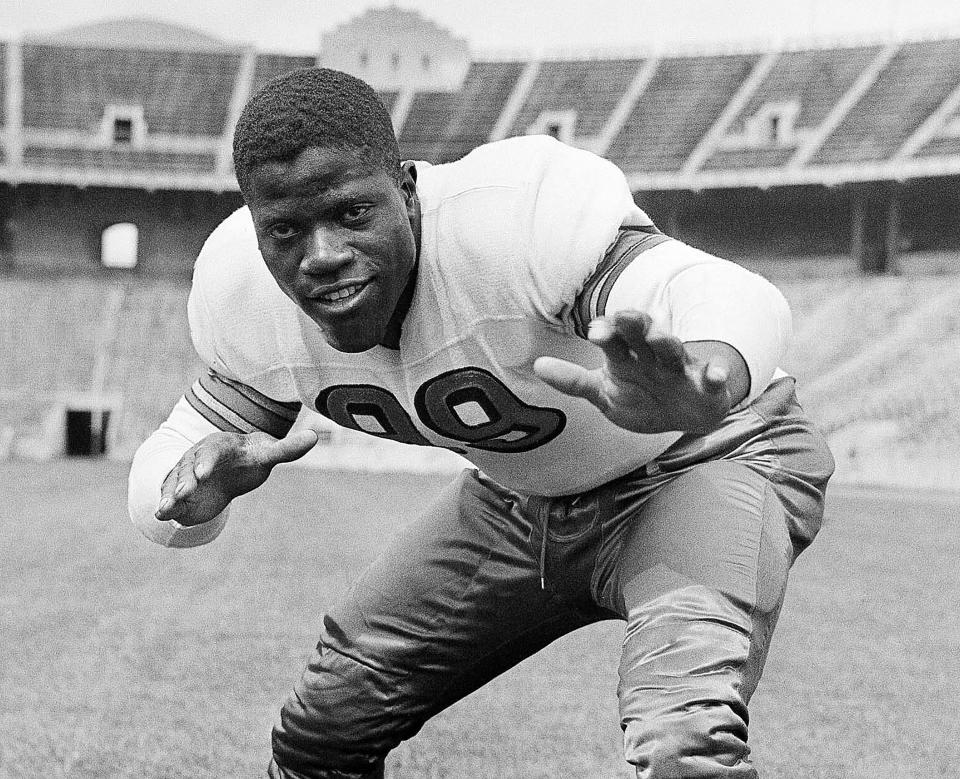

Before walking amongst the bronze busts of enshrined players, quarterback Deshaun Watson, star running back Nick Chubb and their teammates listened to a presentation about Browns Hall of Famers Bill Willis and Marion Motley, who along with Kenny Washington and Woody Strode broke pro football’s color barrier in the 1940s.

Known as the “Forgotten First,” the quartet of Black players helped end NFL segregation, a shameful period from 1933-46 rarely acknowledged by a league that takes pride in its generational legacy.

“They stepped up,” said Willis' son, Clem, who spoke along with his brother, Bill Jr. and Motley's grandson, Tony. “They put their lives on the line and sacrificed to make a better place for themselves and their people.”

For more than 30 minutes, the Browns heard riveting stories about Willis and Motley, whose bravery has been chronicled in a book co-authored by former NFL wide receiver Keyshawn Johnson and longtime football writer Bob Glauber.

Growing up in Los Angeles, Johnson was familiar with Jackie Robinson, who pioneered baseball's integration.

However, he knew nothing of pro football's own troubling racist history.

“We were only going to be taught what they wanted to teach us,” said Johnson, the 1996 No. 1 overall pick who played 11 seasons in the league. “When I first learned this, I was like, ‘How could this possibly be? How could these individuals be such all-stars within our community and we know nothing about them?'

“It's almost like it was a secret.”

A phone call from Glauber a few years back prompted Johnson to get behind the project "so younger players knew who laid the foundation and where it came from,” especially in a league in which 70% of the players are Black.

In 1946, Browns coach Paul Brown signed Willis and Motley, who became the first Black players in the All-America Football Conference. The same year, Washington and Strode got contracts with the Los Angeles Rams, who formerly played in Cleveland and busted the NFL's whites-only barrier.

The four men were subjected to verbal attacks, vicious hits after the whistle and even death threats.

But for years, they were barely football footnotes.

Glauber emphasized the point by asking any of the Browns players to raise their hands if they had heard of Willis, Motley, Washington and Strode before coming to Cleveland. Only a few went up. He didn't know about them, either.

“I was embarrassed, honestly,” said Glauber, who writes for Newsday. “Then I realized if I don't know this, Keyshawn doesn't know it, this story needs to be told.”

Stefanski wanted his players to hear it as well.

After boarding five charter buses in Berea, the team's players, coaches and support staff made the one-hour drive, which became a journey back through the team's glory years. On the way, players watched a documentary on legendary running back Jim Brown, one of 22 Cleveland players immortalized in the hall.

All-Pro left guard Joel Bitonio admitted not knowing much about the Browns' history before he was drafted in 2014.

“You kind of look back and it was like before the Super Bowl era,” Bitonio said. "I mean 17 Hall of Famers, multiple championships, some of the best players to ever play the game, innovators, some of the best coaches to ever (coach) the game have come through here.

“You kind of get a respect of why the Browns fans are the way they are.”

Stefanski respected Browns superstar defensive end Myles Garrett's wishes and excused him from the tour. Last week, Garrett said he didn't want to visit the museum until he's being enshrined.

“I understand his feelings on that,” Stefanski said before the tour.

Linebacker Anthony Walker Jr. wasn't surprised by Garrett's request.

“I know if you play this game you want to be the best at it,” he said. “And if you don’t have that mindset then you’re not going to last very long in this league so for him to set them goals, I mean, I expect nothing else from him. It’s kind of early right now, but I say he’s a shoo-in.”

NOTES: The team will practice at FirstEnergy Stadium on Thursday to conclude their mandatory minicamp. ... WR Anthony Schwartz was sick and didn't make the trip to Canton.

___

More AP NFL coverage: https://apnews.com/hub/NFL and https://twitter.com/AP_NFL