Birds on the brink: Audubon, birders banding together to save RI's birds

NEWPORT — The Eastern Towhee is a sparrow that doesn’t look like a typical sparrow. With its ink-black hood and sepia sides, the male especially stands out in the landscape.

But it’s getting harder to spot the towhee or hear its distinctive “chewink” calls in Rhode Island and elsewhere across its range in the eastern half of the country. The bird’s numbers have plummeted by half in the last 50 years or so.

It’s an all-too-familiar story playing out with countless species in the avian world. Over the same time period, North America has lost nearly 3 billion birds – 30% of the total population.

It was against this backdrop that 200 people came out to Newport on Sunday for the Audubon Society of Rhode Island’s second annual Birds Across New England symposium.

“There’s a very real need to bring these species back,” said Charles Clarkson, director of avian research for Audubon of Rhode Island.

Educating the public about bird losses in bid to drive conservation

Doing that will mean getting the word out about the plight of birds and motivating the public to do something about it, he said.

That was the very reason for the symposium on Sunday. By connecting people in the scientific community with everyday bird enthusiasts, the hope is that the nation can start to turn the tide on the decline of avian species.

Audubon has stepped up its efforts in this regard in recent years. It started with hiring Clarkson after he finished coordinating the research and writing that went into “The Second Atlas of Breeding Birds in Rhode Island.” The five-year project was capped with publication last year of the 480-page atlas, which is the authority on what birds are found in the state and where.

More: Dozens of birds will be renamed in the next few years. These RI birds are on the list.

Clarkson followed up with a similar study for the birds found on 9,500 acres of Audubon’s holdings in Rhode Island and Massachusetts. The findings weren’t encouraging. More than a third of birds that breed in the organization’s 14 refuges are in decline.

But the hope is that by better understanding what types of habitats are most valuable, Audubon and other stewards of wild lands can do more to manage or expand them.

Towhees, warblers and whip-poor-wills

The study named nine so-called “responsibility birds” in need of conservation. They’re species that are still relatively abundant and can be helped through some type of human intervention, like carving out more of the habitats they need. They’re also birds seen as umbrella species, meaning the help they receive will benefit other bird types.

The Eastern Towhee is one of them. The species was found throughout Rhode Island during research for the new bird atlas, but its numbers across New England have been dropping by more than 4% a year for the last 50 years. While researchers could rely on finding dozens of towhees on surveys in past decades, now they’re counting just one or two, said Clarkson.

“We’re working hard to understand what the primary drivers of decline here in Rhode Island are and what we can do to bring the population back,” he said.

To that end, University of Rhode Island graduate student Megan Gray has been studying the towhee, as well as the prairie warbler, another of Audubon’s responsibility birds, to determine the connection between the quality of their habitat with nesting success.

Both species are in trouble because they prefer areas of shrubs and saplings along the edges of woodlands, a type of habitat that’s declining as forests mature and as natural disturbances like wildfires are better controlled. In places like the Big River Management Area in West Greenwich, the state Department of Environmental Management has cut back parts of the forest to create what’s known as early successional habitat.

While Gray has yet to reach any conclusions in her study, she said one thing appears clear:

“More early successional habitat will not go to waste,” she said.

The same habitat also benefits the Eastern Whip-poor-will, an expertly-camouflaged nightjar whose eponymous song can be heard on moonlit summer nights. The species, too, is losing numbers, but habitat restoration is helping, said Liam Corcoran, a URI graduate student whose research is focused on the whip-poor-will.

“It appears that species who prefer these habitat types are using them,” Corcoran said of the efforts in Big River and the Great Swamp Management Area in South Kingstown.

There's still hope to save bird species

If there’s hope for these birds, it can be found in conservation efforts that have saved other birds. Ospreys were once decimated by the widespread use of DDT, a now-illegal pesticide that leached into waterways, made its way into fish, and damaged egg production.

When the DEM first started tracking osprey nests in Rhode Island in 1977, there were only nine active nests. Last year, volunteers with Audubon, which took over the monitoring program, counted 251, according to Lincoln Dark, who manages the program.

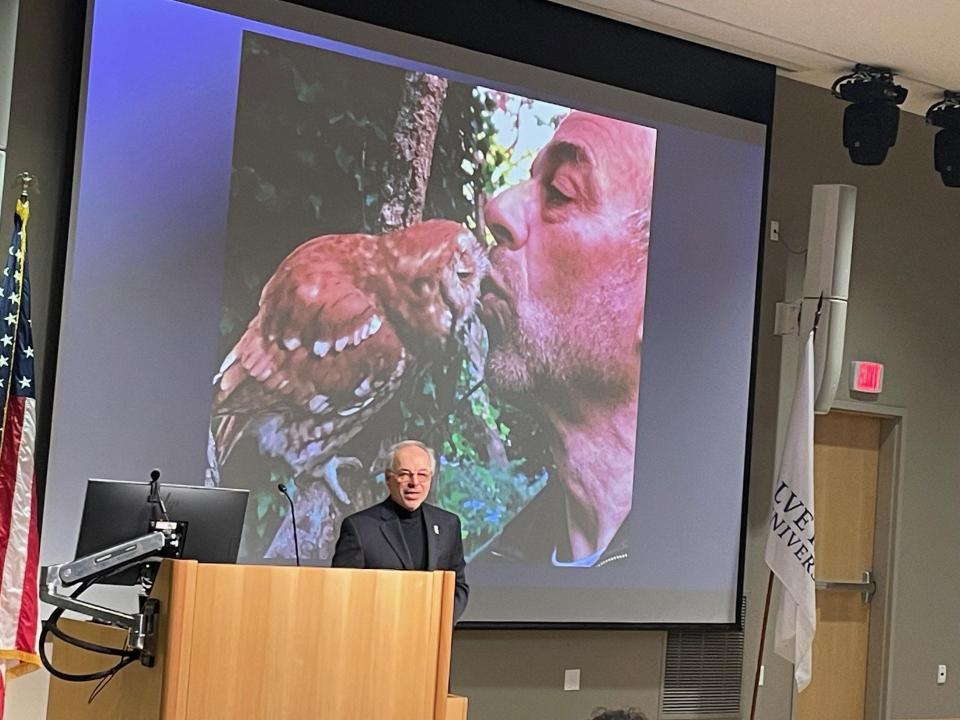

Ecologist Carl Safina, who delivered the keynote address at the symposium, spoke about an owlet he rehabilitated and the connection he made with the little bird he named Alfie. He said such up-close experiences with nature are needed for people to start working toward change.

“Alfie taught me that even owls have a word for love and that if we care to connect, we can take those connections wherever we go,” he said.

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Audubon sounds the alarm on decline in RI's bird populations