Biden turned to a wartime power his first day in office. Will he rely on it even more?

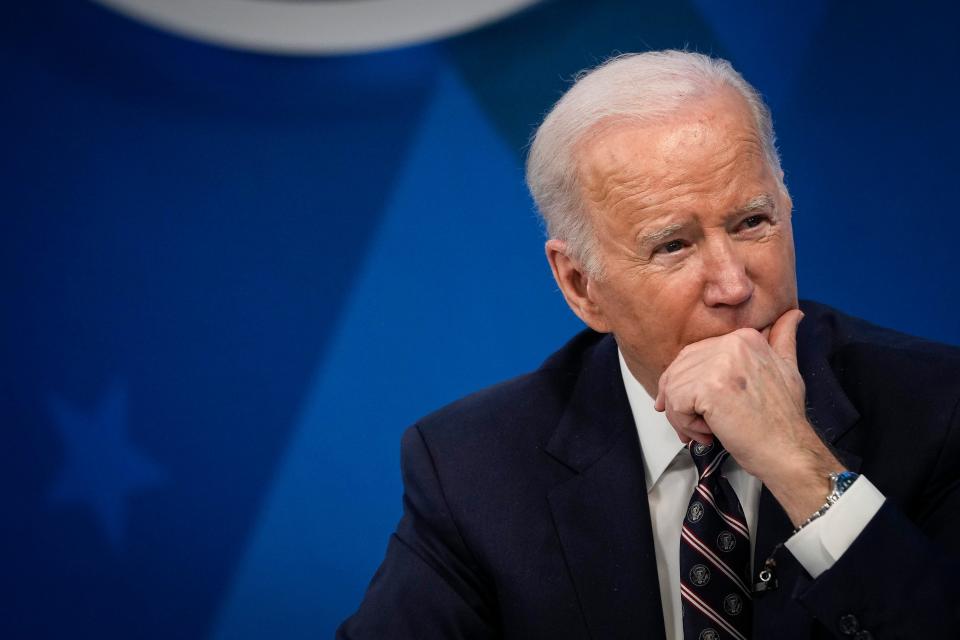

On his first full day in office, President Joe Biden took advantage of a special, wartime power to supercharge the U.S. pandemic response, using a tool he would return to multiple times throughout his presidency.

In an executive order citing authority under the Defense Production Act, the new president directed his administration to secure masks, tests and other equipment in short supply. Biden soon ordered a 100-day White House review of American industry that concluded the act was a “powerful tool” that could be deployed beyond the pandemic and traditional military use.

Biden went on to issue a series of orders relying on the act – to jumpstart mining of minerals for electric car batteries in March and to increase baby formula supplies in May. In June, he invoked the act in orders authorizing federal investment in manufacturing of solar panel components, insulation, electrical transformers and heat pumps, part of a broader effort to combat climate change.

How Biden and other presidents used the DPA: Baby formula, body armor, biofuel

Experts say his use of the act is notable, given the number of times he’s invoked it and for such a wide range of reasons. The Korean War-era law gives presidents the power to require and pay private companies to help during war and national emergencies, but, “Biden, since he's been elected has really used it in a very vigorous fashion,” University of Maryland law professor Michael Greenberger said.

Biden’s exercising of the unilateral power has also drawn criticism that he has twisted the act beyond its intent to advance his political agenda and, at times, to compensate for administration oversights. On baby formula, the Food and Drug Administration failed to adequately prepare for the closure of a key factory, which sent parents across the country scrambling to feed their babies.

“He's a frustrated person,” said Erik Gordon, a University of Michigan professor who specializes in economics and law and has written on the DPA.

Biden’s approval has been underwater since last summer – with more Americans disapproving than approving of the job he’s doing as president, according to FiveThirtyEight, which tracks polling averages. A USA TODAY/Suffolk Poll in June found his approval rating had dropped to 39% amid economic fears.

White House spokesman Abdullah Hasan said the president has used the Defense Production Act to take “decisive actions” that “have and continue to deliver results."

“The President is committed to using every lever at his disposal to address the challenges facing American families,” Hasan said in a statement. "He has not hesitated to invoke the Defense Production Act where it is appropriate and within his authority to do so.”

Now, even if Congress passes recently announced climate legislation, there is much left to do in his agenda, including on immigration and climate. Biden has raised the notion of using executive authority again, as he warned when earlier climate talks collapsed.

If Republicans win big in midterm elections this fall, as political analysts predict, Biden will face increasing difficulty moving his agenda through Congress, potentially forcing him to rely on the act even more to enact priorities key to his reelection hopes in 2024.

Bush, Obama sped military gear, Trump kept meat plants open

The Defense Production Act was passed in 1950 during the Korean War and gives the president power to order private industry to prioritize and produce goods needed for national defense, such as steel needed for warships and munitions. The scope of the act has been expanded over the years to include emergency preparedness and recovery from national disasters.

Presidents have broad discretion over when to use the power. The law requires them to make a determination that materials are essential for national defense or emergencies, though presidents have the power to waive that requirement as well.

Presidents from both parties have invoked the act for the military. Under President George W. Bush, the Pentagon used his authority under the law to order companies to make body armor to outfit troops in Iraq after thousands had been deployed without it.

Under Obama, defense officials used the law to speed up production of mine-resistant vehicles designed for the rugged terrain of Afghanistan. Some 5,700 were delivered to the battlefield within a year, administration officials said at the time.

Presidents also have relied on the law to help with recovery after natural disasters. The Bush administration used it to restore rail service and accelerate construction of flood walls and other infrastructure in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina devastated the Gulf Coast in 2005.

Trump and Biden both employed powers under the act to respond to the pandemic. Trump was criticized for not using them soon enough to force companies to make ventilators and other equipment during the initial onset of COVID-19 in 2020. He said ordering private industry to make products would amount to “nationalizing” businesses. But Trump later relied on the act to order General Motors to make thousands of ventilators.

He also invoked it to help keep meat and poultry processing plants operating despite outbreaks among workers. After entreaties from industry executives, Trump designated meat and poultry critical and strategic materials and said he wanted to ensure "a continued supply of protein for Americans." USA TODAY reported thousands of meatpacking workers contracted the virus during the first year of the pandemic and more than 200 died.

Biden administration: DPA is a 'powerful tool'

Barely a month after taking office, Biden ordered a comprehensive 100-day review of U.S. supply chains, whose vulnerabilities had been laid bare during the pandemic and severe weather events – like the winter storm in February 2021 that left hundreds dead and millions without power in Texas.

The resulting report laid out what it called a “new approach” to revitalize the U.S. industrial base to ensure national and economic security and included recommendations that Congress provide funding to key industries, including semiconductor and battery cell manufacturing. It also said the administration should deploy the Defense Production Act.

“The DPA has been a powerful tool to expand production of supplies needed to combat the COVID-19 pandemic, and has been used for years to strengthen Department of Defense supply chains,” the report concludes. “The DPA has the potential to support investment in other critical sectors and enable industry and government to collaborate more effectively.”

With COVID, Biden used the act to speed up vaccine production, increase the supply of COVID-19 tests, and produce personal protective equipment and other medical supplies. The president then branched out into other areas.

After hopes had withered that Congress would pass Biden’s sweeping climate legislation, the White House said the president was prepared to take action on his own and announced in March that Biden would issue an order under the Defense Production Act to boost domestic production of minerals used to make electric car batteries.

He turned to the law again in June, issuing a series of orders authorizing federal investment in domestic manufacturing of parts used in solar panels, as well as transformers for the electrical grid and heat pumps and insulation, which improve energy efficiency in buildings.

The White House, when asked what solar emergency necessitated invocation of the wartime powers, said the orders would strengthen the power grid and help tackle the climate crisis.

"This is a very important part of the president’s agenda in getting to that clean energy system that he’s been talking about since he walked into the administration," Press Secretary Karine Jean-Pierre said at the time. "This is particularly urgent given the impact of Russia’s invasion in Ukraine on the global energy supply, as well as the intensifying – the impacts of climate change on the electricity grid."

But experts and lawmakers criticized the orders as a fix for his administration's shortfalls and an end-run around Congress, which stonewalled sweeping climate legislation for months.

“I was in the army 36 years and I never saw a heat pump out on the battlefield,” said retired Lt. Gen. Thomas Spoehr, director of the Center for National Defense at the conservative Heritage Foundation. “Just to say some of these things like insulation and solar panels and heat pumps are critical to the national defense – It's quite the leap, I think.”

He and other experts say such orders can lead to millions of tax dollars being spent without congressional approval on projects with political benefits but not solutions to immediate emergency needs as envisioned under the Defense Production Act.

“In my view, that's not a good use, a proper use of the DPA because it basically gives the president a lot of money to use, as he or she wishes,” said Tyler Priest, a historian at the University of Iowa who specializes in energy and environmental policy and has studied presidents' use of DPA.

Previous DPA energy projects come up short

President Jimmy Carter invoked the act in 1980 to provide “immediate financial aid” to jumpstart production of synthetic fuel during his reelection bid, which had been beset by an ailing economy reeling from sky-high inflation and soaring gas prices. He lost reelection, and the effort ultimately crumbled after oil supplies increased and prices dropped.

The Obama administration used the act to invest more than $200 million to build biofuel facilities. The White House hailed the investment in 2014 as “important progress” on President Barack Obama’s climate agenda and said three companies would construct the facilities. One would convert garbage to fuel, another would use wood cuttings, and a third would use fat and grease. The plants would be operational in 2016 and produce upwards of 100 million gallons of fuel at prices competitive to gas, the Department of Energy said at the time.

As of this month, none has produced any biofuel, a USA TODAY review found.

Obama at the time had dubbed his approach to the presidency the “pen-and-phone” strategy, saying he would sign executive orders and call people to accomplish his agenda since Republicans were blocking it in Congress.

Priest said the problem with using the Defense Production Act to address climate change is that it’s not a short-term emergency, it’s a gradual, long-term crisis that requires solutions that can’t be repealed by the next president or defunded by Congress – like orders using the DPA.

“But it's hard to get any kind of bipartisan consensus to pass any kind of legislation to address climate change,” he said. “So Democratic administrations – the last two Democratic administrations – are trying to find creative ways to use existing statutes and authorities.”

Biden knocked for 'political theater' on DPA

Critics latched on to Biden’s use of the act in May to crank up supplies of baby formula. The FDA had failed to act quickly enough to address shortages when the nation’s largest manufacturer, Abbott Nutrition, shut down a Michigan plant in February. Empty store shelves sent parents on a frantic search for formula. Malnourished infants were hospitalized.

Biden announced in May that he was using powers under the Defense Production Act to speed up delivery of baby formula ingredients to manufacturers.

But Peter Pitts, a former associate commissioner at the FDA under George W. Bush, said the crisis was caused by a factory shutdown, not a lack of ingredients such as corn syrup and rice starch, commodities that are available in abundance.

“It’s political theater,” Pitts said of Biden’s DPA order.

The White House said the president's order allowed formula manufacturers to increase production by as much as a third.

"His decisive actions, including in response to a critical need for COVID-19 tools or a baby formula shortage because Abbott shut down its facility, have and continue to deliver results,” spokesman Abdullah Hasan said.

Some of the orders, such as the one on formula, didn't cost anything, the White House contended, and others authorized federal spending from a pot of money that Congress approved for emergency uses under the act – so technically lawmakers approved its spending.

'This is a power struggle'

Deborah Pearlstein, co-director of the Floersheimer Center for Constitutional Democracy at Cardozo School of Law at Yeshiva University, said Biden’s use of the act is not an end-run around Congress since Congress passed the law in 1950 to give presidents the authority in the first place.

She said the worry in the use of broad laws like the Defense Production Act is that a president would invent a pretext to do something not in the public interest or something he doesn’t have the authority to do otherwise. Pearlstein said Trump declaring a national emergency to fund construction of the border wall qualified as a worrisome use of one such law, but Biden’s reliance on the Defense Production Act does not.

“I think this is an expansive but lawful use of a broad delegation of legislative authority,” she said.

Gordon, the University of Michigan professor, said presidents have continued to expand use of the act for decades.

“I think what you're seeing is presidents want to have more power, and Congress is often not cooperative,” he said. “So this is a power struggle.”

Contributing: Rachel Looker

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Biden's prolific use of Defense Production Act is notable, experts say