Biden looks to overturn Trump's undoing of Obama's foreign policy legacy, but Iraq remains a question mark

Presidential elections are decided by many things: media exposure, financial backing, personal chemistry, timing and luck. Policy positions often are just a way of signaling where a candidate stands on the political spectrum. But 2020 is shaping up to be different, the most ideas-driven election in recent American history. On the Democratic side, a robust debate about inequality has given rise to ambitious proposals to redress the imbalance in Americans’ economic situations. Candidates are churning out positions on banking regulation, antitrust law and the future effects of artificial intelligence. The Green New Deal is spurring debate on the crucial issue of climate change, which could also play a role in a possible Republican challenge to Donald Trump.

Yahoo News will be examining these and other policy questions in “The Ideas Election” — a series of articles on how candidates are defining and addressing the most important issues facing the United States as it prepares to enter a new decade.

Since he became president, Donald Trump has seemed singularly focused on undoing the accomplishments of his predecessor, Barack Obama, especially when it comes to foreign policy. He withdrew the United States from the Paris Agreement on climate change, the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade pact and the Iran nuclear deal — all key Obama-era policies. In turn, when the 2020 candidates for the Democratic presidential nomination talk about foreign policy, they’ve promised to overturn Trump’s own legacy.

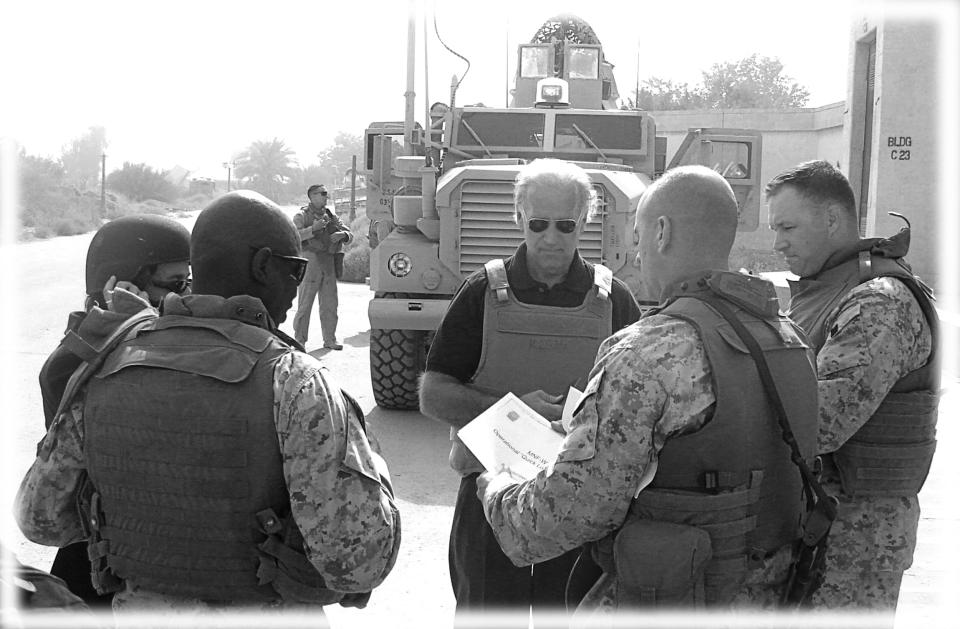

Former Vice President Joe Biden easily outmatches his opponents in foreign policy experience. He served 12 years as chairman or ranking member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. When he became vice president, Biden closely advised Obama on Middle East policy and oversaw the withdrawal of U.S troops from Iraq.

In a major speech on foreign policy last week, Biden detailed how he would restore America’s position as a global leader. He talked about Afghanistan, China, Russia, climate change and global democracy. What he didn’t mention was Iraq, a potential point of weakness, should Biden win the nomination and face Trump in the general election, considering he authorized the U.S. military strikes under then-President George W. Bush.

Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., was a vocal opponent of the vote that paved the way for the invasion of Iraq. During the first Democratic debate of the 2020 race, Sanders criticized Biden’s vote, and the issue is sure to surface throughout the primary. Like Biden himself, 2020 contenders Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., and South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg have said the Iraq War was a mistake.

Trump, who parted ways with much of the Republican Party by criticizing the Iraq War, is sure to try to keep foreign policy debates centered on that conflict rather than his unwavering support for Saudi Arabia despite the killing of journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

Robert Gates, secretary of defense under George W. Bush and Obama, wrote a scathing review of Biden’s stances on foreign policy in his 2014 book “Duty: Memoirs of a Secretary at War.”

"I think he has been wrong on nearly every major foreign policy and national security issue over the past four decades,” Gates wrote.

In 1991, Biden voted against the Persian Gulf War, which ultimately pushed Iraqi forces from Kuwait. He opposed the war because he believed the anti-Iraq coalition placed the highest burden on the U.S.

As chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in 2002, Biden agreed with the Bush administration’s stance that Iraq and its leader, Saddam Hussein, possessed weapons of mass destruction.

“One thing is clear: These weapons must be dislodged from Saddam, or Saddam must be dislodged from power,” Biden said at a committee hearing in 2002. “If we wait for the danger from Saddam to become clear, it could be too late.”

Biden voted in 2002 to authorize the U.S. invasion of Iraq, a decision that has now been attacked by his rivals and critics. In the month leading up to the vote, Biden supported a Senate resolution that would have delayed the invasion until the United Nations passed a resolution determining whether to disarm Iraq peacefully or with force. His efforts were overruled by Democratic House Minority Leader Dick Gephardt, who supported a resolution with few restraints on the Bush administration.

Biden ultimately caved and supported the House resolution. On the Senate floor in 2002, he said he would vote for the authorization because it would put greater pressure on Saddam to allow inspectors into the country. This, Biden argued, would actually decrease the likelihood of war.

“I do not believe this is a rush to war,” Biden said then. “I believe it is a march to peace and security.”

There was no peace. As the U.S. struggled to stabilize Iraq, Biden declared in a 2005 interview that the war was a mistake. He claimed that the Bush administration misused Congress’s war authorization.

A year later, he proposed a plan to split Iraq into three autonomous regions for Sunnis, Shiites and Kurds. The idea was to save Iraq by decentralizing its government, but the plan was quickly rejected as undermining the Bush administration’s efforts to stabilize the country. Polls conducted in Iraq showed that the proposal was deeply unpopular.

Obama made withdrawing troops from Iraq a signature campaign promise during the 2008 election. Once elected, he entrusted Biden to oversee the withdrawal of 150,000 U.S. troops, which was completed in 2011. Four years later, however, the Islamic State took control of 40 percent of Iraq. Obama sent hundreds of troops to Iraq, and some remain there eight years later.

Other foreign policy decisions of Biden’s have been less controversial. In 1999, he helped expand NATO to include former Warsaw Pact countries, and he supported U.S. intervention in a civil war in the Balkans. Biden also tried unsuccessfully to convince Obama not to send more troops to Afghanistan in 2009.

At the City University of New York last week, Biden laid out a detailed vision for U.S. diplomacy that he said will restore America’s standing as a world leader. He pledged to rejoin both the Paris Agreement on climate change and the Iran nuclear deal and vowed to resume funding to Central America that Trump has cut.

Biden has also pledged to lift the current travel ban on seven Muslim-majority countries and stop the practice of separating migrant children from their parents. He has also campaigned on a promise to end the Trump administration’s “detrimental asylum policies and raise our target for refugee admissions.”

Several of Biden’s rivals have made similar pledges about the Paris Agreement and travel ban, portraying themselves as a foil to Trump’s erratic foreign policy. Biden presents himself as the presidential candidate who can fix it all, and he often cites his experience with foreign affairs as a major asset.

“The threat that I believe President Trump poses to our national security and where we are as a country is extreme, and I don’t think we can afford to ignore it,” Biden said. “His erratic policies and failure to uphold basic democratic principles have muddled our reputation and our place in the world.”

Biden has proposed two summits should he be elected — one on climate change and another on democracy — to position the U.S. as a leader in addressing global issues. Trump’s “America First” ideology, Biden said, has meant “America alone.”

Under Trump, the State Department has taken more of a backseat role than during past administrations. Hundreds of positions have been left vacant, and the Government Accountability Office released a study in March that raised concerns about overworked diplomats and gaps in security at embassies.

Biden and Warren have both proposed reinvesting in the State Department’s diplomatic corps. Warren has proposed doubling the size of the foreign service and creating new positions in underserved areas. She has also pledged to end the practice of giving diplomatic posts to wealthy donors, which would be a departure from both Trump and Obama. Instead, she’d fill the positions with career diplomats.

While Biden calls for a return to Obama-era foreign policy, Sanders and Warren have been staunch critics of military intervention in countries like Iraq, Afghanistan and Syria. Sanders recently led an effort in the Senate to end U.S. involvement in the civil war in Yemen, which the U.N. has called the world’s greatest humanitarian crisis.

On her website, Sen. Kamala Harris, D-Calif., has proposed ending “the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and protracted military engagements in places like Syria,” and has vowed to work on a “two-state solution” for Israel and the Palestinians. Harris, however, largely focuses her message on the stump on domestic issues such as criminal justice reform, curbing gun violence and taking on climate change.

Buttigieg, a veteran who served a tour in Afghanistan, has proposed similar ideas to those of other candidates, including ending the war in Afghanistan and rejoining the Paris Agreement. He would also recommit to the Iran nuclear deal and has proposed repealing the 2001 congressional authorization used to engage in foreign wars.

Biden was thrown a question at the first Democratic debate about his support for the Iraq War. He repeated his recurring defense that Bush abused the vote but quickly pivoted to his involvement in the 2011 troop withdrawal.

“I was responsible for getting 150,000 combat troops out of Iraq, and my son was one of them,” Biden said. “I also think we should not have combat troops in Afghanistan. It’s long overdue. It should end.”

Sanders seized the opportunity to point out that, unlike Biden, he had opposed the war from the beginning. Biden wasn’t given a chance to respond. Sanders’s dig didn’t receive much attention. Instead, Harris was able to steal the spotlight by focusing on Biden’s statements about segregationists and past opposition to federally mandated busing.

If other Democratic candidates attack Biden on his record with Iraq, his defense will likely be that he oversaw the withdrawal of troops. This response draws attention to the withdrawal, which critics have said caused a power vacuum that led to the rise of the Islamic State.

Trump has repeatedly shown that no attack is off limits for him. In 2016, he called Obama “the founder of ISIS,” referencing the troop withdrawal’s role in empowering the group. But it was Biden, not Obama, who oversaw the withdrawal. Biden’s ownership of the withdrawal only makes it easier for Trump to attack his record.

Read more from Yahoo News: