Bernie could win the Democratic nomination. But he has to show he can beat Trump.

Welcome to 2020 Vision, the Yahoo News column covering the presidential race with one key takeaway every weekday and a wrap-up each weekend. Reminder: There are 28 days until the Iowa caucuses and 302 days until the 2020 election.

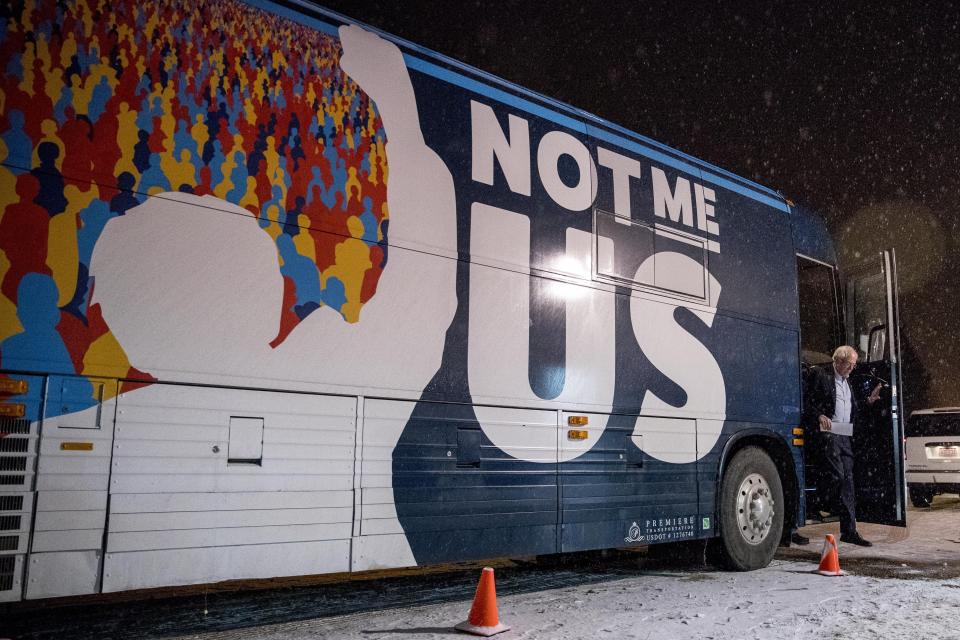

Long dismissed by pundits and underestimated by his rivals, Bernie Sanders spent his holiday season surging to the top of the polls in Iowa and New Hampshire, the first two states to vote in this year’s Democratic presidential primary. The only surveys released so far this month, both conducted by CBS News and YouGov, show the Vermont senator tied for first in the former and leading in the latter.

Nationally, Sanders trails only longtime polling leader Joe Biden, having just crossed the 20 percent threshold in the RealClear Politics average for the first time since last April, while both Elizabeth Warren and Pete Buttigieg have been trending downward.

And Sanders is far and away 2020’s top dog among Democrats when it comes to fundraising; his fourth-quarter haul of $34.5 million was the largest of the cycle, and no candidate ever has had as many individual donors — 5 million — by this point in the election cycle.

All of which has led some experts to a conclusion that would have been unthinkable a few months ago.

“Bernie is the frontrunner,” said former Barack Obama staffer Tommy Vietor on Monday’s episode of the influential progressive podcast “Pod Save America.” “He’s winning in Iowa and he’s winning in New Hampshire — I don’t know how to describe a frontrunner any other way. He raised $34.5 million this quarter without doing any fundraising events? It’s impossible to overstate how valuable that is to a candidate. If you have a strong performance in Iowa and you just get tens of millions of dollars rolling in online? I mean, he’s a juggernaut.”

Biden would, of course, debate Vietor’s frontrunner assessment. But what’s now clear is that Sanders’s path to the nomination is just as plausible as the former vice president’s: Finish strong in Iowa, win New Hampshire, win Nevada (a caucus state where his superior organization and solid Latino and union support could help); win the supreme prize of California on Super Tuesday (where Sanders has led in many recent polls); knock out Warren; consolidate the progressive vote; and compete with Biden for delegates all the way to the convention.

And so the question is no longer whether Sanders can win the Democratic nomination. Now he faces an even bigger question: Can he defeat Donald Trump?

It’s conventional wisdom that electability is the most important thing to Democratic voters; poll after poll has shown that picking a candidate who can evict Trump from the White House is the party’s top priority. And so every time a contender rises in the standings, he or she is subjected to an electability stress-test of sorts. Kamala Harris came first, and for whatever reason — race, gender, lack of message clarity — was found wanting. Elizabeth Warren was next; her awkward embrace of Medicare for All spooked Democrats who were otherwise ready to imagine her facing off against Trump, and she summarily fell from second place to fourth place in the polls.

Soon it will be Sanders’s turn.

His people have always known this was coming. They know the arguments. They know that their boss is a 78-year-old Jewish democratic socialist who has only ever won elections in Vermont, perhaps the bluest state in the nation. They know America has never elected a Jewish president, or a 78-year-old president, or a democratic socialist president. They know that Sanders’s signature “political revolution” — Medicare for All, Green New Deal, free college, zero student debt, a massive increase in education spending, comprehensive immigration reform and so on — would cost $51 trillion if enacted. They know that in a general election, Trump and his Republican allies would weaponize that sticker shock along with various episodes from Sanders’s past — his 10-day “honeymoon” in the Soviet Union; his Reagan-era sympathy for Marxist-inspired movements in the developing world; his wife’s troubled tenure as president of Burlington College — in ways that make whatever scrutiny Sanders has so far received from Democrats seem positively dainty in comparison.

And so they and other Bernie fans have for months pointed out that, in fact, their man has led Trump in nearly every national head-to-head poll conducted since the start of 2019, and that only Biden leads by more, on average. (Both Buttigieg and Warren have recently fallen behind the president.) They have highlighted a similar dynamic in key swing states such as Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, where recent polls have also showed Sanders, but not Warren, slightly ahead of Trump. They have noted that, in Vermont, Sanders, who identifies as an independent, always ran ahead of Democratic presidential campaigns — in part, says Vox’s Matthew Yglesias, “by getting the votes of some non-Republicans who backed Perot in the 1990s and, more recently, other third-party candidates such as Jill Stein, Ralph Nader, and Gary Johnson.” And they have argued that Sanders’s outsider, anti-establishment appeal would similarly expand the Democratic electorate in 2020, citing his strength among both working-class voters and younger nonvoters as evidence.

Sanders’s Democratic rivals have yet to weaponize the doubts about his electability. At next week’s debate in Des Moines, they may begin. To his committed supporters, none of their objections — that Bernie’s expensive plans would alienate the moderate suburbanites who fueled the Democratic House takeover in 2018; that recent polls in must-win Virginia have in fact showed Sanders trailing Trump by more than any of the other Democratic frontrunners — are likely to matter.

But he will be tested all the same.

The first test will be how he responds when challenged. Does he seem like the sort of candidate who is ready to deflect incoming fire from Republicans? This, more than anything policy-related, is the test that Warren failed when she stumbled over Medicare for All last fall, and it’s why Sanders, who also supports a single-payer system, hasn’t let it trip him up. Will he still project that same self-assurance while under attack from his Democratic rivals?

The second test will come later, starting with the results of the Iowa caucuses on Feb. 3. Right now, 36 percent of Sanders’s supporters in Iowa say they would be first-time caucus-goers, a higher percentage than Buttigieg’s 25 percent or Biden’s 24 percent. Will they show up on caucus night and propel Sanders to victory? If so, that will provide proof of his expand-the-electorate argument — and if he can continue to pull off the same trick in New Hampshire, Nevada, California and elsewhere, it will go a long way to quelling concerns about his electability.

It may even give him a chance to take the ultimate electability test next November.

Read more from Yahoo News:

Iran faces dilemma in avenging general's death: To strike back without starting a war

Did the U.S. 'assassinate' Iranian general or just kill him? Why it matters

Your Democratic primary cheat sheet: In the run-up to Iowa, who's still in the race?

PHOTOS: #MenToo: The hidden tragedy of male sexual abuse in the military