How Barack Obama's Love of Jazz Changed My Life

I never expected President Obama to teach me life lessons through music.

Maybe I shouldn’t have been surprised. After all, he brushed his shoulder off on the campaign trail, opened the doors of the White House to Common and Kendrick Lamar, enlisted a host of hip hop stars to help with policy initiatives, and appointed Janelle Monae, Jennifer Hudson, and Mary J. Blige as temporary diplomats onstage at State Dinners. Stevie Wonder, Usher, and Prince played his birthday parties until the sun came up, for crying out loud.

Even so, in our quieter moments, he dropped knowledge with a language foreign to me: jazz.

In 2013, the year Obama named me his chief speechwriter, he was slated to speak at the Lincoln Memorial fifty years to the day that Martin Luther King Jr., from the same spot, told the country about his dream. If there was ever a speech in which he was set up to fail, this was it.

Publicly, he expressed humility. “Well, first of all, let’s stipulate that my speech will not be as good,” he’d laugh. Behind closed doors, it was a different story. A week before the speech, I went to the Oval Office with Kyle O’Connor, a 27-year-old writer on my team, to see if we could shake any ideas loose from the president.

“Look,” Obama said, “the truth is, I don’t want to be doing this. I’d rather be hanging out with my girls, or playing golf, or drinking a martini.”

“And they say you’re not American,” I joked.

He let loose with a genuine laugh. But he could tell we were frustrated. It was our job to draft something he could play with. That’s how our collaboration with Obama worked—but for a speech as high-profile as this, we hoped that someone who famously described himself on the 2008 campaign as “a better speechwriter than my speechwriters” (almost always true, always an eye-rolling reminder) might at least offer us a starting point.

“Tell you what,” Obama said. “Read James Baldwin when you’re stuck. Listen to John Coltrane when you’re not.” Then he disappeared to take a phone call.

In the moment, his advice felt as useful as throwing a drowning man a sandwich. But I had to admit—it kind of worked. There was an effortless cool to Coltrane’s free jazz that lent me the sense that I knew what I was doing, a secret language coming from his saxophone that entered my ears and exited my fingers, that made me type faster, that fueled a sense of flow.

Baldwin was harder. His writing was something you had to commit to. But his moral clarity and righteous anger cut through bullshit like a laser through butter. Baldwin was an inspiration to write what was true.

Combined, Coltrane and Baldwin helped us churn out a draft that Obama, as he usually did, took to a higher place—weaving in a cut from Frederick Douglass, widening the circle of the speech by joining “the white steelworker, the immigrant dishwasher, and the Native American veteran” to the economic dreams of the Black custodian who marched fifty years earlier, surprising with some pointed criticism of the civil rights movement’s mistakes since then, and by adding, in his neat penmanship, something prescient and painful to read today, even though I still believe it: “We will have to be vigilant. We may suffer setbacks. But we will win these fights. This country has changed too much, and people of good will, regardless of party, are too plentiful, for those of ill will to change history’s currents.”

On the day of the speech, he adopted a preacher’s cadence for the homage to King’s peroration that he’d added to the ending the night before, promising that someday, if we kept at it, “those mountains will be made low, and those rough places will be made plain, and those crooked places, they’ll straighten out towards grace.”

That lesson, about Coltrane and Baldwin, changed the way I write. Another changed the way I live.

The State of the Union Address is a speech that every speechwriter dreams of writing until they get to do it: a Frankenstein’s Monster that requires stitching together forty or fifty or more different policy ideas into one coherent narrative. By January 2015, I’d ruined three consecutive Christmases trying to do just that. But for the first time, I felt I finally had a draft worth showing Obama eight days before the speech. A new record!

I included it in his evening briefing materials and expected to hear something the next morning. The morning came and went—nothing. Finally, a little after noon, his assistant Ferial Govashiri, an Iranian American from Orange County, barely thirty years old, called me in my windowless office tucked roughly under the Oval Office, and asked me to come upstairs.

When she made that request, it wasn’t so the president could give you a gold star, tell you how great you were, and send you on your way. As I tossed on my jacket and trudged upstairs, I worried that I’d have to rework a seven-thousand word speech.

The president wasn’t in the Oval Office. “He’s having lunch and wants you to join him,” Ferial said. That was unusual. I crossed the empty Oval, mentally preparing myself for an all-night rewrite, thinking through all the meetings I’d have to convene to come up with new policies.

I entered the small hallway of his private sanctum, passing his bathroom on the right and his study stuffed with family photos and a computer on the left, and poked my head into the small dining room at the end of the hall where Obama was sitting alone at the head of a six-seat table under a brass chandelier. Across the table from me, Muhammad Ali’s boxing gloves, signed for Obama, sat on a buffet table under The Peacemakers, a painting of Lincoln and his generals strategizing at the end of the Civil War.

“Hey,” he said, crunching on some baby carrots. “Sit down.”

Now I truly felt screwed.

“So,” he said, picking up his knife to cut a piece of chicken, “how you doing?”

“I’m fine, sir,” I replied, screaming internally, Oh my God, just tell me if the speech is okay!

“Look, I think the speech is in the best shape one of these has ever been a week out.” Everything in my body relaxed. “I actually think I could deliver this as is.” I tensed up again. When he said that, he never meant it. “But we have a week, so let’s make it even better.”

“Here’s the thing. Everything is in here,” he continued, tapping the draft State of the Union Address on the table with his right middle finger. “Every sentence says something. Every word means something. There’s no wasted space.” Raising his hand, palm down as if he were showing how tall you must be to ride this ride, he added, “The entire speech is up here at ten.” He pushed his hand down. “I need some of it down here, at six, seven, eight. You following me?”

“Yeah. I mean, that’s the thing about State of the Union Addresses—everything is in there.” My mind was already combing the text for topics I could excise and which cabinet agencies would complain the loudest about finding themselves on the cutting room floor.

Obama took a swig of unsweetened iced tea, sat forward, and placed his elbows on the table, hands clasped together, to make it clear that I was not following him. “Let me put it another way.” With his right index finger, he pointed at me. “You listen to Miles Davis?”

I wondered if this was a test to see if I’d followed Coltrane down the rabbit hole. But I fessed up and said no.

“You know what they say about Miles Davis?”

I did not.

“It’s the notes you don’t play,” he said, sitting back in his chair. “It’s the silences. That’s what made him so good. Silences can say more than noise can. I need a speech with some pauses, and some quiet moments, because they say something too. You feel me?”

By that point, I did. I knew exactly what he was talking about. I’d written plenty of speeches with those kinds of emotional moments, but the all-consuming nature of the State of the Union Address made me forget all that. What brief pride I’d felt in a speech that was in the best shape it had ever been a week ahead of time was quickly replaced by regret—regret that I’d been so consumed with making sure everything was in there that it made him complain that everything was in there.

“Good,” he finished, picking up his fork to dig into a chicken breast. “Like I said, we’re in great shape. I don’t want you to do any work tonight. I want you to go home, pour yourself a drink, and listen to some Miles Davis. And tomorrow, take another swing at it.”

He pointed his fork at me. “Find me some silences.”

I added them to the speech. But his directive stuck with me long after the speech was delivered. Finding the silences became more than a writing hack—it became a life hack.

Whenever I was writing a speech so stressful that I didn’t think I could meet the moment, I worked to find the silences not only in the text, but in the cacophony of my own life. Taking a walk with my wife. Going to the gym even though I hated it. Reading a story I’d had open in my browser tabs for weeks. Silly as it may sound, except to those who devoured The Bear this summer, a favorite stress reliever became perfecting my mise en place before cooking a meal.

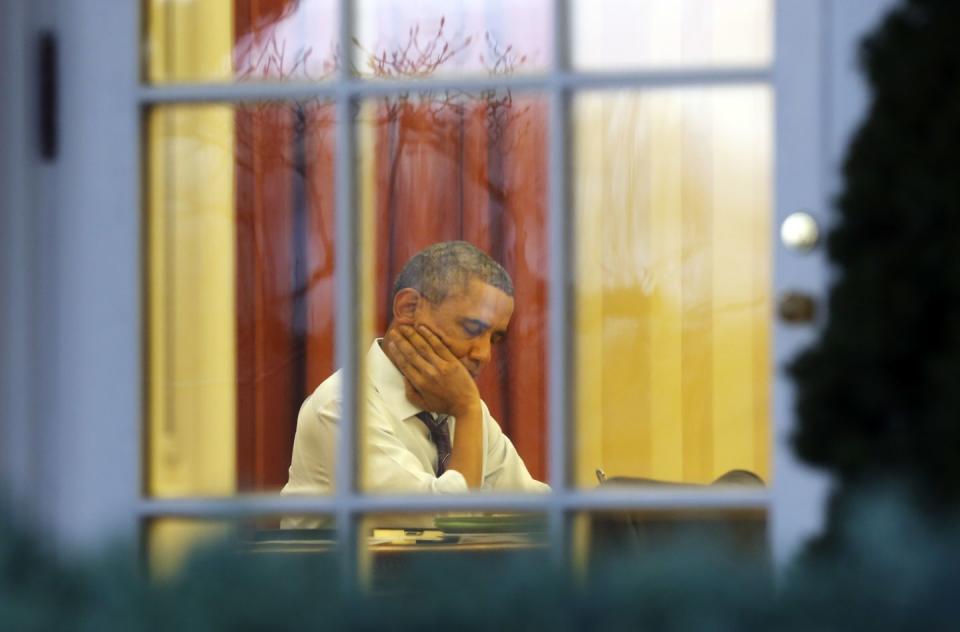

After eight years in the White House, when I suddenly had too many workstreams—continuing to work with President Obama, teaching speechwriting at Northwestern University, joining a high-end speechwriting firm, traveling to deliver speeches of my own, writing a book —and my indispensable calendar app suddenly had everything in it, with no wasted space, I started inserting blocks of time devoted to doing whatever I wanted to do. I started forcing the silences into my calendar. In his second term, President Obama had done the same, demanding of his schedulers an hour most days of “Desk Time.” He could read, write, pore through memos, whatever he wanted to do until his next meeting.

In 2020, my wife and I had our first child in pandemic-ravaged New York City—a daughter we named Grace—and I began to expand those blocks of time. It was hard at first, something that I had to commit myself to. You know phone addiction is real, for example, when you leave it in another room on purpose so that you can just be with your child and find yourself digging in your pocket anyway.

Finding the silences still requires effort. It’s still not a ritual, not ingrained in my habits; to announce the silences, my calendar and reminder apps still have to make some noise. But if there’s any alert I welcome, it’s the one that instructs me to whisk Gracie to the playground at the golden hour, maybe with Coltrane playing “My Favorite Things” from the back of the stroller—the only activity I know that seems to bend time until, impossibly, it expands.

You Might Also Like