Amid homelessness, Asheville couple marries in church where they took shelter years before

ASHEVILLE - Christie Glenn, the bride, wore gauzy, costume-store wings down the aisle, a white leather jacket over a floor-length dress. The wedding was held in the church’s sanctuary, but a broken boiler meant the room was frigid, and the few attendees were bundled in coats and hats.

At the altar rail, officiant Melanie Robertson coached Christie through a few deep breaths. Robertson first met Christie and groom, Jeffery Glenn, two winters earlier in the basement of that same church. It had opened as an emergency shelter when other options floundered.

Robertson called the ceremony “full circle.”

In the moments before rings were exchanged, Christie leaned forward to press her face against Jeffery’s chest.

“I’m the one who’s been running,” Christie would tell the Citizen Times after the Jan. 21 ceremony. But not anymore.

The couple had a hotel room booked for the honeymoon at the Red Roof Inn in West Asheville. But after that night, they would go back to camping on the river. It’s what they have done for the last four years, Christie said, off and on, during their time spent homeless in Asheville.

‘A new family’

Christie, 41, and Jeffery, 52, found their way to Trinity United Methodist Church in winter 2021. The church opened its Fellowship Hall as a Code Purple emergency shelter, which triggers when temperatures drop below freezing, after several Code Purple nights were called with no shelter options available.

The goal, Robertson said in January 2022, was to fill in the gaps. Unlike other shelters, most separated by gender, Trinity would provide beds for couples. They also allowed pets and were openly inclusive of LGBTQ+ people.

Back in 2022, Christie called those organizing the shelter, including Robertson and Amanda Kollar who would later be in her bridal party, “angels in our life. A new family.”

Shelters are a constant challenge for Christie and Jeffery. They don’t like to be separated. It’s bad for Jeffery’s mental health, he said. Sometimes he gets seizures. They often camp in the River Arts District along the French Broad River. For a wedding gift, they asked for a new tent.

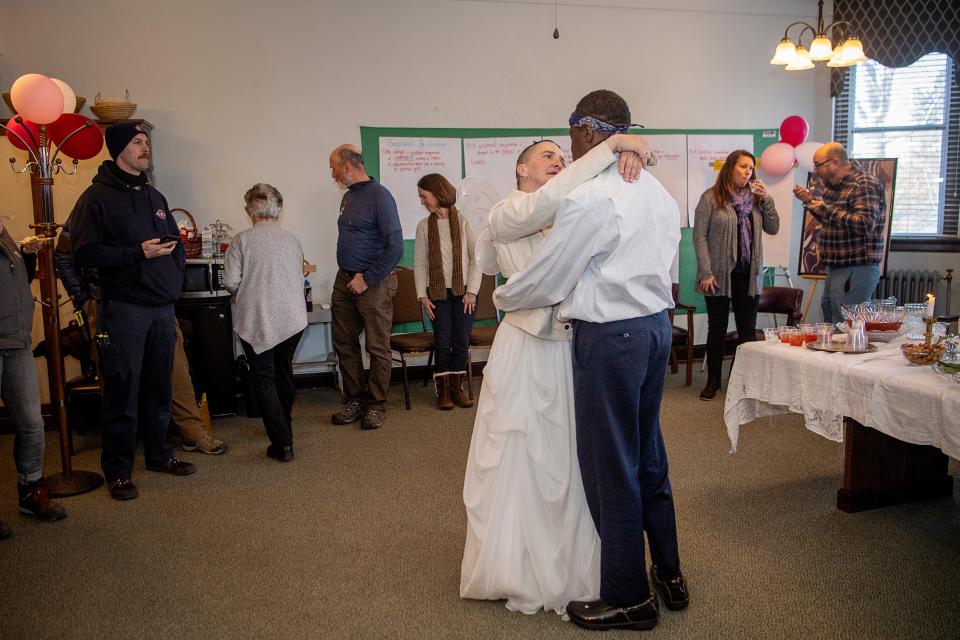

The reception was held across the hall from the sanctuary. Cake cutting proceeded in typical fashion — mugging for photos from their seats and showing off their wedding bands, Jeffery dutifully wiping icing off Christie’s face.

“They have been incredibly devoted to each other,” Robertson said, observing. “They have stuck together through thick and thin.”

The room was full of people from the original Trinity Code Purple effort — like Robertson and Kollar, who went on to open the Jubilee Alternative Micro-Shelter downtown. The Jubilee shelter effort then transformed into a new nonprofit, Wildflower House, providing permanent housing for people exiting homelessness, a step beyond transitional housing.

Members of Buncombe County’s Community Paramedicine program, led by Claire Hubbard, who supported the Code Purple effort from “the ground up,” and other volunteers also attended.

Trinity became part of Winter Safe Shelter, a partnership between three area churches and Counterflow LLC, which is now operating a 20-bed nighttime shelter in Homeward Bound’s AHOPE Day Center.

Robertson said that first winter providing Code Purple shelter, scrambling to create a program in a matter of days, ignited a desire to continue the work.

“We saw the gaps,” she said.

Hubbard has known both Christie and Jeffery for years. She said, in the beginning, she never imagined she’d get to stand at the reception of their wedding, watching them eat cake and slow dance. Like Robertson, the first words that came to her were, “full circle.”

“How do I feel seeing this? We measure success in so many ways that don’t honor this kind of thing,” she said. “We measure outcomes and success constantly, but this is a pretty big one that there is no way to record, to put into data, but it’s amazing to see two people come so far.”

Longtime love story

Jeffery said he and Christie met in Charlotte. He was born there, according to their wedding certificate. Christie grew up in Atlanta. By their count, they’ve been together for eight years.

“It’s always been Christie and Jeffery ever since I’ve known them,” said Frank Yaun, Kollar’s partner. He walked Christie down the aisle. Kollar’s 13-year-old son, Harrison, was the best man.

Laurel Stiles, a volunteer at ABCCM’s Transformation Village, which offers Code Purple shelter for women, said she works the 7:45 p.m.–midnight shift, and met Christie there.

“If she is not talking to him, she’s talking about him,” Stiles said of Christie. “I instantly fell in love with their story.”

Robertson emphasized how difficult it is to find stability while unhoused. To get a job. To keep it. To hold on to possessions and community when encampments are always under threat of being cleared.

“The beauty of this story is that they are finding a sense of stability in each other, and in a community that they’ve built over the years with the folks that were here,” she said, “standing and witnessing this beautiful part of life within the context of the difficulty.”

Lack of housing and other hurdles

A few days before their late January wedding, Kollar took Jeffery and Christie to Walmart to buy rings. They got a giftcard to Cracker Barrel for dinner after the ceremony.

Kollar said she isn’t sure if married life will look any differently for Christie and Jeffery, but that “this is how they live. They have more joy on a regular basis than I probably do.”

Christie said they’ve been on the city public housing lists, which are often thousands of names long and can mean months-long waits.

But as Robertson added, housing is a “fickle” thing. Even once you get it, it can be easy to lose.

Asheville’s rents are among the highest in the state and jumped 36% in less than two years. Amid an affordable housing crisis, mirroring nationwide trends, the city’s homelessness numbers rose dramatically at the onset of the pandemic.

The latest point in time count numbers from a January 2023 found 573 people experiencing homelessness in Asheville, 171 of which are unsheltered. Overall, homelessness was down 10% from the previous year, but remained higher than pre-pandemic levels.

There’s a need for more shelters, advocates say. Shelters in the city often find themselves at capacity and for many people experiencing homelessness there are barriers to entry — like required ID, sobriety, or having a partner or pets — that will stop them before they even get in the door.

Camping is illegal in the city of Asheville. But many people say it’s their only choice.

Christie wishes more people would put themselves in their shoes.

“They would realize how it is out here,” she said. “If they had a partner like I do, they would realize how hard it is to be separated from that person. And how it is to find food, shelter. Plus, some people who have felonies, like me and him, it’s hard for us to get a job.”

Jeffery was convicted of a felony in the 1990s, according to records from the North Carolina Department of Adult Correction. Mecklenburg County court records show that Christie has been in and out of jail there for misdemeanors for the last decade.

What is it like to experience homelessness in Asheville?

It was gray and drizzling, but tepidly warm, four days later when Jeffery and Christie were back in the pews — this time at Haywood Street Congregation on the cusp of downtown.

Late morning, people were stretched out asleep in the sanctuary and in the well of the front vestibule. In an atrium-like room on the first floor, Christie was tangling with CareSource, an insurer that provides Medicaid services, trying to activate a plastic rewards card through the labyrinthine snarl of an automated customer service line.

She spent the morning largely on hold. First, with customer service. Then upon finding the card was empty, desperation mounting, on a similar spiral with Allegiant airlines, trying to suss out ticket prices.

They’re leaving Asheville, Christie said, this time for good.

“Asheville ain’t got nothing for us really,” she said.

She’s tired of separating from Jeffery to sleep in Code Purple shelter. Tired of the “drugs and idiots.” Tired of people tearing up their tents or stealing from them.

“Being on these streets. We’re tired of being broke.”

They got a job at a traveling carnival, where they worked in 2022, running rides and traveling up and down the East Coast. All they needed was to secure two tickets to Tampa, Florida.

When asked what they’ll miss, it’s not the city, they say, but the people: Haywood Street Congregation, Trinity church, Robertson and Kollar, the community paramedics.

‘The married life’

Christie and Jeffery said they spent the morning of Jan. 25 at the Buncombe County Courthouse, trying to get a copy of their marriage license. Upon learning there was a $10 fee, they turned back. The next few hours were spent trying to find the money, while also placing calls for plane tickets.

They wanted to leave as soon as possible.

In the meantime, it was nearly noon. Jeffery stayed behind at Haywood Street and Christie set off for Western Carolina Rescue Ministries a few blocks away, which serves Styrofoam boxes of food most days from its driveway.

“I’m loving the married life,” Christie said. She and Jeffery exchanged ‘I love you’s’ before she walked out the door.

She had an easy rapport with the people she passed. A young man who just came to town, living in his car with his dog. Another man in boots and a hardhat, sitting on the curb, who has been working a temp construction job across the street. Someone she exchanged a few words and a cigarette with at the corner.

People congregated at the chain-link fence that bridges the drive, waiting for the gate to open. Christie paced in wide circles, her quilted hat wet with rain, in an oversize sweatshirt that might be Jeffrey’s. She was back on hold with CareSource.

She returned to Haywood Street with two hot lunches in hand. White bread, beans, salad, chicken. A brief exchange with a Haywood Street staff member, asking about the $200 needed for tickets, left both looking tense. Christie started googling the number for Red Door Ministry, hopeful they would have a solution. But it felt like options were drying up.

In Tampa

A week later, Jeffery called from Tampa. On speaker phone, Christie said they made it there the day before — $185 in plane tickets covered by the community paramedics and Wildflower House.

Jeffery’s mom lives in Florida. But they haven’t seen her yet.

They were waiting for a ride to work at the “winter quarters,” a spot for storing rides, annual maintenance and a gathering point for carnival workers.

She’s hopeful about the future.

It was their second time flying. Jeffery was a little scared, Christie said. After a murmur from Jeffery in the background, she added, “at first.”

“But after that, we were looking out the window together.”

More: Asheville, Buncombe annual homeless count draws record number of volunteers

More: 'Rising rates' of homelessness? Chuck Edwards hosts summit in Asheville

Sarah Honosky is the city government reporter for the Asheville Citizen Times, part of the USA TODAY Network. News Tips? Email [email protected] or message on Twitter at @slhonosky. Please support local, daily journalism with a subscription to the Citizen Times.

This article originally appeared on Asheville Citizen Times: Asheville newlywed couple brave homelessness life on streets