80 years of Townes Van Zandt: Meet the music giant Fort Worth barely knows

The well-worn grave marker in a remote cemetery near Eagle Mountain Lake draws thousands of visitors. They leave liquor, or cigarettes, or charcoal or crayons from gravestone rubbings.

“To Live’s To Fly,” the epitaph reads: “John Townes Van Zandt / March 7, 1944 / January 1, 1997.”

Eighty years after one of country music’s greatest songwriters was born into west side wealth in a Texas pioneer family, Van Zandt has now been gone for a generation.

Yet his songs like “Pancho & Lefty” live on in movies and streaming shows, and authors and filmmakers seem more fascinated than ever with a singer-songwriter who lived as a child on Washington Terrace in Rivercrest, yet remained mostly unknown in his home town.

“I think he should have a statue like Stevie Ray Vaughan has [in Austin],” said Fort Worth musician Bruce Payne, host and sponsor of the annual HomeTOWNESfest tribute.

This year’s event is March 9-10 in the Southside Preservation Hall and Rose Chapel, 1519 Lipscomb St.

Drummer Jack “Bullett” Harris of Fort Worth knew Van Zandt when Harris was the drummer for country’s Steve Earle.

“Townes is exactly like Ornette Coleman,” Harris said, naming the famous contemporary jazz saxophonist. “They were never given enough attention in Fort Worth.”

Fort Worth’s list of singing stars is long. Kelly Clarkson started elementary school here before moving to Burleson. Leon Bridges tours the world with a backdrop reading, “Fort Worth.”

John Denver and Broadway star Betty Buckley are close to Van Zandt’s generation, and both went to Arlington Heights High School with some of his old grade-school playmates. Songwriter T Bone Burnett and gospel’s Kirk Franklin are from Fort Worth.

That’s not to mention Willie Nelson, who grew up 70 miles south but lived here in two stints, singing, hosting radio shows, writing songs and, in 1954, smoking his first marijuana.

But Austin, the “Live Music Capital of the World,” does not have a Hotel Clarkson or a Hotel Denver.

It has a Hotel Van Zandt, with a music club named for his dog, Geraldine.

“He was never promoted, and his records were on these dinky little labels, but to this day there is a fascination with Townes’ songs,” said John Lomax III of Nashville, an author, folklorist and former Van Zandt manager. He will speak at the March 9 event.

“Many other musicians have passed away who had far more success in their careers but no posthumous success,” Lomax said. But Van Zandt’s songs are still selling.

Van Zandt lived in Fort Worth until age 9. He went to Arlington Heights Elementary School, now Boulevard Heights School.

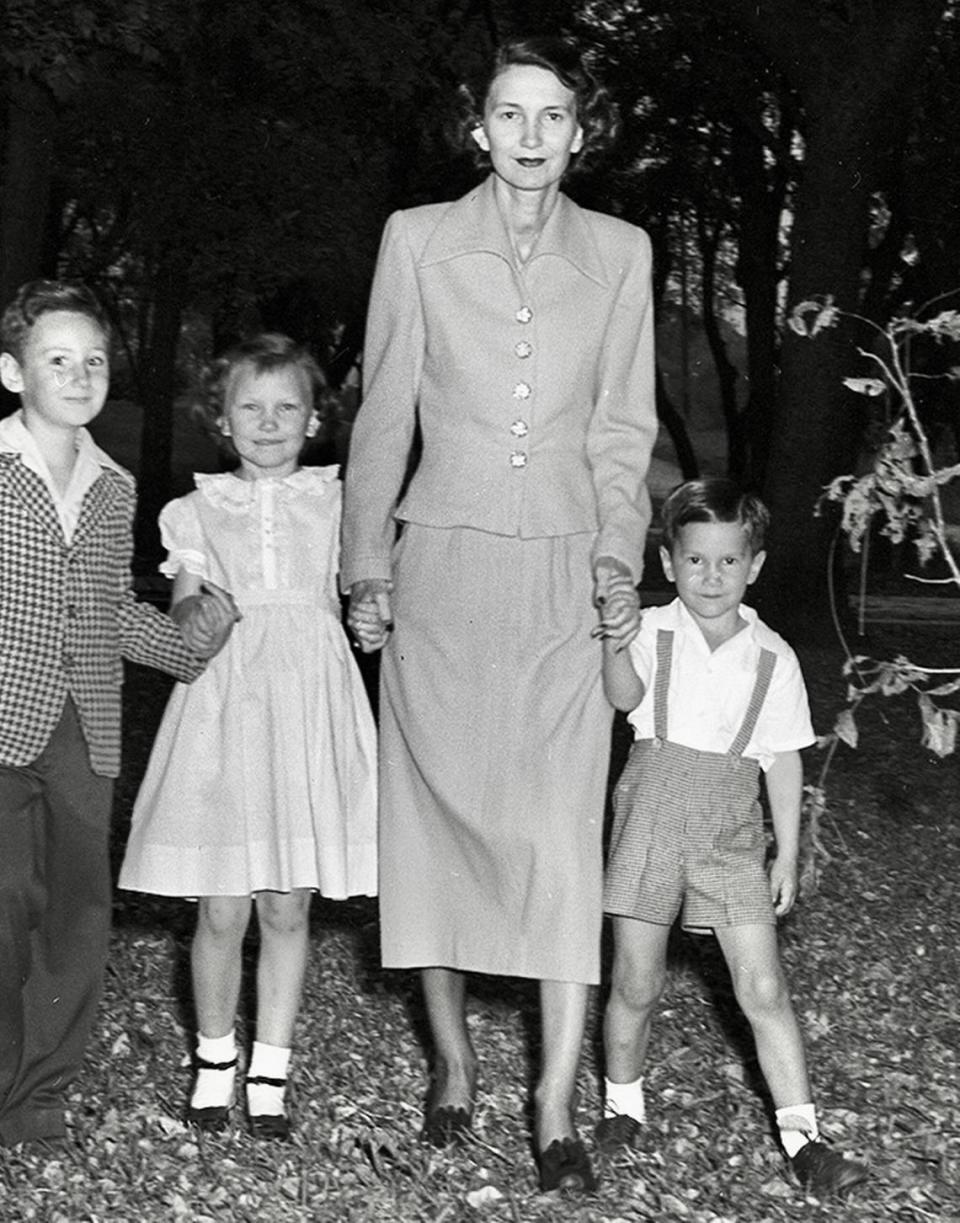

His parents were both from high-powered law families, Dorothy Townes Van Zandt from Houston and Harris Van Zandt as a lawyer for Pure Oil.

But the family history goes back to the Republic of Texas. Townes Van Zandt’s great-great-grandfather, Isaac Van Zandt, was the Republic’s ambassador to the U.S. There’s a county named for him.

A great-great-uncle was “Major” K.M. Van Zandt, leader of a Texas infantry unit in the Civil War and later a pioneer Fort Worth banker and school official. One of Townes’ cousins is TV and movies actor Ned Van Zandt, and a distant cousin was late actor and TV superhero Van Williams of Fort Worth.

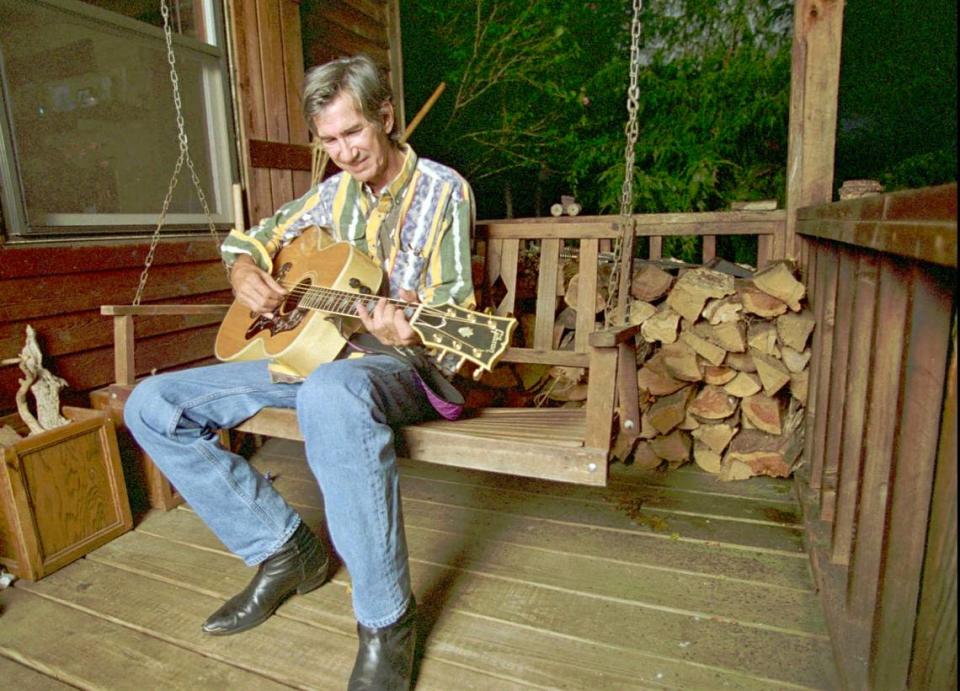

The Star-Telegram photo archive at UT Arlington includes three photos of him as a little boy, two with his mother and one raising money for a newspaper charity.

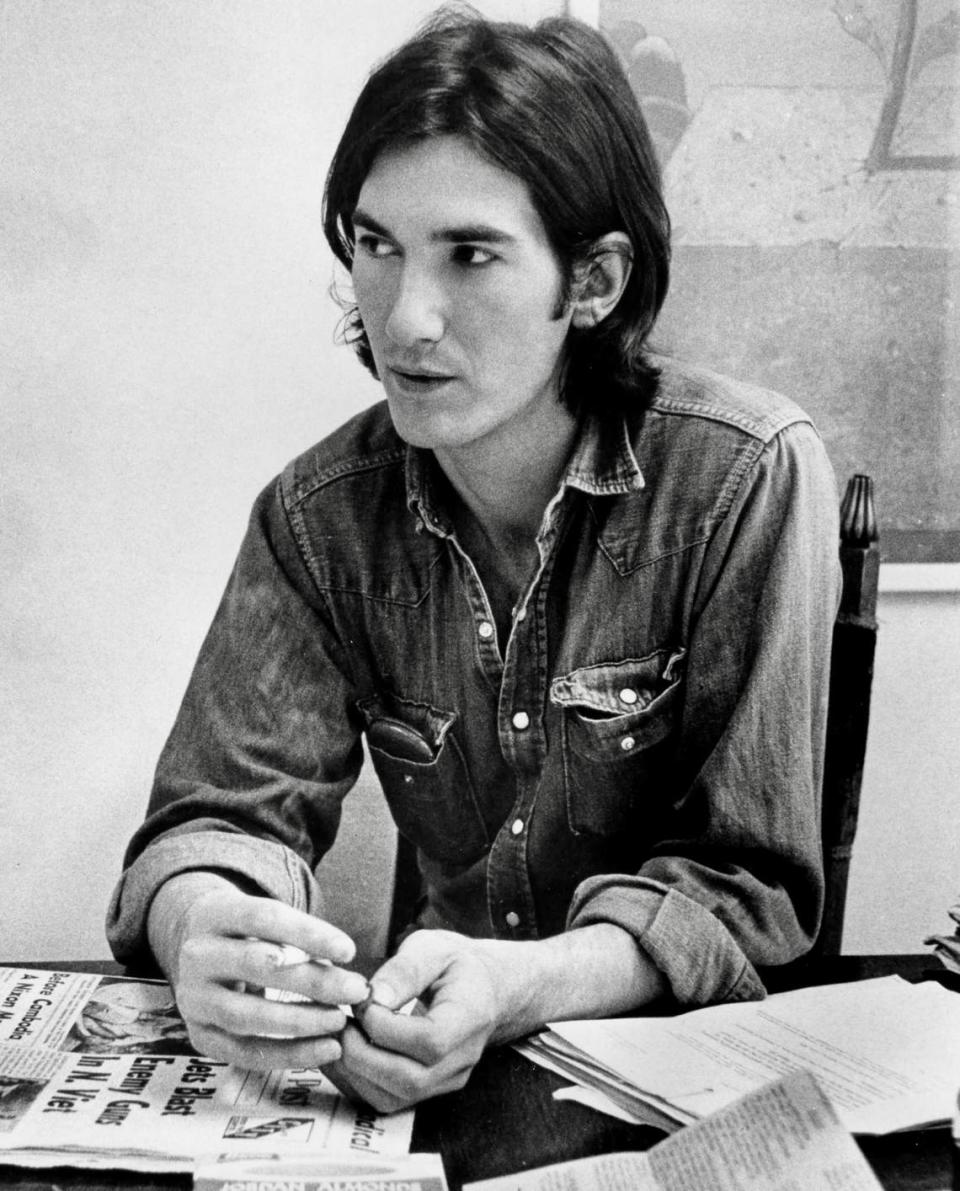

In a June 1972 Star-Telegram interview for his album, jokingly named “The Late Great Townes Van Zandt,” Van Zandt deadpanned that the only thing he remembered about Fort Worth was “I ran away from home a lot.”

But he always talked about Fort Worth, Harris said. When he saw the city limit sign, he joked, “Fort Worth — bigger than Dallas.”

“His work had been in Austin and Nashville, and that’s what people knew until Steve Earle wrote ‘Fort Worth Blues’ ” as a tribute, Payne said.

“Everybody knows he’s a Fort Worth guy and member of a founding family.”

I can think of only one other local grave that might be visited as often as Van Zandt’s, on land donated by his ancestors for the tiny Dido Cemetery, 12341 Morris-Dido-Newark Road.

But I don’t really think more people visit Lee Harvey Oswald.

Van Zandt’s obituaries in 1977 dwelled on his dark side.

He is seen as a troubled troubadour, self-deprecating but also self-destructive. He was a childhood genius who suffered from mental illness, as depicted in the 2004 biopic “Be Here to Love Me.”

Lomax said he is coming to Fort Worth March 9 in part to counter that image.

“Townes wasn’t this tragic figure sitting in a darkroom full of gloom and doom,” Lomax said.

“He had a wicked sense of humor.”

Once, Van Zandt pranked Lomax into thinking he was the first performer to sing with his eyes closed.

Later that day, Lomax was around Billy Gibbons of ZZ Top, a band that played early dates at the old Cellar nightclub in Fort Worth.

“I breathlessly informed Billy Gibbons that Townes invented singing with your eyes closed,” Lomax said.

“He looked at me as if I had a coyote on my head.”

Harris, Earle’s drummer, said what he remembers about Van Zandt is that “he was very humble.”

“He was not all that sold on himself,” Harris said.

The first HomeTOWNESfest events 10 years ago drew sellout crowds at a smaller venue, but attendance has varied. This year’s event features Lomax at 8 p.m. March 9 and local musicians doing Van Zandt’s songs at 2 p.m. March 10.

Payne said this year’s event is a fundraiser to maintain and improve the Southside Preservation Hall and Rose Chapel, 1519 Lipscomb St., one of the city’s endangered live music venues.

“It’s a thrill to have John [Lomax] here,” Payne said. “We get to hear from people who knew Townes and musicians who knew Townes.”

He wants Fort Worth to know Townes.