2023 was the deadliest year for killings by police in the US. Experts say this is why

The U.S. set another grim record last year as the number of people killed by police continued its steady increase, according to a new report released Wednesday by Mapping Police Violence.

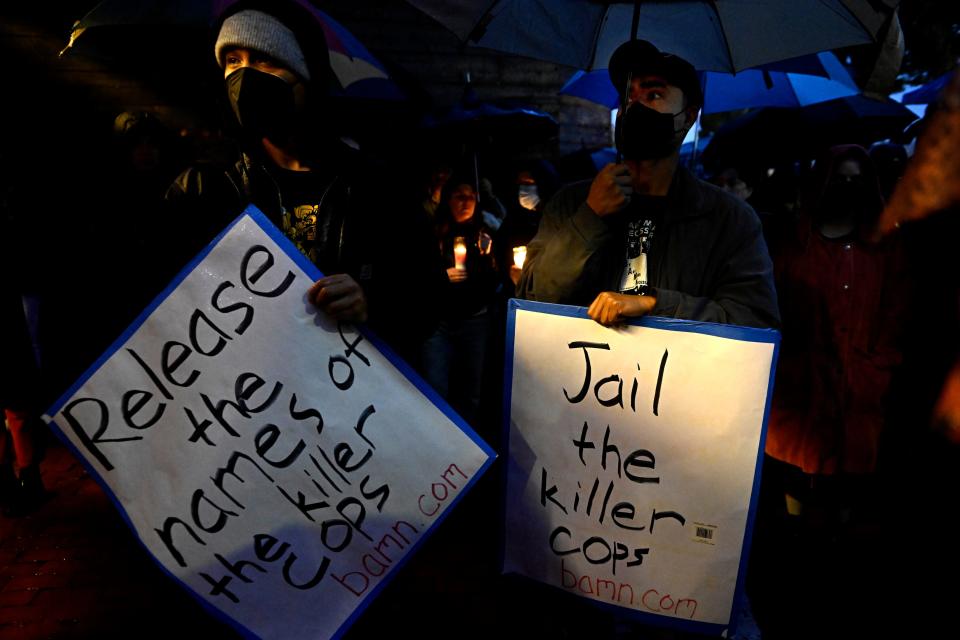

Police killed more than 1,300 people in 2023, a year that saw several high-profile cases including the fatal beating of Tyre Nichols in Memphis, Tennessee, the shooting of an environmental activist who was protesting the construction of a police and fire training center near Atlanta and the death of a Virginia man who was "smothered" in a hospital. There were only 14 days without a police killing last year and on average, law enforcement officers killed someone every 6.6 hours, according to the report, which is primarily based on news reports and includes data from state and local government agencies.

The number of such killings has risen since Campaign Zero, which runs the Mapping Police Violence project, began tracking the data in 2013. Meanwhile last year, the number of people killed by gunfire and of officers killed in the line of duty declined, according to data from the Gun Violence Archive. There was an increase in the number of police officers shot.

"We've seen it stay similar or even creep up a little bit at times when crime was falling or at times when crime was increasing. We saw it persist throughout a global pandemic when people were staying home for several weeks, months," said Justin Nix, a criminal justice professor at the University of Nebraska Omaha. "It appears to me then that the only way to get this number down significantly would be to make more significant changes to, you know, what policing means in this country."

How many people were killed by police in 2023?

At least 1,329 people were killed by police last year, an increase from 1,250 the year prior, according to Mapping Police Violence. New Mexico, where a man was fatally shot by police officers who responded to the wrong address in April, had the highest rate of fatalities per capita, with 10.9 killings per 1 million residents, followed by Alaska and West Virginia.

Nearly 90% of those killed were shot, according to Abdul Nasser Rad, managing director of research and data at Campaign Zero. Rad said public records indicate at least 42% of the incidents were captured on body-worn cameras, though the footage may not be publicly accessible. Body camera video can sometimes contradict initial police accounts of an incident – if departments release it.

Cops stand trial in high-profile cases Is it easier to prosecute police now?

Victims include people of color, people with mental health problems

Rad said racial disparities seen in previous years have also persisted at a similar rate. Black people, for example, were nearly three times were more likely than white people to be killed by police. Rad noted race is one of the hardest variables to track and the race of the person killed was unknown in more than 20% of the encounters.

In roughly 25% of the encounters, the victim was showing signs of a mental health problem or alcohol or drug use, but these factors are not always reported or clear, Rad said. In one such case, three San Antonio Police officers were charged with murder in June after a woman experiencing a mental health crisis in her apartment was shot.

What's causing the increase in police killings?

Nix said that the same factors that he believes drove the increase in the number of police officers shot last year is likely contributing to the consistent increase in police shootings of civilians: guns.

"When you ask human beings to go out and police a country awash with guns and train them and socialize them in their heads that a gun could be lurking around any corner, this is what you get," Nix said.

He said the numbers indicate that piecemeal, patchwork reforms made over the last decade including the increase in body cameras and de-escalation and bias awareness trainings, haven't had much impact and more significant changes needed to be made.

However Chuck Wexler, executive director of the Police Executive Research Forum, said research shows de-escalation training provided by his organization can work. Wexler said the problem is that not all of the country's more than 18,000 law enforcement agencies have actually implemented such training, efforts he said are complicated by staffing issues and pushback from departments that believe the training they have is sufficient.

"They're working off of outdated, antiquated training," he said. "And until that training changes, and until the culture with it changes, that number is going to be way too high. We can cut officer involved shootings with the right training."

2024 gun law rankings: These new gun laws change the rules of firearm ownership in America. Here's how

Better data needed, researchers say

Rad said tracking these incidents can still be grueling, disheartening and frustrating and better data is needed to capture the full scope of the problem. More than half of U.S. police killings are not reported in official government data, according to a 2021 peer-reviewed study in The Lancet.

As a result, researchers like Rad have to rely on news reports, which can lack critical information. He said training for local journalists "would be so critical to improving the data quality."

Nix agreed better data is needed, including more data on nonfatal police shootings. According to the Gun Violence Archive more than 800 people were shot and injured by police in 2023.

"We're still trying to put a puzzle together where we don't have all the pieces and that's hard to do," he said. "We can't manage the problem if we don't know the extent of it."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Police officers killed a record number of people in 2023. Here's why