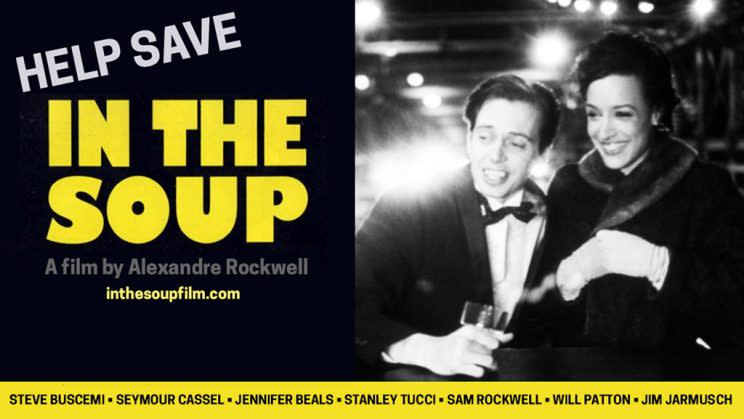

‘In the Soup’ Exclusive: Kickstarter Campaign Launches to Help Restore Class of ’92 Sundance Winner

The Reservoir Dogs had their day at the 1992 Sundance Film Festival, where Quentin Tarantino’s bloody crime drama launched the former video store clerk on his quarter-century reign as indie movie royalty. But if Reservoir Dogs dominated the conversation in Park City, it didn’t dominate the festival’s awards ceremony. Instead, the big winner of that epochal year proved to be In the Soup, a black-and-white comedy co-written and directed by Alexandre Rockwell, and featuring such stars-in-the-making as Steve Buscemi, Sam Rockwell, and Stanley Tucci, as well as established actors like Jennifer Beals, Carol Kane, and Seymour Cassel.

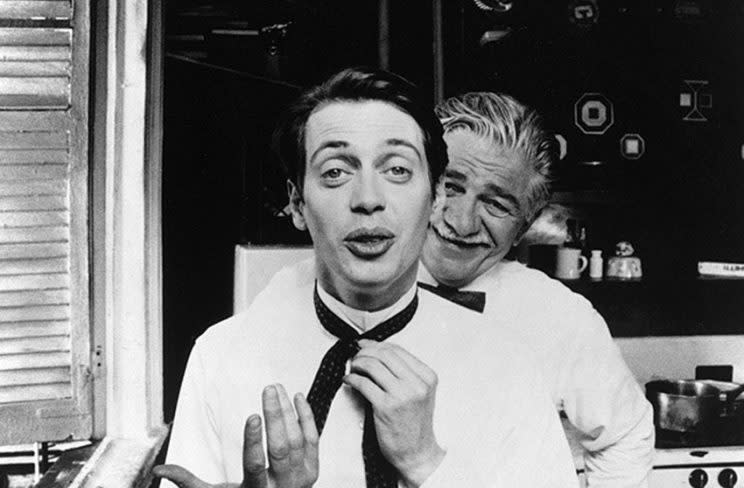

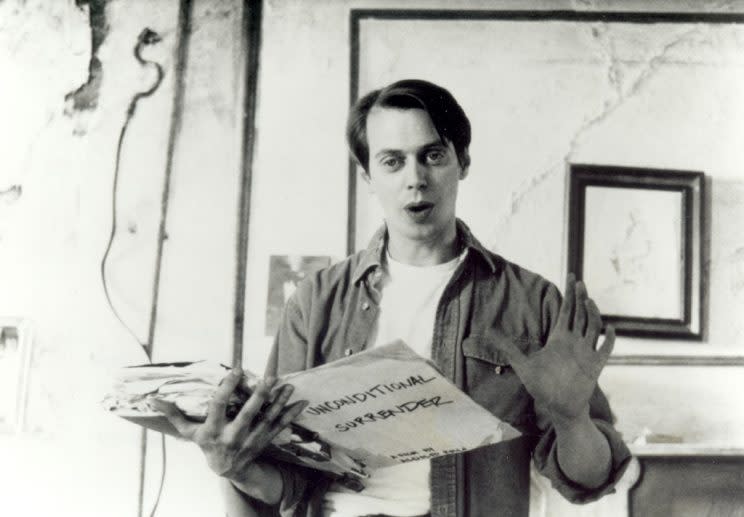

Sundance audiences, not to mention the jury, embraced the scruffy roman a clef tale of a struggling filmmaker, Aldolpho Rollo (Buscemi), who is willing to do anything to get his dream project financed, up to and including befriending a career criminal (Cassel). In the Soup picked up the Grand Jury Prize, as well as a Special Jury Prize for Acting, leading those associated with the film to dream of a lucrative distribution deal followed by a successful theatrical run. “This was when the Sundance feeding frenzy had just started,” Rockwell tells Yahoo Movies. “Jim Stark, the producer of the film, felt he had something really golden.”

Unfortunately, that golden luster faded as Sundance retreated into the past, and the film languished without a deal, the result, Rockwell says, of his producer’s decision to not more aggressively pursue a distributor at the festival. Eventually, the now-defunct label Triton Pictures acquired the movie, but lacked the funds to promote it effectively. Released in October, nine months after its festival premiere, In the Soup grossed a little over $250,000, well below the nearly $3 million earned by Reservoir Dogs. That fate has since been repeated by any number of buzzy Sundance titles that failed to make a dent in the mainstream marketplace. “There used to be a term that was so nauseating for me to hear,” Rockwell remarks with a rueful laugh. “It was ‘You got ‘Souped.'”

Flash forward 25 years, and a new generation of film lovers have the chance to be part of bringing In the Soup out of semi-obscurity. The upstart distributor, Factory 25, is launching a Kickstarter campaign aimed at restoring Rockwell’s 1992 film. Overseen by Factory 25 founder Matt Grady, the campaign is seeking to raise at least $54,000 — funds that will go toward patching up the director’s own print of the film, which was severely damaged following a rare public screening at the Tarantino-owned New Beverly Cinema.

“I had this one archival print that was printed on very rare film stock that Kodak doesn’t make anymore,” Rockwell explains. “We tracked down an interpositive print that doesn’t have the soundtrack, but it was made on the same stock I had. We’re going to go back and splice it into the damaged areas, and then you can transfer that and digitize it at a very high level so that everything from streaming to Blu-ray can be the same quality as that print. It’s going to be very close to what the original looks like.”

Once restored, the plan is to use additional funds to rerelease In the Soup for special theatrical engagements, as well as Blu-ray and streaming services. This new version would supplant a DVD previously released by Fantoma Films in 2004. “It wasn’t very well-transferred,” Rockwell says of that earlier release. It didn’t help that, much like Triton Pictures, Fantoma closed its doors not long after In the Soup’s release. “It’s not a film that drives people out of business, but somehow it gets unlucky.”

Backers of the Kickstarter, which runs from July 31 through August 30, will be able to choose from a variety of potential rewards depending on their contribution level. Rockwell has donated several mementos from the production, among them continuity photos and slides taken at Sundance in 1992, while Buscemi, Beals, and Tucci will be signing film stills and recording voicemails. Other rewards include a New York lunch date with Buscemi and Rockwell, as well as private sessions with industry professionals covering the ins-and-outs of casting, editing, and script supervision. Visit the film’s official Kickstarter page to kick in some funds, and read on for more of our chat with Rockwell about what it was like to be part of Sundance’s famed Class of ’92 and capturing a long-vanished version of New York City.

I was a high school movie buff during the 1992 Sundance Film Festival, and I remember reading about Reservoir Dogs and all of the other great films that emerged out of that year’s lineup. What was it like being there on the ground?

It was weird, because we all went in very na?ve; we were all newbies. It was very low-key at that time, and more of a filmmaker-y festival. Quentin and I kept a distance from each other at first. He already had an agent, and the buzz was in his ear, because people in the industry really responded to Reservoir Dogs. Whereas In the Soup was more of an audience-pleaser. I had no idea I was going to win anything; I was so na?ve that when my publicist told me to sit in the front row, I thought, “That’s a great seat!” [When the film won] it was so intense that I broke into tears. At the party afterwards, Quentin came up to me, threw his arms around me and said, “Congratulations, man.” He was such a geeky shaggy dog in those days. He’d had all this pressure on him to think he might win something, so I think a lot of people around him were pissed, but he wasn’t. We became really good friends after that. He came and lived with me in New York for a little while.

Reservoir Dogs and In the Soup almost occupy opposite extremes of the indie film spectrum: one is an L.A. crime drama with mainstream aspirations and the other is a scrappy New York black-and-white comedy.

It’s like the time that Charlie Chaplin and Jean Cocteau met on an ocean liner. Cocteau said, “You are the poet of the sunshine, and I am the poet of the night.” Quentin and I had very different worldviews, but we came from a similar place in that we were both about character-driven work. It’s also interesting that Steve is in both of our movies. He shot In the Soup first, and when he came back from doing Reservoir Dogs, I remember him telling me about this guy Quentin. He was so excited about him and what a character he was. So Steve was the guy who brought us together.

In the Soup shares some of the same sensibility of early ’80s New York indie cinema. Jim Jarmusch even has a role in your film. Did you intend it to be a throwback to those earlier movies?

It’s a throwback to a certain time in the live of a young artist when it’s all about the passion, the fun and excitement of the thing itself. It captures that time of life when you’re not worried so much about your career or money. I didn’t go to NYU like Jim did; my college was the Lower East Side of New York. I was bussing tables and running around making films. I didn’t even think about distribution! New York was very different then; you just needed enough money to get ramen noodle soup. My rent was $75 a month. I could work in a restaurant one night a week, do a couple of other odd jobs and maybe have my mother send me $50 and I could make rent and go out and have a good time.

The version of New York that exists in In the Soup is long gone now. Were you aware that era was passing as you made the film?

It is almost like an ethnographic film almost of that time in New York. I’m not sure was aware that it was passing. I just know that it was alive! Everything was exciting; the Lower East Side was almost like a studio backlot. You’d walk down St. Mark’s Place and bump into Steve coming out of St. Mark’s Church. Sam Rockwell was in an acting class with me. Stanley Tucci was doing plays and stuff. You could got into any store and meet a great actor who would come and work on a film for nothing. It captures that time in a bottle.

So let’s jump ahead to after Sundance: What happens after the film gets released and how does it end up at the New Beverly in tatters?

There’s a journey there. Triton took the film and wanted to release it, but they went out of business, so they had no money to promote it or anything. In those days, there was a lot of push for color [films] amongst video companies. I refused to have it come out in color, but I did do a kind of sepia version, and they rejected it. So that didn’t help in terms of its secondary life. Then it just disappeared. It would show every once in awhile, and it got this reputation as the movie that won Sundance in 1992 that no one had seen. That was fun to hear for awhile, but not so fun when you realized it would have done really well!

Quentin asked to show my print at the New Beverly a few years ago. I wasn’t there, so I don’t know what happened, but two reels got torn up and shredded in the projector. They were mortified, and said they would get it fixed, but it was prohibitively expensive. Had I known I could never make that print again, I would never have shown it. I should have treated it like a one-of-a-kind rarity. But in a way, it’s kind of great because it opened up this whole Kickstarter campaign. All of a sudden this obstacle becomes an opportunity.

Has this experience made you more of an advocate for owning your own work as a filmmaker?

Jim Jarmusch wanted he and I to own the film. But at the time, I was just a guy who wanted to make good films, and thought that someone else was going to put them out and take care of the rest. That’s where my head was. In the Soup was such an education in how the industry we work in is so interconnected with publicity and promotion. It’s like musical chairs: there are a few films that are chosen. In the Soup is the same movie, whether he had made a deal with Miramax [after Sundance] or not. But it’s such a difference for [the fate] of the film.

One thing I’ve always admired about Quentin is that, right from the beginning, he was one of those guys who understood how to play the market. There’s only so much bandwidth to talk about a film, and if you don’t get in [the conversation] you may just be overlooked. When you get that opportunity, you’d better step up. I made a film recently called Little Feet that did very well critically. That’s the one people responded to the most since In the Soup, so I’m going to keep trying to do that. I wish I was personally wealthy so I could finance these movies, but it is what it is.

Kelly Reichardt and Oscilloscope Laboratories successfully launched a similar Kickstarter campaign in 2015 to restore her first feature, River of Grass. It seems like crowdfunding is increasingly a way to get film fans off the couch and involved in the art they love. Is that an exciting prospect for you as a filmmaker?

It’s really exciting. What’s really interesting [about crowdfunding] is that it empowers people. You don’t have to sit around and wait for someone else to decide what you see and how it gets seen. You become kind of a producer in it. And we need independent films. The whole idea [of indie cinema] got kind of twisted. No one’s ever tried to compete with Hollywood. There’s certain kinds of movies that need to be made, and don’t have as big an audience. Lenny Bruce didn’t have 10 billion people laughing at him, but he’s still an icon. You have to have specific stuff that not everyone’s going to get. Today, it’s very hard to get cutting edge films and new films that don’t have stars in them made. Something like Kickstarter makes it possible to find new ways of financing these movies.

Watch the trailer for the sepia-toned version of In the Soup below: